Water Quality and Closed Areas in Coastal Maine

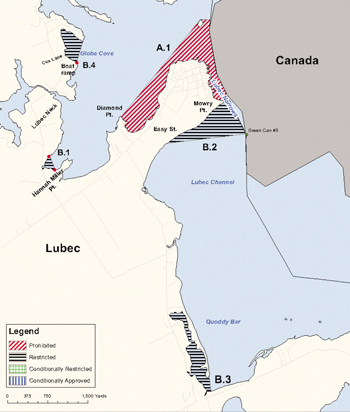

Lubec at the eastern border with Canada is much less developed than the Falmouth area. Yet the closures on this map are prohibited or restricted. Lubec Neck is not very populated. The tidal flow through Lubec Narrows can be expected to be very strong, but the area on both sides of the narrows are restricted. Lubec has a relatively low number of impervious surfaces, septic systems and parking lots. However, there are a couple of things about Lubec that are not revealed by a map. Lubec has seen a considerable population increase in the last decade or so. New residents in old houses may be overloading septic systems that are out of date or in need of repair. Lubec has three wastewater treatment plants and three outfalls (drainage pipes).There are eight wastewater treatment plants in the area. Various local factor include clustered septic systems, homes built on ledge and lots too small to have a septic system. All of these must use an alternative to wastewater treatment. That alternative in Lubec is a licensed discharge into the ocean via an outfall pipe. Credit: Maine DMR map

Water quality in coastal Maine is essential for maintaining marine habitat and protecting human health. Most publicity regarding water quality usually comes from summer red tide incidents. The Maine DMR closes an area to shellfishing until the threat has passed. Many of the people who hear about a red tide closure in the summer when it is more likely to occur may not be aware of what causes it, but know only to not eat shellfish from areas where ride tide has been detected.

Fecal coliform is another leading concern of water quality managers in Maine. The DMR and the Department of Health and Human Services are primarily focused on these two agents. Red tide is a toxin created by algae blooms in the water. Elevated water temperatures, wind direction and other factors determine whether this becomes a serious health threat to humans, usually in the summer months. Fecal coliform is bacteria from mammalian fecal waste. The sources include farms, woodlands, pets, septic systems, and water treatment plants.

The Maine DMR did not have figures for the number of shellfish areas closed every year or at any given time in a year. But the Maine DMR does 14,000 water tests for fecal coliform annually. The increasing scale and frequency of heavy rainfall is affecting the number of closures.

A lot of progress has been made over the last several decades in treating waste at treatment plants. But at the same time the incidence of algae blooms, red tide and fecal coliform alerts has become more common. The driver of this increase in the face of more public awareness of the problem is increasingly frequent heavy rainfall. Heavy rains overwhelm sewer systems, wastewater treatment plants, septic drainage fields and animal waste storage on farms, all of which create runoff that ends up in rivers, streams and ultimately coastal waters and estuaries.

In the ocean “all problems are coming from the land,” said Anamarija Frankic, a marine biologist at the University of Massachusetts in Boston.

“Getting control of fecal coliform has been going well,” said Mike Kuhns at the Maine EPA. Forty years ago point source was a major problem. Today, more is known about fecal coliform, and there are good controls in place. Less is known about non-point source pollutants, like chemicals, pharmaceuticals, micro beads and plastics as small as nano particles. “The biggest challenge,” said Kuhns, “is ocean acidity.”

State water quality standards are based on federal Clean Water Act standards. The states can make their water quality standards more stringent, but never less stringent. When the DMR locates, for example, a discharge pipe releasing waste into a cove, it goes to the state Environmental Protection Agency. If it is a clam flat, the flat is closed and water tests are done. The federal government delegates authority to the states in handling the management of the site and make funds available to the state for doing so.

Kohl Kanwit is lead water quality scientist at the Maine DMR. She said the DMR is focused on fecal coliform contamination. The fecal coliform that causes health hazards in water is the same in any warm-blooded animal—farm animals, wildlife, pets, and humans all have the harmful pathogens. When an area is closed it stays closed for 14 to 21 days. Kanwit said most people do not know where their wastewater goes or what happens at a wastewater treatment plant. The plants are expensive to build and operate and there is not a lot of money around to build more. They can be effective at treating water, she said, and they are operated by highly qualified staff.

The tests are expensive. The state simplifies the enormity of the problem by identifying the coliform vector that makes humans sick. Maine has a 3,500-mile-long coastline, the fourth largest in the nation after Alaska, Florida and Louisiana. The state does a shoreline survey every 12 years where the shoreline is walked to check septic tanks, beaver dams, ruptured septic pipes, etc. A “Problem Form” was developed to submit comments about what is found along the coast that needs to be addressed. When a problem is found then a problem form is left at the town’s Town Hall. From there it is sent to the landowner who has 30 days to respond to the Health and Human Services Department. If they do not, the problem form is sent to the local plumbing inspector.

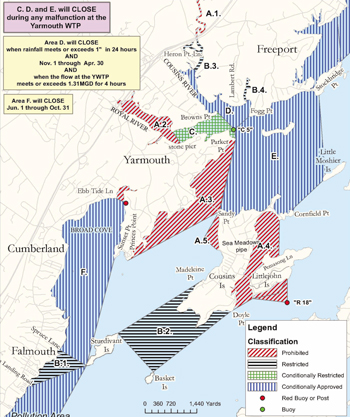

Royal River, Yarmouth, Maine 15 miles north of Portland on Casco Bay. Looking in a general way at two very different areas can illustrate some of the considerations in assessing the susceptibility to wastewater contamination and resultant area closures. The dark striped conditionally approved areas on this Falmouth area map may be so because they are open to tidal waters that clean the areas, but may also be subject to seasonal increased inputs to septic and wastewater systems. Seasonal storm water runoff could also effect this designation. The population is relatively high here, as is development. The Royal River has a generally sluggish water flow and that may contribute to its being designated prohibited. There are also a few boatyards in that area. There are a lot of parking lots, roofs, and roads in the area that would increase the impacts of storm water. There are likely wastewater treatment plants in the area as well. This complex of rivers, islands and dense coastal development also has estuaries that retain wastewater more than open coastline. The more open coastline sections are conditionally closed. Map by DMR

Kanwit said the impact any given volume of contaminants has on any particular site depends on many factors. One of the wild cards in water quality management has been increasingly common heavy rains. Heavy rains load pervious soils and wash more waste into waterways and waste treatment plants. Heavy storm water can overwhelm waste treatment plants and septic systems, releasing fecal coliform and other contaminants into the environment. Along the coast that means waste goes into coastal waters, coves and estuaries.

The number of areas in Maine closed to shellfishing as a result of contamination at any one time varies over the course of a year. Storm water is one notable factor. Others include the population in an area, the amount of impervious surfaces such as roads, roofs and parking lots, the influx of summer residents and the number boatyards, etc. Soil can absorb rain. Impervious surfaces create runoff that loads the soil with higher rates of water flow. Wastewater treatment plants often cannot handle the surges in runoff. Sewers can overflow with storm water and that water bypasses the system.

The complexity of the coves and estuaries the waste overflow runs into is a factor. If the area is not easily and often flushed by other rivers or daily tide, the problem lingers. In areas where the summer population increases significantly, the dog population increases and septic systems may be undersized or in need of maintenance. “Conditional closures” may be put in effect. Another conditional closure would apply where water quality being undermined could be predicted by the type and condition of a wastewater treatment plant, combined sewer and storm water flows and the past results of storm water surges.

Marine biotoxins are another water contaminant that is both less predictable and less controllable. Naturally occurring cyst phytoplankton live offshore and only when conditions are favorable, such as higher water temperatures, is a bloom created. Wind direction changes from storms can drive the bloom toward shore where shellfish consume large quantities of this single-cell plant which contains the toxin. The toxin does not affect the shellfish, but the concentration of the toxin in the shellfish can be deadly for humans who consume the shellfish.

Unlike fecal coliform that can be controlled, the arrival of and consumption by shellfish of bio-toxins in phytoplankton blooms cannot.

To the right and also on page 7 are two sample maps of closed areas created by the DMR.

Looking generally at two very different areas can illustrate some of the considerations in assessing the susceptibility to wastewater contamination and resultant area closures. The dark striped conditionally approved areas on this Falmouth area map may be so because they are open to tidal waters that clean the areas, but may also be subject to seasonal increased inputs to septic and wastewater systems. Seasonal storm water runoff could also effect this designation.

The population is relatively high here, as is development. The Royal River has a generally sluggish water flow and that may contribute to its being designated prohibited. There are also a few boatyards in that area. There are a lot of parking lots, roofs, and roads in the area that would increase the impacts of storm water. There are likely wastewater treatment plants in the area as well. This complex of rivers, islands and dense coastal development also has estuaries that retain wastewater more than open coastline. The more open coastline sections are conditionally closed.

DMR Closed Shellfish Area Maps: http://www.maine.gov/dmr/rm/public_health/closures/closedarea.htm