The Mysterious Case of the Mary Celeste

by Tom Seymour

Mary Celeste was found abandoned, the lifeboat missing, binnacle broken with the glass shattered, the sextant gone, captain, family and crew nowhere to be found.

The sailing vessel Mary Celeste was the center of a 19th-century mystery that was the equal of modern-day cases of alien abduction and Bermuda Triangle losses of ships and planes.

The scene of action, though, was nowhere near the Bermuda Triangle but rather, somewhere off the Straits of Gibraltar. And while both contemporary and modern sources note this as a case of ship abandonment, no one knows for sure what happened. The underlying question, then, is did those on board abandon the vessel on purpose for some unknown reason or were they taken off against their wills, victims of foul play, either by pirates or mutineers? Or was it something else entirely?

On December 4, 1872, Mary Celeste was found abandoned, the lifeboat missing, binnacle (a glass-topped box which houses the ship’s compass) broken with the glass shattered, the sextant gone, captain, family and crew nowhere to be found and the ship’s papers and captain’s personal belongings, minus his sword, vanished.

The vessel, when located, was under sail, but just barely. Later, after being towed into Gibraltar, the Admiralty Court found what appeared to be blood stains on the deck and on the captain’s sword. But further investigation proved the substance was not blood. What it was remains undetermined.

Bad Luck

The Mary Celeste, a brigantine, was built on Spencer’s Island, Nova Scotia, in 1860 and launched under British registry in 1861 under the name Amazon. In preparation for her maiden voyage in June of 1861, the ship loaded a cargo of timber bound for London. But her captain, Captain McLellan, was suddenly taken sick shortly afterward and on June 19, died.

John Nutting Parker assumed captain’s duties and so, finally, the Amazon set sail for London. But in what proved a precursor to future unhappy events, Amazon had a serious collision with fishing gear off of Eastport, Maine. Finally, after unloading in London, Amazon collided with a brig in the English Channel. The brig sunk as a result of the collision.

Later, in 1863, Captain Parker was succeeded by William Thompson, who commanded the vessel for four years, during which nothing of particular notice occurred. But then, in October of 1867, Amazon was blown ashore on Cape Breton Island, Canada, where she suffered damage to the point that her owners declared her a wreck. Then, on October 15, Alexander McBean of Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, purchased the vessel as a derelict.

McBean soon divested himself of his new acquisition and sold the damaged vessel to another Nova Scotian who, in turn, sold it to Richard W. Haines, an American, who spent $8,825 to restore the vessel. Haines, a mariner, captained the rebuilt vessel himself and registered her in New York as the Mary Celeste.

But Haines was in serious debt and his creditors seized the ship, which was in turn, sold to a consortium of New York investors. Then, in 1872, the vessel was refitted to the tune of $10,000. Her length, breadth and depth were increased and a new deck added. In addition, a number of unsatisfactory timbers were replaced. All in all, the Mary Celeste became an entirely new ship, capable of hauling considerably more cargo than in her previous incarnation.

Then, the vessels’ new captain, Benjamin Spooner Briggs, purchased a share of the vessel. Some sources say this was two-fifths, others, a considerably lesser amount.

Captain Briggs

Benjamin Spooner Briggs, of Massachusetts, spent his career at sea. Known as a fair and honorable man, his crews always had the greatest respect for him. Able and hard-working, Captain Briggs was the epitome of politeness and decorum. A devout man, Briggs eschewed all forms of alcoholic drink. Benjamin Briggs was the last man that anyone ever imagined would reside at the center of an unsavory and even now, unexplained controversy.

In 1871, Briggs, along with his brother, another mariner, had decided to quit the sea and begin a hardware business together in New Bedford. But that decision was short-lived when Benjamin changed his mind and purchased his share in the Mary Celeste.

Captain Briggs then modified the vessel, adding a cabin so that his family could accompany him on a trip to Genoa, Italy. Briggs’s son, Arthur, remained home in Massachusetts, staying with his grandmother in order to continue his education.

While Mary Celeste lay in New York Harbor, another brigantine, Dei Gratia, a Canadian vessel, sat at anchor in Hoboken, New Jersey, a nearby port. The Dei Gratia, too, was bound for Genoa, Italy by way of Gibraltar. Captain David Morehouse, a contemporary of Captain Briggs, is thought to have had an acquaintance with Captain Briggs. And like Captain Briggs, Captain Morehouse was well-known and well-respected by mariners of his day.

Captain Briggs, his family and crew set out from Staten Island New York in 1872, loaded with a cargo of toxic, denatured alcohol. This was the last instance that anyone ever saw any of them alive. Eight days later, Dei Gratia set sail for Gibraltar, following a course similar to that of Mary Celeste.

Ghost Ship

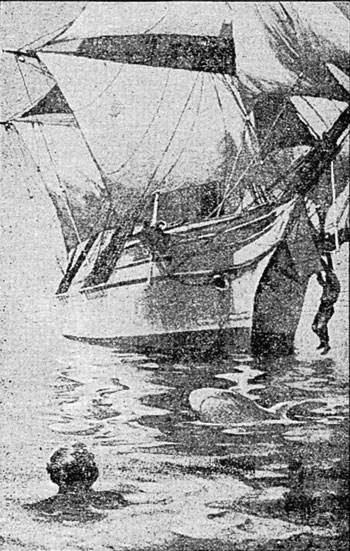

Painting of the Mary Celeste as Amazon 1861 under sail and the British flag.

This much is known about the disposition of the Mary Celeste and that is, the vessel successfully completed the trip across the Atlantic. But after that, the case falls into oblivion, speculation and controversy.

On December 4, 1872, Dei Gratia was about halfway between the Azores and Portugal when, at 1 p.m., the helmsman spied a vessel about 6 miles off, heading toward Dei Gratia. The new vessel acted erratically and as it drew closer it became clear that her sails were set in an odd manner.

This raised Captain Morehouse’s suspicions. When the distance between the two vessels became fairly close, Captain Morehouse sent first mate Oliver Deveau and second mate John Wright off in the ship’s boat to determine the cause of the other vessel’s odd behavior. It was quickly established that the mysterious vessel was the Mary Celeste. Hailing the vessel drew no answer so Deveau and Wright boarded the ship.

There, they found a bizarre scene. Sails were tattered, with some missing altogether. Rigging was likewise damaged. Ropes hung over the ship’s sides. The main hatch was tightly covered, but the fore and lazarette hatches were open, with their covers nearby, on the deck. The hold contained about 3 ½ feet of water, somewhat more than might normally be found.

The ship’s log, which was located in the mate’s cabin, showed a date of 8:00 a.m., November 25. It showed the Mary Celeste’s position at that time to be off Santa Maria Island in the Azores, a nautical distance of 400 miles from her present position.

The cabin interiors showed signs of water damage, but the galley was neat and trim, with provisions and equipment tidily stored away. However, the scene didn’t suggest any violence, save for something like blood (which, as mentioned earlier, proved not to be blood) on the deck and captain’s sword. For all appearances, the entire human population of Mary Celeste had simply boarded the ship’s boat and left for parts unknown.

Final Disposition

Upon hearing the mate’s report, Captain Morehouse determined to sail the derelict vessel to Gibraltar, there to claim salvage rights. The captain split his crew and both vessels, desperately undermanned, limped the 600 nautical miles to Gibraltar, where he intended to claim salvage rights. Once at Gibraltar the Mary Celeste was impounded by the Vice Admiralty Court in preparation for salvage hearings.

At the hearing, testimony from mates Deveau and Wright was misconstrued to suggest that foul play was at the bottom of the ship’s plight. Fredrick Solly Flood, Attorney General of Gibraltar, concluded that the crew, having broken into the ship’s cargo of denatured alcohol and having become drunk, murdered the captain, his family and crew and then left the ship via the ship’s boat. Flood also inferred that Captain Morehouse and his mates were not acting in good faith and were concealing pertinent information.

But none of that could be proved. Also, attorney Flood hadn’t taken into consideration the nature of the alcohol on board. Denatured alcohol is not drinkable and is, in fact, toxic. Had the crew become drunk on it, they would surely have suffered extreme physical repercussions, possibly death.

His suspicions unsupported, Flood released Mary Celeste on February 25 and within two weeks a local crew, captained by George Blatchford, another Massachusetts sea captain, sailed for Genoa. Then on April 8, Captain Morehouse’s salvage payment was decided. He was awarded 1,700 British pounds, only 1/5 the value of the vessel and her cargo.

This was an extremely low award considering the difficulty and hazards involved in bringing Mary Celeste to port. The court criticized Captain Morehouse for allowing his first mate to deliver its cargo of petroleum during the ongoing proceedings. Morehouse, however, remained in Gibraltar throughout the hearing. Nonetheless, this criticism would cloud Morehouse’s and his crew’s reputation for the remainder of his days.

The case was later tried in the worldwide court of public opinion and every solution from piracy, mutiny, attack by a giant squid, supernatural intercession and natural disasters such as waterspouts were offered. However, nothing fully explained away the strange case of the doomed Mary Celeste.

Final Indignity

Undated or location photo of the Mary Celeste. Stacks on steam powered vessels in the background may indicate the photo was taken in the later years of its troubled life.

The consortium sold Mary Celeste to a group of New York businessmen at a great loss. The vessel then went on to service in the West Indian and Indian Ocean trade, where she did nothing but lose money. Then, in February 1879, the vessel was reported to have called upon the island of St. Helena, where she sought a doctor to treat seriously ill Captain Tuthill. But medical attention was of no avail and Captain Tuthill died on the island, the third captain of Mary Celeste to die unexpectedly. This had the effect of fortifying the notion that the vessel was cursed.

Then, in February 1880, her owners sold Mary Celeste to a group of Boston businessmen. Her new captain, Thomas L. Fleming, held his position until August, 1884, when the new owners replaced him with Captain Gilman C. Parker. Then in November of that year, Captain Parker entered into a conspiracy with some Boston shippers to load the vessel with mostly useless and worthless cargo, which they insured to the tune of $30,000, a princely sum in those days.

On January 3, 1885, the captain ran the vessel onto the Rochelois Bank, a well-known and well-mapped coral reef. The vessel’s bottom was demolished, making her unfit for repair. Captain and crew then rowed the ship’s boat to shore, where the captain filed insurance claims on the highly-insured cargo. The captain also sold $500 worth of salvageable cargo to the American Consul.

However, the counsel later reported that the cargo he had purchased was nearly worthless and this prompted an insurance investigation. Captain Parker and the Boston shippers were charged with the crime of willfully casting away the ship, known at that time as, “barratry,” a crime that carried the death penalty.

However, in another unusual twist of fate, the judge finagled an agreement by which the defendants would withdraw their insurance claim and pay back all monies they had received. Captain Parker’s barratry charge was set aside and he left, a free man.

But Captain Parker’s reputation was irreparably destroyed and he died three months later, broken and penniless. A co-defendant soon went insane and another committed suicide. It seemed that the cursed ship had extracted her full amount of human suffering and torment. To this day, the full account of the abandonment of Mary Celeste remains a mystery.