Lessons Learned

Marine Accident Reports (UK)

Ann Backus, MS

One of the most instructive publications for fishermen is the Safety Digest published by the Marine Accident Investigation Branch in collaboration with the Department of Transport (DfT), located in Southampton, UK. The DfT website is https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-transport

The April 2016 issue of Safety Digest is titled “Lessons from Marine Accident Reports 1/2016.” Excerpts from this publication are permitted if properly cited, and it should be noted that the content is held under Crown Copyright 2016.

So what is in this issue of Safety Digest? The three main sections, Merchant Vessels, Fishing Vessels, and Recreational Craft, contain brief narratives of accidents and succinct discussions of lessons learned.

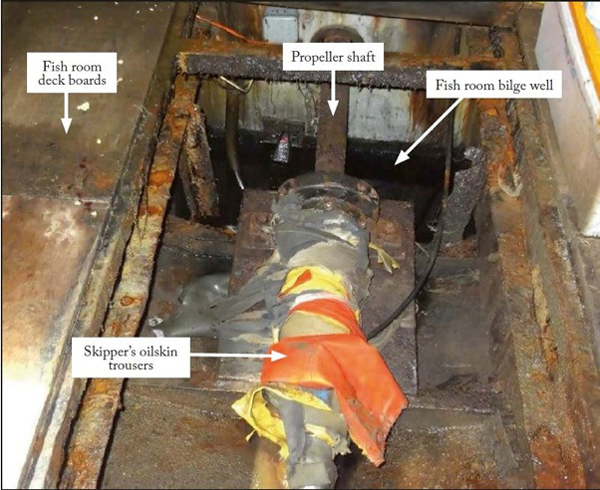

A skipper sailing alone slipped onto the rotating propeller shaft,

immediately entangling oilskins and his leg in the rotating shaft.

Let’s check-into the Fishing Vessel section: The first narrative titled “Making a Big Impression,” describes how Vessel B, while steaming to port after fishing, ran into Vessel A. In the case of Vessel B, the skipper’s view ahead was obscured by the radar display and B rammed into A’s bow. Vessel A, which had finished fishing, was in “not under command” mode and no one was in the wheelhouse keeping proper watch. The Lessons section cited two major infringements: 1) Skipper must have an unobstructed view; and 2) Someone must be in the wheelhouse at all times.

In the second narrative, “Don’t Get Carried Away,” a creel fisherman, fishing alone in a 9-meter boat, became entangled in the line after he tossed off a string of creels. He was pulled into the water, and was only able to swim to the surface when the line became slack after the first creel hit bottom. He grabbed a creel buoy to hang onto and waved another buoy to attract attention. He was rescued by a Samaritan fishing boat after about 35 minutes.

The situation is all too familiar to those of us on the East Coast: His boat was in gear and moving away from him; his Personal Flotation Device (PFD) and Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) were in the wheelhouse. Never mind that his boat, which was disappearing in the distance, was rescued later by another Samaritan who risked his own safety by jumping onto it. The uncertainty and anxiety of whether or not he, the lone fisherman, would be seen and rescued would have been alleviated had he been wearing his PFD and PLB.

The third narrative, “How Very Quickly Life Changes,” describes a lone skipper on a 10.8-meter steel beam trawler who noticed that his bilge pump in the well near the propeller shaft had tripped out. He descended into the hold, removed the boards above the well and was preparing to diagnose his pump problem when he presumably “slipped or stepped” onto the rotating propeller shaft – immediately entangling oilskins and his leg in the rotating shaft. “The skipper managed to cut himself free and, although very badly injured, was able to make his way out of the fish hold to the wheelhouse.” This sounds promising on the face of it, but because of his injury he could not reach his VHF radio which was “mounted in a bracket suspended from the wheelhouse roof, and was out of reach of the severely injured skipper.” Fortunately he was within range of a land-based cell tower (not always the case on the water) and was able to call for help. This incident cost him his leg and an extended period of rehabilitation.

The Lessons section for this narrative points out the necessity of disengaging any motorized equipment or components before working near them. It cites the hazards of fishing alone and suggests that fishermen have Personal Locator Beacons and perhaps, even if not required, an installed and working Automatic Identification System (AIS) which is a marine tracking system used worldwide.

The fourth narrative “Lone Working” is an extremely sad account of a lone fisherman on a scallop dredger who was pulled into the “warping drum of a winch” presumably when his clothing was caught in the turning drum. He was fatally injured. As we have found in our study of drum winches in the northwestern Atlantic, many of the winches on our trawlers and dredges are not guarded and not outfitted with safety shut-off devices. The lessons here are again about the hazards of fishing alone, the importance of good maintenance and of not fishing on retrofitted boats where the retrofit is not carefully done and not appropriate for lone fishing.

I’ll leave you to read the other two narratives “Lost in the Fog” (Case 21 p. 50) and “Supper Would Have Been on Time if the Vessel Had Not Sunk” (Case 22, p 52) which are available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/

file/512603/MAIBSafetyDigest1_16.pdf.

In summary, these accident narratives are not unusual in the sense that situations such as lone fishing, unguarded equipment, unoccupied wheelhouses, obstructed views, poorly maintained or poorly designed gear and PFDs sitting idle are readily observable within our fishing industry in the U.S. We appreciate the efforts of the Marine Accident Investigation Branch in the UK to bring these accident cases onto our radar where we can learn from them and perhaps avert an injury or a fatality by taking more precaution.

Citation: Marine Accident Investigation Branch. “Lessons from Marine Accident Reports 1/2016.” Safety Digest. Crown Copyright 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/

512603/MAIBSafetyDigest1_16.pdf

Ann Backus, MS is an Instructor in Occupational Health at Harvard School of Public Health, 665 Huntington Ave., Boston MA 02115, 617-432-3327, abackus@hohp.harvard.edu.