Popham Colony – The Other Jamestown

by Tom Seymour

Model of the replica of the Virginia being built by the Maine’s First Ship group in Bath, Maine. The original Virginia was built in 1609 at the Popham Colony in what is now Phippsburg, Maine. The first English-built ship in Maine and possibly in all the English colonies of North America. Maine’s First Shop photo.

It was the year 1606 and England’s king James 1 was convinced that the time had come to colonize Virginia. At that time, all of America’s east coast, from Florida to the Canadian Maritimes, was referred to as, “Virginia.”

To that end the English monarch granted a charter to a group called “The Virginia Company.” This included the “London Company” and the “Plymouth Company.” Thus, a consortium of private individuals and investors was financially enabled to sail to the new world to establish two colonies, Jamestown, in Virginia, and the Popham Colony at the mouth of the Kennebec River in Maine.

The two companies were rivals from the beginning. The king and his advisors had planned it that way, reasoning that since the goal of colonization was financial gain from the forests and waters of North America, the two companies would work harder than if only one group had a monopoly.

And to further inspire the new colonists to prosper, a neutral ground was set aside somewhere in between the two proposed colonies. Either company was free to colonize and develop the neutral ground. All they needed was the intent and the ability to do so.

Popham Colony was founded by the Plymouth Company, a group that, under the King’s charter, was entitled to lands along the Atlantic coast between 34 degrees and 45 degrees N. The rival London Company had a grant for lands between 34 degrees and 41 degrees N.

Weymouth’s heavy-handed dealings with the Indians

were not forgotten by

the original inhabitants.

The London Company fared better than the Plymouth Company from the very beginning. While The London Company experienced no difficulties in reaching their appointed destination and establishing Jamestown on May 4, 1607. But the Plymouth Company’s vessel, Richard, which left England in August of 1606, was captured by the Spanish in the waters off Florida in November of that year.

The Plymouth Company’s second attempt met with success. Two vessels, Gift of God and Mary and John, made it to the Midcoast region of what is now the State of Maine, shortly after the London Company’s founding of Jamestown.

The Plymouth Company’s vessels held about 120 persons between them. These were former soldiers, merhants, farmers, traders and carpenters. Nobleman George Popham, aboard the Gift of God, accompanied the group as their leader. Also among the number was the author’s ancestor, Reverend Richard Seymour. The Mary and John was commanded by Captain Raleigh Gilbert.

Full-size replica of the Virginia is being built on the Kennebec at the Bath Freight Shed, 27 Commercial Street, Bath, Maine. The 50' ship is being built with traditional methods. Virginia Project DBA Maine’s First Ship photo.

Before setting foot on the mainland, the vessels, according to A Brief History of Maine, George J. Varney, 1890, the vessels stopped first at Monhegan Island, where they found a cross erected several years earlier by Captain John Weymouth, an Englishman who had explored Midcoast Maine. Weymouth’s heavy-handed dealings with the Indians were not forgotten by the original inhabitants. Weymouth had captured several Indians and took them back to England. Among the passengers on Mary and John, was Skidwarroes, one of the Indians that Weymouth had captured and who was released to return to his home.

Before leaving Monhegan Island, the companies of both ships, according to A Brief History of Maine, had a religious service, with Richard Seymour preaching the first sermon ever delivered in New England.

Indian Troubles

Next, Skidwarroes guided the company to Pemaquid, now the Town of Bristol. The a group from Gilbert’s vessel disembarked and proceded to an Indian village, where they met armed resistance, a result of Captain Weymouth’s troubled legacy. The settlers returned to ship. The English tried again, unsuccessfully, to make contact with the natives, who were distrustful and slipped away into the woods, taking Skidwarroes with them.

Leaving Pemaquid, the vessels finally reached the mouth of the Sagadahoc, which was the name given to the Kennebec at the time. Here they landed and began the search for a suitable site on which to begin building. But first, the Plymouth Company had given the group a sealed package, to be opened upon reaching their destination. Opening the package, they found that George Popham was their president and Captain Raleigh Gilbert was their admiral. Also included in the package were written copies of the laws they were meant to follow, along with list of all officers.

The Virginia consisted of

all native lumber, but out

of necessity also included

ironwork and sails brought

from England.

The group wasted no time in building a fort, a storehouse and dwellings. Also, since part of the group’s mission was to prove that North America could supply all the materials needed to build sailing ships, Master Builder Digby, a London carpenter, set about building a 30-ton pinnace called, Virginia. When completed, Virginia consisted of all native lumber, but out of necessity also included ironwork and sails brought from England.

Meanwhile, while the new community was taking shape, Captain Gilbert and crew began exploring the coast, sailing south to Casco Bay. Returning, Gilbert sailed up the Kennebec River, where he tried to initiate trade with the Indians. But, according to A Brief History of Maine, the furs the Indians offered were of such poor quality that Gilbert refused to trade with them. This precipitated a dangerous situation and the settlers considered themselves fortunate to escape without a bloody fight.

Trouble Looms

Back at the settlement, things progressed rapidly and by the onset of winter, the colonists had finished a storehouse, one large dwelling and a number of small cottages. Also, they had completed their fort, which they named Fort St. George, in honor of their president, George Popham. Despite these gains, that autumn saw about half of the company returning to England. Their decision may have been prophetic, because when the Maine Winter hit in full force, those left behind fared poorly.

Popham Colony represents

the only English colony in

the Americas to have a

documented plan.

Their dwellings were insufficient to keep out the bitter cold and a fire in the storehouse resulted in the loss of many provisions. Besides that, sickness rendered many unfit for duty. It was a miserable winter, but surprisingly, only one person died, their president, George Popham. This left Captain Gilbert as the new leader of the colonists.

It was George Popham who had, earlier, sent a letter to King James 1 via the two vessels that returned to the mother country in late fall of 1607. In the letter, Popham wrote, “The natives constantly affirm that in these parts there are nutmegs, mace and cinnamon…with many other products of great value and importance.” Either Popham was uninformed or the Indians were feeding him false information in order to satisfy his wants, because neither cinnamon nor mace were native to America’s shores.

Coin recovered at the Popham archeological dig site. Virginia Project DBA Maine’s First Ship photo.

When the two vessels returned from England the following spring, they bore the news that Captain Gilbert’s brother had died and Gilbert, as his heir, was entitled to the estate. Gilbert decided to leave the newly established Popham Colony and return to England to claim his inheritance.

So given the death of their president and now the coming loss of their leader, the remaining colonists decided to give up the venture and return to England. Some of the colonists returned to England with Captain Gilbert, while others sailed on Virginia, south to Jamestown.

Thus ended the ill-fated Popham Colony. But its untimely abandonment, though difficult at the time, has given modern-day historians a trove of information on how life was lived in the early 17th century.

As time passed, the Popham Colony was forgotten. Little by little, signs of the colony dwindled, obscure, overwhelmed, but not forgotten. In 1624, Samuel Maverick, a visitor to what was once Popham Colony remarked, “I found Rootes and Garden hearbs and some old walles there,…which shewed it to be the place where they had been.”

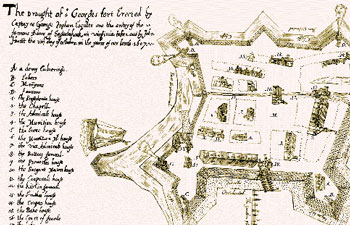

The Map

Among other superlatives, Popham Colony represents the only English colony in the Americas to have a documented plan, in the form of a map. At the time of the Popham Colony, Spain had eyes on the North America and even conducted some limited forms of espionage. One item, a map of Popham Colony, compiled and drawn by Englishman John Hunt, clandestinely made its way to Spain’s King Philip III, in 1608.

In later years, the Hunt Map became key to the discovery of the exact site of the old Popham Colony. The map shows a star-shaped fort, along with 25 (one contemporary source gives this number as 50) different buildings. Much of the map, though, was highly stylized and modern historians questioned its veracity. But the Hunt Map was all anyone had to go on. And on that basis, according to Athena Review Vol. III, Wendell S. Hadlock began excavating the site, with the first excavation taking place in 1962 and the second in 1964.

Early sketch of proposed Fort George by Hunt. Virginia project DBA Maine’s First Ship graphic.

However, Hadlock’s findings were inconclusive. The expected stone foundations were never located. The only artifacts uncovered were several pot sherds from North Devonshire. These, however, could not be dated with any certainty.

And so the Popham Colony lay, as it had for so long, out of sight and out of mind. But all that was to change. In 1990, according to the Athena Review story, archaeologist Dr. Jeffrey P. Brian of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, was visiting a friend in Maine. While there, Brian noticed a marker at a historic site that mentioned the Popham Colony. His interest piqued, Brian wondered if tangible proof of the colony was present.

Returning to Maine in 1993 Brian and a colleague walked Sabino Head, the supposed site of the old colony. In a history-changing moment, it was clearly seen that the shape of the land neatly corresponded with the John Hunt map. Hunt knew that this could provide a snapshot of the genesis of English settlement in North America. Then in 1994, Brian dug the first test pit and the evidence was encouraging. After that his team worked diligently and after seven weeks of digging, they found evidence of a 70-cm-diameter post hole. The hole was filled with the rotted remains of a pine post. This sufficed to convince Brian that he had at long last located a storehouse post hole and with it, Fort George.

At Sabino Head, the

supposed site of

the old colony, the

shape of the land neatly

corresponded with the

John Hunt map.

After this, Dr. Brian spent two years analyzing his past findings. They were encouraging enough to support further field work, so Brian returned to the site and it was then that he found proof positive of his suspicions. Brian had already made an accurate contour map of the site and then determined that by rotating the Hunt Map 20 degrees east of magnetic north, both maps made a precise fit. This positively verified the accuracy of the Hunt Map.

In 1997, armed with his new information, Brian began excavating along the newly established lines and this time his team located a line of post holes set 9 ½ feet apart. After this things quickly fell into place, with the discovery of burned sills between the posts, structural timbers and fired clay.

Then, according to the Athena Review article, everything came together. The team uncovered remnants of the base ends of the original posts, along with hundreds of artifacts that included glass beads, bits of broken bottles, armor, nails, lead projectiles and even a clay pipe and notably, a calking iron, the type used in ship construction. This iron was likely used in building the Virginia.

Dr. Brian’s work has at last determined the site of the Popham Colony and also, where various structures stood. However, parts of the fort lie on private property and the landowners are unwilling to permit further excavation. Work at the site ended in 2005. A public park sits on part of the site.

Today we have a unique opportunity to visit one of the earliest settlements in New England, a contemporary of the Jamestown Colony but situated right here on the Maine coast. This should rate as a must-see for anyone interested in not only Maine history but also the history of early America.