Schooner Racing

by Mike Crowe

Driven hard, with the rail buried, a man could get washed overboard down on the lee side hauling the headsail sheets. Capt. Joseph Collins, fisherman, historian, and Maine man noted before a formal race had been considered, that “so fear-less and ardent are the fishermen that the better judgement of the skipper is frequently overcome by the solicitations of the crew, and in the hope of outstripping some rival vessel, sail is carried in unreasonable excess. It is not uncommon for some of the more headstrong of the skippers to carry so much sail on their vessels that the lee rail is completely under water most of the time.” (New Bedford Whaling Museum)

Originally published in the Fishermen’s Voice in 1999.

Men went on schooners to fish the banks gambling on a better trip than the last. They also went for many other reasons – debt, marriage problems, comradeship, and for reasons they couldn’t explain as well as for the hell of it.

Sterling Hayden, native Mainer, schooner fisherman, race participant and actor wrote, “Fishermen knew what it was like to bust their guts and haul their hearts out… then maybe hang to the vessel’s wheel and ease her as she roared to-ward home and mother with her rail dragging the water, the salt spray rattling like machine-gun fire off whatever canvas might be drawing her back up under the lee of the land.”

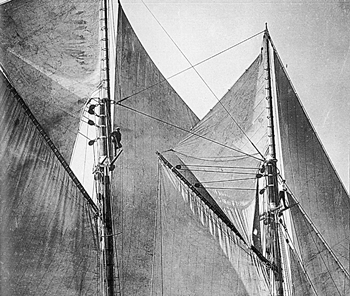

A crewman’s view of the boat from a position on the bowsprit where head sails were set. The bowsprit regularly plunged through swells. Men were often washed off leading it to be known as the widowmaker. Later schooners eliminated the bow-sprit by having the bow extended to a point where the sprit would have ended. They were known as Indian Headers, and all given Indian names. (Cape Ann Historical Assoc.)

A fast cruise back from the banks often meant piling on all the canvas. Setting and changing sail combinations with the eight sails schooners typically carried required a high level of skill. Tricks also might come into play. “Dirty tricks, like secretly shifting ballast, disingenuous fouls such as letting out a main boom to damage the rigging on a nearby leeward ves-sel, conveniently unnoticed mark buoys, and midnight switching of suits of sails were not uncharacteristic of the fishermen for whom a practical joke was the finest kind and yachtsmen’s etiquette pure baloney.”

Fishermen worked weeks or months on the banks filling a schooner. They might work long stretches of very long days, either being reason enough to want to return to port quickly.

The Onata, fishing bound around 1905. At 106', she was fast for her size, regularly logging 13 knots. (Cape Ann Historical Assoc.)

Fishermen had long raced against either each other. They also raced just to get back fast after the boat was filled.

The first organized race among fishing schooners was in 1886. According to William Hale, who wrote The Race It Blew in 1892, the only genuine organized race between regular working fishing vessels, sailed by regular working fisher-men was the one he describes in his book.

Whether racing to market or against a rival boat, speed and weather compounded the difficulty, complexity and danger. Climbing into the rigging with the hull heeled over and riding up, over and down swells would up the ante. Verbal communications were dampened by the wind howling through the rigging. The language aboard ship has been attributed by some, in part, to the noise levels at times. Soft sounds, syllables and words that are not heard above the roar are dropped.

Sterling Hayden has described the skill and unique experience of these sailors. “Their everyday task was to catch fish, but their niche in maritime history is due in no small part to their incomparable ability to battle to windward in the teeth of living gales. To say nothing of their capacity to heave to and ride out some of the most daunting weather and infuri-ate conditions to be found rampaging around on the surface of the Seven Seas.”

Mastheadmen perched like birds. The mastheadman unfurls the topsails so they can be set by the halyards from the deck. The foremastheadman also carries the tack and clew of the fore topsail up and over the main top mast stay (between the masts) when the boat comes about on the other tack. It was this stay that Sterling Hayden was noted for crossing hand over hand to cover fore and main positions. With a stiff breeze and a sea running required nerves of steel and near perfect preci-sion on deck and aloft. (Cape Ann Historical Assoc.)

Full set of typical schooner sails. Varying combinations varied performance. (Cape Ann Historical Assoc.)