B O O K R E V I E W

A War Story That’s Not Over Yet

by Paul Molyneaux

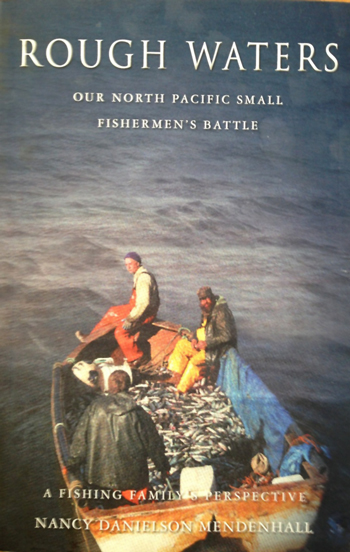

Rough Waters: Our North Pacific Small Fishermen’s Battle

By Nancy Danielson Mendenhall

Far Eastern Press, Seattle, 2015

In her book, Rough Waters: Our North Pacific Small Fishermen’s Battle, Nancy Danielson Mendenhall, who spent more than half a century in the Alaska salmon fishery, gives readers an intimate look at what small-scale fishermen have been up against in Alaska. In addition to her own experience, Mendenhall is heir to a family fishing legacy, and her book begins with stories that are personal and poignant. She describes how her family and their friends built their own boats and helped open up the commercial fisheries of the north. In addition to the commercial fisheries, she describes the importance of subsistence fisheries to Alaska and the role that fishing plays in both Native and non-Native Alaskan culture.

In the first part of her book, as Mendenhall writes with a depth of intimacy and understanding that transports the reader back to the 1960s, 70s and 80s, she hints at coming troubles. Dams, habitat destruction, increasing regulations, and competition from sport fishermen contribute to the “death by a thousand cuts” that many fishermen have experienced.

Fisheries are a vital part of Alaskan culture. Mendenhall notes that for most Americans, fisheries may occupy little more than a hazy corner of their consciousness. “It’s a different story in Alaska,” she writes, “where a recent poll found that 60% of the people still think that salmon is very important to the image of the state. Alaska is the only state that prioritizes subsistence fishing. People need to be able to get enough to eat and sell on a small scale, then commercial fishermen get their whack at the stocks, and after that, sports fishermen.”

Her stories are intimate and personal, revealing the values and cohesive spirit of the North Pacific fishing communities. But in the value system of the policy makers, things like intergenerational knowledge and cultural integrity cannot be measured in dollars, and so they are discounted.

Tolstoy once wrote that the history of battles is barely more than conjecture. Nobody knows really what the generals intended or how their orders were executed. Even those engaged in the fight have little awareness beyond the reach of their own vision. Mendenhall, after years of watching her friends and family struggle to stay in business, and many of them failing, finally recognized an institutional problem. “As I researched this book I discovered that although our federal government floods us with information promoting healthy, sustainable fisheries, its management is full of contradictions for the small fishermen, the majority…”

That’s putting it mildly, but in the second half of her book Mendenhall offers meticulously researched, and painfully detailed, analysis of how federal regulations have privatized fisheries and disenfranchised the small-scale fleet. Mendenhall’s play-by-play description of the North Pacific Fishery Management Council’s actions, from promoting Individual Transferable Quotas, to its unworkable programs ostensibly intended to protect small-scale fishermen and their rural communities. She writes that the council passed a Community Quota Entity (CQE) program, intended to buy quota from large operations and sell it to communities of less than 1,500 people. But most towns could not meet the costs. Mendenhall quotes Sven Haakanson: “It cost us two million to get that community quota working. Two million.” According to Mendenhall, Haakanson’s community, Old Harbor, was the only one out of 42 that really got the CQE working for it.

The battle Mendenhall chronicles takes place throughout the Alaska and North Pacific region over the course of a hundred years, but has been most fiercely fought in the last three decades. Mendenhall’s meticulous research shows how corporate interests have taken over the pollock and crab fisheries, and how quota management has shrunk the state’s halibut and black cod fleets with little or no conservation benefit, especially in Western Alaska where the pollock fleet is allowed to kill and discard thousands of salmon and halibut, much of it underreported.

Countering the gains made by the privatizers of Alaska’s fisheries, Mendenhall notes a number of fisheries that have endured due to one fortunate circumstance or another. As in any battle, survival is a matter of luck. But the gist of Mendenhall’s book is that the surviving small-scale fisheries are the kind that should be intentionally restored and preserved.

After a certain amount of time, war stories become completely defined by the winners, but as long as writers like Nancy Danielson Mendenhall exist, the voices of the underdogs will be heard. Rough Waters: Our North Pacific Small Fishermen’s Battle, is a war story, and the battle is not over yet.