The Famous Schooner Polly

by Tom Seymour

The 61' Polly tied up in a river, possibly the upper Passagassawakeag River, Belfast, in this undated photo. Likely later in life by the looks of her topsides. Registered in Belfast, Polly was active in Belfast and Rockland. Penobscot Marine Museum photo.

The famed schooner Polly met her inglorious fate on a sad day in 1918 in Quincy, Massachusetts. The Polly had a near-reprieve when the Daughters of the American Revolution attempted to purchase her and transform her into a marine museum. But that transaction was never consummated and instead the salt-impregnated white oak from the ancient ship went up in flames in woodstoves and fireplaces.

The Polly was launched in Amesbury, Massachusetts in 1806 in the shipyard of Richard Currier. Constructed of long-lasting and durable white oak, Polly was of 48 tons burden with a 61-foot waterline length. She drew 5 feet of water forward and 7 feet aft when unloaded. Polly served as a packet, sailing from Boston to Portland and also, points at the mouth of the Penobscot River. She also saw service as a fishing vessel and as such, her insides became filled with salt. The introduction of salt preserved the wood and helped an already strong and well-built vessel become even stronger. The Polly’s fishing days ended when the War of 1812 intervened and Polly became a privateer.

Her service as a privateer was notable in that the Polly captured a total of 11 prizes. And for that, The National Society of The United States Daughters of 1812, State of New York, placed a bronze tablet honoring her wartime service on the outside forward end of her cabin-house on November 2, 1910.

Rock-Solid

As a privateer

the Polly captured a

total of 11 prizes.

The reason for the Polly’s longevity lies in the materials used to build her. Built during an age with first-growth timber was still available for all types of construction, beams in the Polly were up to four times as massive as those used a century hence. Also, American pride showed through in her construction. Builders at that time were esteemed craftsmen who took the utmost pride and care in their work. Thus, high-quality engineering, done with the best available materials, served the schooner well.

During the great “Gale of 1897,” when shipping suffered greatly, along with a terrible loss of life, Polly proved her mettle. Captain McFarland, one of her owners, gave an account of how Polly weathered the great storm: “In the fall of 1897 she was caught out in the bay, in the great southwester that caused such havoc to our shipping, many of the big three- and four-masters getting terribly handled. The Polly was loaded with three hundred hogsheads of salt, a heavy and dead cargo, but she came through the worst of it, and never parted a rope yarn.”

In addition to her rock-solid construction, Polly owned another distinction. Her style of build, with her high-pooped stern and rounded bows illustrated for the first time a purely American style of construction.

Polly Transformed

The Polly began service as a sloop and then sometime around 1850, was made into a schooner. This transformation occurred when she was repaired and rebuilt by Jonathan Tinker at Tinker’s Shipyard on Tinker’s Island, just off of Mount Desert Island. The rebuilt sloop was again repaired by Captain Ephraim Pray at Mount Desert.

But even the mightiest must eventually fall and on April 26, 1874, Polly went ashore during a late-winter storm at Owl’s Head, Maine. Then, as a testimony to her continuing soundness, Captain Lewis A. Arey purchased her on the spot. Captain Arey had the vessel re-floated and used her in the lumber trade until 1885, when she was again repaired and rebuilt, whereupon she re-entered commercial service as a lime-freighter.

The Polly again went ashore in December, 1890 (some accounts list this as 1889), at Fort McClary at Kittery Point, Maine. Her captain, L.A. Snow of Rockland nearly perished during the event. This time, though, the grounding was immortalized on canvas. Marine painter George S. Wasson of Kittery Point, documented the Polly’s rescue in his now well-known painting. This wasn’t the only time that Polly was the subject of a painting. Percy Sanborn, a noted Belfast area artist of the latter part of the 19th century, portrayed Polly as she sailed past “The Monument,” a light on Steele’s Ledge at the entrance to Belfast Harbor. The painting was recently sold to a private individual at an auction in Thomaston. Other artists, too, chose Polly as a subject. Among these were F.W. Dillingham and Walter L. Dean, painter of the White Squadron.

In another nautical mishap that occurred on November 29, 1902, Polly went hard aground at Owl’s Head when her skipper, Chandler Farr, brought her to shore for calking and painting on an outflowing tide. The tide left her high and dry, but the vessel was re-floated and continued on in commercial service.

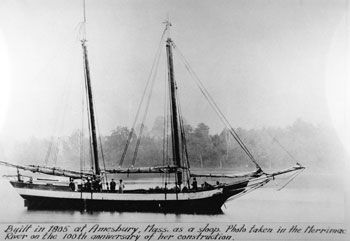

Polly, 1904

Penobscot Marine Museum photo.

A photo of the Polly under full sail appeared in an article in the Belfast, Maine newspaper, The Republican Journal, on March, 1904. At that time she was the oldest American Merchant Marine vessel still under commission. The vessel was then in her winter quarters at the Swan & Sibley dock in Belfast, having spent the previous season variously as a Boston packet and a bay-coaster.

By 1904, Polly had exceeded the expected lifespan of similar vessels twice over. And yet she was still in more-than serviceable condition. It was reported then that much of the original frame, timbers and planks from when she went into commercial service in 1805 were still in evidence and still sound as when the vessel was built. Also, one of the vessel’s original anchors suspended from the cat-head. Some of her original outfit and furniture remained aboard in full view.

As of 1904, Polly still had 14 years of service remaining. That same year, Polly figured prominently in an Old Home Week festival held in the place where she was built, Amesbury, Massachusetts. Records indicate that the vessel was the centerpiece of the week-long celebration. And that was when the bronze plaque, highlighted at the beginning of this article, was dedicated.

The United States Navy was on hand for the event, with naval officers in attendance as well as a military band from Brooklyn Navy Yard. Additionally, a granddaughter of one of Polly’s commanders from the War of 1812, accompanied by an old logbook that attested to the authenticity of her relation to that commander, acted as sponsor by unveiling the plaque.

An account of the ceremony included the following: “Thus in preserving and memorializing the Polly, we are doing honor to those early builders who, though classified as artisans, were animated with the true spirit of the fine arts. It was their handiwork of which this little vessel is the sole survivor, that was destined soon to make our merchant fleet the marvel of the world.”

The reason for the

Polly’s longevity lies

in the materials used

to build her.

The Polly’s accolades were many. Among these was her speed. She was the fleetest of all in her class. The Polly’s speed record was only surpassed when Gloucester fishing vessels made their appearance. Even then, the newer-style vessels had a hard time to best the Polly. A sloop yacht, Mariette, built along the Gloucester fishing vessel lines, thought to outpace Polly during a run from Camden to Belfast on a southwest wind. The challenger eventually gained ascendency, but not without lots of effort and perhaps even a little luck. Even in the early 20th century, the century-old Polly was a force to be reckoned with.

By 1910, Polly was still in excellent shape and at age 105 was still in operation. Then J. H. Weldon purchased the vessel from Captain Walter V. Spencer of Rockland as a pleasure craft.

Little is known of the Polly’s adventures from just after the War of 1812 through 1840, the year she entered the coasting trade. Then, the 60-foot sailing vessel began making the dangerous trip around Cape Horn. She did this six times with no serious incidents. The little vessel then sailed around the world, not once, but twice.

At last the old warrior faced her end. Several period luminaries, including Admiral Perry, considered purchasing the vessel, but that didn’t happen. Despite her indescribable value as an American icon, Polly was doomed to oblivion. She was unceremoniously dismantled and sold for firewood, a sad and ignominious end to one of America’s premier sailing vessels. Were this to have occurred in 2018 rather than 1918, things would most certainly have gone in a different direction.

Today, even though Polly is long gone, we still have the records of her service, as well as the paintings by period artists. With these we can still read and see enough to gain some understanding of the merit, worth and long and faithful service of a gone but not forgotten bit of American history, the Polly.