The Suicide Run to Murmansk

by Tom Seymour

In the first joint British-American convoy under British command, the PQ-17 Convoy sailed from Hvalfjord, Iceland for Russia, on June 27, 1942. German forces located the convoy on July 1 and followed the convoy. German U-boats and Luftwaffe airplanes attacked sinking 24 of the 35 ships. Fourteen of the ships were American merchants. The surviving convoy ships became scattered in the Arctic. Official U.S. Navy photograph.

During the opening days of World War II, when Allied nation Russia was under attack from Nazi Germany, it became plain to the other Allied nations that, were Russia to capitulate, then Britain would be next. And after that, the natural succession of events was unthinkable.

Russia was unable to import food or munitions because of German interference. Not only was the Soviet Union ill-prepared to fight Nazi Germany on anything like an equal footing, people were starving from lack of food. And so beginning in August 1941 and continuing through May 1945, groups of merchant ships formed convoys that sailed to arctic Russia from North America, Iceland and the United Kingdom.

The convoys sailed both the Atlantic and Arctic oceans to two northern port cities on the arctic on Russia’s west coast of the Soviet Union, namely Arkhangelsk and Murmansk. A total of 78 convoys made the treacherous crossing to these fiercely cold outposts. It was said, and with some degree of accuracy, that few men made it twice through the Murmansk run and lived. Thus the name, “The Suicide Run To Murmansk.”

PQ-17 Arctic Convoy, June-July 1942. Torpedoing a barrage balloon carrying steamship, by a German U-boat, during the battle of PQ-17, North of Norway. Photographed from the submarine. Official U.S. Navy photograph.

The supplies sent to the Soviets were courtesy of the American Lend-Lease program. In March 1941 the Roosevelt administration inaugurated the “Lend-Lease” program, sending to Britain, Russia, China, and other Allied nations vast amounts of war materials to use in self-defense against Germany and Japan. The U.S. had not yet entered the war and this was one way for it to contribute to the allied efforts. In all, the United States sent 15,000 aircraft, 7,000 tanks and 350,000 tons of explosives to the Soviet Union. In addition to this, 15,000,000 pairs of American-made boots reached the Russians. These were of vital importance to those fighting on the Eastern Front during the unusually severe winters.

It was readily acknowledged that it was impossible that unescorted conveys would have even a ghost of a chance against German air and sea power, so convoys were accompanied by ships of the U.S. Navy, Royal Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy. But despite this degree of protection, 85 merchant vessels, along with 16 warships of the Royal Navy, were lost in the Murmannsk convoys. The U.S Congress had authorized the use of Navy guns and Navy gunners on merchant ships.

Danger didn’t diminish upon reaching Murmansk, since the battle front was only 18 miles away. With the enemy so close, it was easy for the German Luftwaffe to attack the port and the city on a regular basis. It didn’t take long before the City of Murmansk was a charred ruin, with burned-out houses and chimneys marking where people once lived and worked. These were the conditions that navy gunners and merchant mariners were faced with.

Heroic Mariners

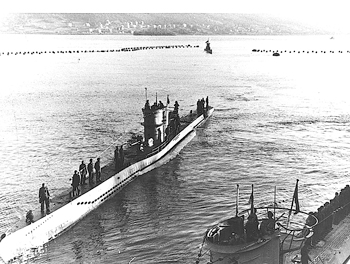

U-boat crews aboard their craft, at Narvik, Norway, following the action against PQ-17. Boats are type VIIC. The one at right is U-251 (timm). German wartime photographs.

The men who took part in these relief runs to Russia faced harrowing conditions. German planes and submarines and sometimes warships, constantly plagued the convoys. Those whose vessels were sunk by enemy fire faced certain death in the icy waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans. It took immense courage and determination to volunteer for these missions.

One such merchant mariner, Captain Peter J. MacPherson, of Ullapool, Skye, Scotland, was among the heroes of the Murmansk runs. Captain MacPherson made multiple crossings from Scotland to Murmansk and one thing that kept him going in the face of certain death was an incident that occurred during one of the early crossings.

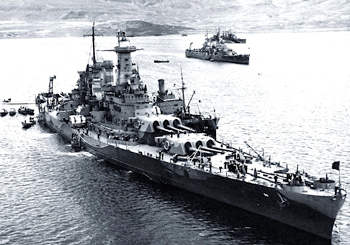

The covering forces of the PQ-17 Convoy in the foreground. Official U.S. Navy photograph.

Captain MacPherson was on the bridge when German planes strafed the deck of his ship. A young girl, the daughter of an officer, was on deck, enjoying the sunny day. Captain MacPherson told the author, “I watched, stunned, as the Germans raked the deck with gunfire, ripping the little girl to shreds. I vividly remember her dress, a red-and-white, checked calico dress. It was all spread out on the deck. In the end, not much was left of the little girl or her dress.”

“From that point on,” MacPherson said, “I determined to fight the Germans with every inch of my being. And in every action the picture of that little girl and her red-checkered dress always came to mind.”

Captain MacPherson was not injured during his time on the various Murmansk runs, but he had several close scrapes with death. One of these occurred when the vessel next to him was torpedoed by a German submarine. The vessel Captain MacPherson was on made it through unscathed.

Years after this incident, Captain MacPherson, who had since become a U.S. citizen, living in Northport, Maine, was watching the Highland games in Brunswick, Maine, when he struck up a conversation with Warren Blake, of Jefferson, Maine. The two men were casual acquaintances, but neither was aware that they once were in the same convoy. The author overheard this conversation and was spellbound when the two began talking of the Murmansk run. As it turned out, Captain MacPherson’s vessel was on one side of the stricken ship, while Warren Blake’s ship was on the other side. After that, Blake and MacPherson became fast friends.

The covering forces of the PQ-17 Convoy in the foreground. Official U.S. Navy photograph.

The convoys and the supplies they carried helped Russia to stay in the war. Moreover, the convoys were instrumental in helping the allies to all-out victory against Nazi Germany. Since then, books have been written and movies made about the valiant efforts of those merchant mariners and navy gunners of the Murmansk Suicide Run.

Years passed, but the heroes of the Murmansk Run were not forgotten, least of all by the Soviets. The Piskarevskoya Memorial Cemetery in Leningrad carries a plaque with the legend, “No one has been forgotten…nothing has been forgotten.” This was in reference to the heroes of the convoys that saved Russia during the late war.

Dedication Ceremonies

An inscription in a cemetery was not the end of the tributes paid by the Russians to the survivors of the Murmansk Suicide Runs. Five hundred veterans of the runs were decorated in two different ceremonies in 1992, held, respectively, in Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, DC.

Captain Peter MacPherson was invited to the ceremony at Baltimore. Preparing for his trip, Captain MacPherson remarked how excited he was at the prospect of being decorated by Russian head of state, Mikhail Gorbachev. Those were the days when, “Gorby” was a popular figure worldwide.

Captain MacPherson arrived at the Baltimore ceremony only to find that Mr. Gorbachev was unable to attend and instead, had sent Mr. Viktor Volkov, Chief of the Russian Consulate, in his place. Taking it all in stride, Captain MacPherson graciously accepted his decoration from Mr. Volkov.

In addition to the decorations, the Liberty Ship S/S John W. Brown was moored next to the site. The addition of a Liberty Ship* was especially meaningful, since many similar Liberty Ships participated in the Murmansk runs, carrying cargo to the beleaguered Russians.

Besides the Liberty Ship were two perfectly restored, World War II-era Jeeps. Also, a number of the veterans participating wore military uniforms of the period.

After an invocation and a moving speech by the ambassador of the Russian Federation, the veterans were each called by name to come to the front of the gathering, where they were each awarded a medal, a handshake and a thank-you.

After the last veteran was recognized and given his decoration, the group moved outdoors, where Mr. Volkov gave a vodka toast to those lost at sea and also, to the continuing friendship between the Russian people and the citizens of the United States. At the completion of the toast, the John W. Brown was open to those present. This not only gave the veterans an opportunity to re-live their times aboard such ships, it also gave their families a closer look at the kind of vessels their loved ones sailed in during the Suicide Runs to Murmansk.

Back home after the event, Captain MacPherson shared an amusing anecdote with the author. “They gave a vodka toast, but there was barely enough vodka to wet the bottom. Luckily, a number of others who didn’t drink poured their vodka into my glass, so in the end I was able to toast with a respectable shot of vodka.”

Captain MacPherson also commented that his new home in coastal Maine was the closest place he had ever seen to his native Skye. Captain Peter J. MacPherson died on July 14, 2006, at age 90.

*Liberty Ships were built by the U.S. government, operated as merchant ships and manned by merchant marines with U.S. Navy armed support aboard. The John W. Brown, was named after Canadian born American labor union leader John W. Brown (1867-1941). It was built in Baltimore, Maryland. Laid down on July 28, 1942 and launched on September 07, 1942. It is one of two remaining operational Liberty Ships. More than 400 of these Liberty Ships were built at the New England Ship Building Corporation shipyard in South Portland, Maine between 1941 and 1945.