B A C K T H E N

Big Brig, Small Builder

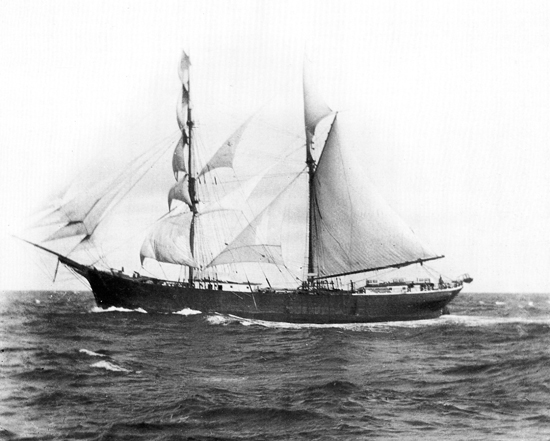

The monster half-brig H.B. Hussey, romping along before a quartering breeze with everything set. Built at Richmond in 1883 by T.J. Southard, who owned her as well, she was the only brig built in the nation that year, and among the last ever built. She was the last brig built on the Kennebec.

Sch. James Holmes and brig H.B. Hussey each made the run from Boston to Belfast last week inside of 24 hours. The brig arrived here Thursday night and the schooner Friday noon. The Hussey is loading ice at Pierce’s for Charleston, S.C. at 60 cents per ton. —The [Belfast] Republican Journal, Sept. 21, 1893.

In 1884, of perhaps 4,300 seagoing vessels under the American flag, only about 260 were the once-common brig. About 170 were built in Maine. The Hussey, at 545 tons, was among the twenty or so brigs measuring nearly 500 tons or more, led by the huge 622-ton C.C. Sweeney, built at Harrington in 1873. The Hussey, with a registered length of 160.6 feet, 36.2-foot beam, and 12.3-foot depth of hold, may have been the longest brig ever built. Four voyages of the Hussey—and one by the Jennie Hulburt, a 419-ton brig with similar depth of hold, built by Southard in 1880—noted in newspapers, were all made to southern ports. This may account for the brigs’ shoal drafts. By 1903 only about twenty American brigs survived, among them the Sweeney and the Hulburt. The Hussey had succumbed to heavy weather in February 1899, 160 miles off Montauk, while bound from Savannah to Portland. Her crew was picked up by the schooner Florence Leland.

The brig H.B. Hussey, at New York from Charlestown, carried away her foretopmast in a strong gale on the second, and the stick in falling away struck and killed Fred A. Dix of Deer Isle, Me. Such is a sailor’s fortune. –The [Bangor] Industrial Journal, Oct. 22, 1886.

Born in Boothbay in 1808, T.J. Southard, the Hussey’s builder, was a pint-sized dynamo. After a year at sea, he decided to learn about shipbuilding. He spent a year at joining, then three years black-smithing, three years in a machinist’s shop, one year in a rigging loft and at caulking, and six months learning drafting. At twenty-one he opened a blacksmith shop at Richmond, which village then consisted of but ten buildings. Southard would be the major factor in its growth. By 1836 he started building vessels, at first taking only a small share, and soon, building for his own account.

Southard was also Richmond’s first postmaster, a sherriff, kept both dry and West India goods stores, and owned an apothecary shop, two sawmills, a gristmill, and a mineral spring. He built wharves and a number of buildings. As a state representative and senator, he obtained charters for a state, a federal, and a savings bank. He established a cotton mill and a shoe factory. The elaborate opera house he built was ornamented by a life-sized statue of T.J. himself. Handling up to $1,800,000 a year, he never carried a memorandum book. In 1885 12,000 tons sailed under his famous anvil house flag.

In 1859 Southard ignited controversy by naming a ship Southern Rights. Supposedly the prescient Southard shrewdly (and correctly) calculated that this name would provide protection from Southern commerce raiders. (In 1883 Southard was part owner of a plantation in Mississippi, but it is not known whether this ownership preceded the War.)

In March 1883 it was noted in the press that the frame was being got out for Southard’s 103rd vessel, a 2,400-ton ship—the H.B. Hussey, having been launched that April, was thus the 102nd. (The ship’s frame, incidentally, was erected in but fifteen working days by but four men on the platform.) In Southard’s busiest year he was said to have built three ships and a schooner, and to have completed two ships which he had bought in frame. His final vessel—said to be number 111—was the four-masted schooner Edith L. Allen, built in 1890. Southard managed to find time to travel extensively in Europe, and to visit every state except Oregon. In May 1892 the Richmond Band serenaded the old man at his home, “in recognition of his long and useful life.” He died at age eighty-seven.

The other day T.J. Southard visited his farm ... where a number of men were at work in the hay field. Getting out of his carriage, the veteran borrowed a scythe ... and having tucked up his wristbands, braced himself on-his legs, and prepared to show the boys how to slaughter grass .... Mr. Southard swung the scythe at a lively rate and carried a swath as wide as a barn door. When he had concluded his experiment the field looked as though a cyclone had passed over it. Without saying a word the astonished farm hands picked up their tools and prepared to cut what little hay had been left standing, while their jovial employer—a man seventy-seven years of age—hopped into his carriage and drove rapidly away. –The Richmond Bee in The [Bangor] Industrial Journal, July 23, 1886.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Days Work, Part 1, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860–1920, Part II. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, 12 Starr St., Thomaston, Maine. 800-582-1899.