Maine Residents vs Acadian Canada

The Controversial Other Weed

The Maine plaintiffs

want to know, do they or

does the public have the

rights to attached rockweed.

A case that has been in the Maine courts for the last year is currently in the discovery stage, according to the plaintiffs’ attorney Gordon Smith at Verrill Dana, in Portland. The Maine plaintiffs, Carl and Ken Ross of Pembroke and the Roque Island Gardiner Homestead near Jonesport, are asking for summary judgment on the question of whether rockweed is privately owned in Maine. The defendant is Acadian Sea Plants Ltd., Halifax, NS Canada.

The complaint stems from the harvest of rockweed from the plaintiffs’ coastal property. This is a dispute over ownership rights in the intertidal zone. In Maine, unlike in most other states, the landowner owns to the low water mark. The right to take shellfish and worms is settled law. But is there a right to take rockweed? Rights in Maine’s intertidal zone have a long, history with roots in Massachusetts colonial law. The rights have been clear up to the point of the seaweed harvest that started around 1999-2000.

The Maine plaintiffs are looking for a definitive solution to the question: do they or does the public have the rights to attached rockweed on property that has been in the Ross family for 100 years, and since colonial days for the Gardiner Homestead.

Public trust rights are referred to as the right to “fishing, fowling and navigation,” all of which have been stretched, warped and redefined over the centuries as the so-called Public Trust Law has evolved.

Whether any of these intertidal or riparian rights are exclusive was never stated in the original 1641 legal document, said Smith. It is expected Acadian Sea Plants will argue that taking seaweed is fishing. The last time the court addressed the issue of intertidal rights was in McGarvey v. Whittredge, 2011. The justices then were split 3 to 3, the seventh being absent, on whether the use of scuba gear in the intertidal zone was in the public trust doctrine because walking with scuba gear across the intertidal zone could be construed to be “navigating” the intertidal zone. Three of the justices considered this a “tortured reading” of the law.

While property rights cases in the intertidal zone make the evening news if they are about beach access in southern Maine, fewer members of the public today know about the increased harvesting of rockweed. The harvesting has led some landowners to ask, If the rockweed is worth money, why am I not getting paid anything for it, not even stumpage? If I have rights in the intertidal zone, why can I not influence the harvest of marine life there?

As environmental issues have made their way to the nation’s front pages, questions have arisen about what is going on in the front windows of Maine coastal homes. Seaweed? It’s a weed, it’s just there, always has been. Now, informed residents want to know what seaweed does for the marine environment.

Some coastal residents have more recently begun asking why a Canadian company is taking Maine seaweed. Marine scientists in the U.S. and Canada have published papers describing rockweed as critical habitat for many of the commercial species Maine fishing communities rely on. Lobster, and finfish (cod, pollock, herring, flounder etc) and shellfish are a few marine organisms that spend parts of their lives in rockweed or are protected by rockweed. The Gulf of Maine Council, a group of U.S. and Canadian scientists, list the top 100 most important species in the Gulf of Maine. Rockweed was ranked number 4, above salmon and lobster.

Areas of the Canadian Maritimes have seen their rockweed over-harvested. Scientists say it’s time to reconsider the role rockweed plays in the coastal environment and how this resource is being managed.

Beal thinks the minimum

16" stem rule and the

maximum 17% biomass

take limit are adequate

to preserve biomass.

Robin Hadlock Seeley is a scientist who has researched and written about rockweed for many years. Seeley is a 8th-generation Mainer, and Cornell University research scientist. She’s as deep into rockweed as anyone looking closely at coastal Maine today. Seeley knows rockweed serves as habitat for key commercial species in Maine because, as she has said, she has literally been up to her knees in it since she was a child.

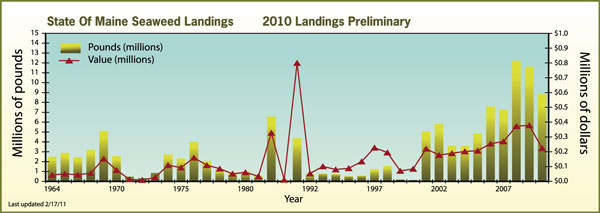

The landed value of seaweed, or price paid at the dock, is relatively low. The majority is processed into wholesale and retail products such as fertilizer, soil conditioner, animal feed supplements and nutritional food and health items for human consumption. Statewide rockweed landings for 2010 were 12.7 million pounds, having a landed value of $253,525. The 2010 Cobscook Bay rockweed harvest totaled 106,313 pounds with a landed value of $2,126. (Source: DMR. 2010)

A full version of a 2012 peer-reviewed scientific journal paper by Seeley and Dr. William Schlesinger on the rockweed that lines the Maine coast, is available at fishermensvoice.com. An abstract follows here:

ABSTRACT—Seeley

Burgeoning global demand for products derived from seaweeds is driving the increased removal of wild coastal seaweed biomass, an emerging low trophic level industry. These products are marketed as organic and “sustainable.” Brown macroalgae, such as kelps (Laminariales) and rockweeds (Fucales), are foundational species that form underwater forests and thus support a diverse vertebrate, invertebrate, and algal community—including important commercial species—and deliver organic matter to coastal ecosystems. The measure of sustainability used by the rockweed (Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) LeJolis) industry, maximum sustainable yield, accounts for neither rockweed’s role as habitat for 150+ species, including species of commercial or conservation significance, nor its role in coastal and estuarine ecosystems. To determine whether rockweed cutting is “sustainable” will require data on the long-term and ecosystem-wide impacts of cutting rockweed. Once a sustainable level of cutting is determined, strict regulation by resource managers will be required to protect rockweed habitat. Until sustainable levels of cutting and appropriate regulations are identified, commercial-scale rockweed cutting presents a risk to coastal ecosystems and the human communities that depend on those ecosystems.

Brian Beal, a marine biologist at the University of Maine/Machias said, “Anywhere from 30% to 60% of the rockweed biomass, depending on the area considered, can be lost to storm damage and to snails that chew on the stems making them more susceptible to storms. Some of this rockweed sloughs off and is replaced with new growth.” Beal was on the plan development team (PDT) of the rockweed working group that developed the rockweed management plan with the Maine DMR in 2014. The PDT, said Beal, discussed rising demand for rockweed from international markets and new technology to mechanically cut the plants. Beal thinks the minimum 16" stem rule and the maximum 17% biomass take limit are adequate sustainability measures to preserve biomass.

One harvest regulatory measure is the 16" height of the rockweed plant that is supposed to be left between where it is attached to rock, the holdfast, and where it has been cut off for harvest. The rockweed frond can grow to 6 feet in length. Hand-harvester Larch Hanson of Gouldsboro has harvested the same area for 40 years. Hanson leaves a length above the holdfast of 36" rather than the state mandated 16", to preserve habitat function.

Beal said he considers increased complaints about rockweed harvests and intertidal rights as the difference between preservation and conservation. “Some complainants want to preserve – cut nothing and leave it alone, and others want to conserve – manage it for human consumption,” said Beal. Seeley said, “the science is there, we know a lot about the important ecological services that rockweed provides in life and after it breaks down, and this supports the need for an ecosystem-based assessment and management of the resource”

Some communities have been assured that the DMR is watching the rockweed harvest. At the same time, the DMR is said to have no funding to support inspections of the rockweed landings to inspect whether holdfasts are being removed and how much bycatch comes out of the water with the weed.

Maine seaweed landings have increased from about 500,000 pounds in 1995 to about 17 million pounds in 2015 – a fold increase. About 90-95% of that is rockweed. Once hand-harvested with cutter rakes on long wooden handles by harvesters leaning out of small boats, the industry is going to mechanized cutters. These increasethe ease of removing tons of rockweed biomass, but their accuracy in maintaining the 16" holdfast length has been questioned. See video of mechanized rockweed cutter: fishermensvoice.com.

While the question of who owns the rockweed and who has a right to harvest it works its way through the Maine courts the larger and likely more important questions revolve around how much of these plants should be removed, and how often. Or whether it is such an important habitat for commercial species that we are better off just leaving it in the water. The lawsuit will eventually deliver the final answer regarding who owns the rockweed, but science will have to determine rockweed’s true ecosystem value.

Below is an excerpt from the updated August 2016 “Public Shoreline Access in Maine: A Citizen’s Guide to Ocean and Coastal Law.” The complete version can be seen at fishermensvoice.com.

The balance of interests in the intertidal area: fishing, fowling, and navigating

The phrase “fishing, fowling and navigation” comes from Maine’s history and laws regarding the intertidal area. The references to fishing, fowling, and navigation can be found in the Colonial Ordinances of the 1640s that governed the colony of Massachusetts and the district of Maine before they became states.2 Those terms have been interpreted by courts in the ensuing centuries. Maine and Massachusetts are exceptional in their approach to the intertidal zone. In most states, private owners hold title to the high-water mark and the states hold the intertidal zone, submerged lands, and coastal waters as trustees for the benefit of the public. This is known as the “Public Trust Doctrine,” a legal principle that dates back centuries to English law (and ancient Roman law before that) and was a protection against those, including kings and emperors, who might impede the public’s interests in important activities such as fishing, commerce, and navigation. The Public Trust Doctrine is a common law principle that supports the public’s right of coastal access for certain coastal-dependent activities. While the Public Trust Doctrine has certain elements that apply to all states (i.e., the state holds certain legal interests in the coastal area for the benefit of its citizens), each state has developed and applied the Public Trust Doctrine in accordance with its property law and historical background. At the same time, the public may acquire coastal access rights in a variety of other forms, such as an easement.3 While these concepts and terms may seem like legal technicalities and jargon, their impact on public access is something everyone who has an interest in the coast can understand, especially when the issues are illustrated by some recent legal cases. Since the benefits and the operation of the Public Trust Doctrine strongly parallel the way the Colonial Ordinance works in Maine, some refer to the Colonial Ordinance as part of Maine’s variation of the Public Trust Doctrine.Maine legislators and judges sometimes use the names of the rules interchangeably. The background and history of both the Public Trust Doctrine in Maine and the Colonial Ordinance of 1647 are extensively set out in the 1989 decision Bell v. Town of Wells (“Moody Beach”), as well as in the 2011 McGarvey v. Whittredge case.

More on rockweed at http://www.acsf.cornell.edu/news/blog/sustainable-seaweed. Also, there is a live link to the above Blog, R.H.Seeley’s and W. Schlesinger’s rockweed paper and the Public Shoreline Access in Maine documents at fishermensvoice.com.