75 Knots

Nicholas Walsh, PA

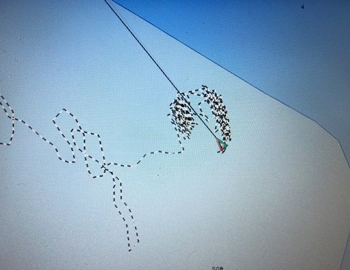

A snapshot from the chart plotter showing where we anchored and dragged. With the engine’s help we managed to slow our dragging, tacking across the wind instead of heading straight downwind. The Danforth held, but then for an awful moment dragged again before catching, as seen here.

Last month, we were in the Dismal Swamp Canal headed south, bound for Florida and the Bahamas. We entered Pamlico Sound, very beautiful vistas across huge marshes bordered by Cape Hatteras, and headed for Belville, North Carolina. Hurricane Michael was making landfall on the Florida panhandle, and was forecast to cross our area as a tropical storm. We needed shelter from the storm.

Slade Creek sounded good, a marshy creek about a half-mile wide, with little enough fetch that we’d be fully protected from big waves. We anchored in ten feet and put out a hundred feet of chain on a shock-absorbing bridle. The chart said the bottom was “soft” but I figured our big spade type anchor would do the job. I considered linking a Danforth to the spade, in line, but didn’t want to give up our only spare anchor. (I’ve since bought a third.)

Winds were forecasted at 50-60 knots. There was occasional mention of hurricane winds, which I tried not to hear. We stripped the canvas off the boat, lashed everything down tight, and settled in for our hurricane party.

Through the day all went well. Winds got up to 45 or so and it was exciting. The anchor and bridal were performing perfectly. I was even prepared to be a little disappointed – my first big winds on board, you know.

Around ten that evening the wind suddenly came west and began to gust, to 60, 70, 75 knots. About then our anchor alarm sounded. We were dragging.

My plan for dragging was to power into the wind, to relieve strain on the anchor. It didn’t work – my little diesel couldn’t begin to get the bow into the wind. The anchor was still trying to hold, but we were headed for the flats, about a quarter of a mile away now.

In those conditions

you need to get

almost everything right.

I didn’t veer more chain because I had a nylon bridle on and I didn’t want to play with windlass in such violent winds. I realize now I just should have let out all the chain, to hell with the bridle, and jury-rigged something to take the shock of the chain. Instead, we let go the ready anchor, a 35 pound Danforth, on a nylon rode, and to my surprise it held. We were maybe 100 feet from shoal water. Wow.

The high winds lasted about 90 minutes, during which time I continued to use the engine. Ellen was brilliant and so brave, manning the bow in the roaring storm, heavy rain and occasional green water, and giving a blast on her whistle if I was in danger of overrunning the nylon. She went to bed when the gusts dropped to a placid 40-45 but I stayed awake until dawn, unwilling to lose the boat because I went to bed too soon. The morning was sunny, blue sky and a light wind, as if the whole thing had been a dream. It still seems that way to me.

I did a lot of things right and some things wrong, and in those conditions you need to get almost everything right. A lesson learned was to treat any storm forecast with caution. In good weather forecasts are usually right on, but storms are highly dynamic and exact forecasting is impossible. In the same situation, I would let out all my chain from the start – that excess chain was doing me no good in the chain locker, and chain in mud is said to act as a powerful anchor in itself. Also, a spade type anchor doesn’t work well in soft bottom. Better a Danforth or the aluminum Fortress type, which many experienced boaters use down that way. The chart plotter was a blessing, letting me see exactly where we were, where we were heading and, if we didn’t stop, how long it would take us to wreck.

But we survived and so did the boat. Moorehead City, and an anchoring basin dredged in Camp Lejeune, the Marine Corps base. We were awakened there by two giant hovercraft, the Corps’ preferred method of storming a beach. Offshore from Winyah Inlet to Charleston, where we spent 16 days visiting with friends.

Every day brought

its moment of

high drama.

Charleston is a wealthy city and the wealth was built on slaves. Owners of the city mansions had four or five rice or indigo plantations outside of town, with slaves numbering in the thousands. A few generations later the wealth is still there, same families and all. Things I learned: Some slaves were owned by freed slaves. Sometimes the “manumitted” ex-slaves bought slaves to free them, but more often they bought them as property. Various punishment contractors existed in town, ready to take your surly house slave and return him or her a few days later, whipped or worked into submission. The city itself was repelled by some aspects of slavery as much as it depended on it. Open air slave auctions were banned early on, but slavery continued until the South’s defeat in 1865, decades after it was illegal in most of the civilized world. (England outlawed slavery in 1833.) As the civil war approached slaves became more difficult to control, and there were a number of violent rebellions. The white population was terrified of insurrection.

We skipped Georgia, going offshore, but entered at the St. Mary’s River on the Florida border. There we revisited Cumberland Island, a fantastic 20,000 acre national seashore, once a Carnegie hunting retreat. Wild horses and abundant wildlife are among the attractions. Go if you can.

Then we motored down the “Ditch” to St. Augustine and points south. Folks use the Intracoastal Waterway as an alternative to going offshore, and it certainly is useful, but day after day on the ICW is no picnic. You are generally in a narrow dredged channel, and it’s easy to run aground. There’s lots of traffic, both commercial and recreational, and there are bridges. Some of the bridges we could motor under with our 48-foot mast, but others are drawbridges. There is more current than you’d expect – we saw 5 knots against us passing under one bridge. Every day brought its moment of high drama.

In short, the ICW is one fairly stressy day after another, and you can only do about 50 miles a day. The first thing we did when we stopped the engine was make a stiff drink. My wife claimed the ICW was making an alcoholic of her.

Soon enough we were in Vero Beach, Florida, where our son lives. We hauled the boat in nearby Fort Pierce, and flew home for Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Stay out of trouble.

Nicholas Walsh is an admiralty lawyer practicing in Portland. He may be reached at 772-2191, or nwalsh@gwi.net.