California fish dragger. |

A five-year stock rebuilding program was implemented in 1994, with the goal of reducing fishing effort by 50 percent. Limits on the number of vessels in the fishery were imposed, as was the amount of time many vessels could spend at sea. More rigorous controls were imposed in 1996, which led to economic hardship in fishing communities and subsequent financial assistance programs.

The number of potential days at sea remained a concern, however; of the 154,286 allocated in 1998, only 51,880 were reported as being used. “There are many reasons that permitted multispecies effort goes unused,” NMFS writes in a supplementary notice. “Vessels may be working in other fisheries. Market conditions (including fish prices, fuel, labor, maintenance, lost opportunity costs and other variables) may not make participation in the multispecies fisheries sufficiently profitable. Vessels may be in need of repair or otherwise inoperable. Adverse weather may prevent or discourage use of days at sea.

“If the multispecies fish stocks begin to recover,” the notice says, “or market incentives prompt inactive or less than fully active permittees to initiate or to increase their effort in the fishery, then the fishery resource rebuilding program may not achieve its goals.” The majority of boats of 45 feet or less that are active are having trouble remaining profitable, Terrill said. More than 70 percent of the smaller-boat fleet, 50 feet or less, haven’t been using their permits. This compares with larger boats above 50 feet, which have a 27 percent latency rate.

But listeners pointed out that the permanent revocation of permits would punish those who held off fishing because stocks were down. People said that NMFS should buy out the big boats first. At the same time, one man said, the program should provide a decent price to the fisherman who does want to sell his permit, because it represents a lifetime of potential earnings that are no longer obtainable.

Terrill asked for input on how to rank bids. He said there has been some discussion of ranking them based on vessel capacity, using factors such as length and horsepower as indicators. A ranking system is needed, he said, because more than $10 million in bids might come in.

Flat fees were also under consideration. For example, a $25,000 fee would remove 400 permits; $100,000 would remove 100. One man noted that the permit is worthless financially now. “Until I either die or get done,” he said, “because (the federal government) won’t let you break the permit up – short of selling it back to the government – it’s got zero value.”

Even a fee of $100,000, said another, doesn’t amount to anything if the fish come back and a guy has lost his permit. Others were more concerned with the program’s larger implications. “We’re more concerned about our region losing its fishing rights,” said James Houghton of Bar Harbor. “Ultimately, it’s driving the small boats out, and that’s what Down East is…What we’re going to end up with is no fishery. We don’t have a fishery now. That’s why there’s latency. In effect,” Houghton said, “you’re screwing eastern Maine.”

Houghton said the model being presented doesn’t make sense; the haul of a small boat doesn’t come anywhere close to that of a 100-footer. Stonington Fisheries Alliance member and former Department of Marine Resources commissioner Robin Alden said that taking away the permit is a recipe for disaster for Maine.

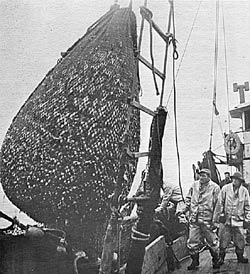

Load of fish off Georges Bank. |

Maine has the highest percentage of latent permits in the small-boat category, Alden said, and most fishermen go after lobster these days. Historically, the state has depended on mixed fisheries. “Diversity is incredibly important,” Alden said. Being able to hold on to permits until stocks come back gives fishermen potential for the future, she said. “I suggest that you could buy a lot of permits and you won’t reduce capacity,” Alden said.

“The device you’re using to calculate fishing power is a joke,” said Ted Ames, Alden’s husband and an industry activist. “You’re only consolidating fishing in the hands of a few. You need to use a realistic measure,” Ames said, “if you’re going to compare fishing power.” An 85-foot boat can stay at sea 10 to 14 days and can ice some 250,000 to 350,000 pounds of fish. “That’s where your fishing power is.”

Groundfishing has been a traditional part of Maine’s multi-fishery practices and economy for centuries, Ames said. “To buy a permit from a lobster fisherman who groundfishes three or four months a year is the closest thing to a joke…Taking our access to those fish is the closest thing to robbery because we’re not the problem and we never were.

“If you want to get at capacity,” Ames said, “go for capacity.” At one point, he said, Maine had about 1,200 groundfish boats, mostly small. Now there are about 150 active permits in Maine, almost all in Portland.

“This process is putting Maine out of the groundfish business and removing an important piece of the coastal economy,” Ames said. The program would only result in robbing the small boats and handing the fishery to large vessels, he said. “This isn’t going to pass the smell test at all,” Ames said.

Alden said that, because groundfishing hasn’t been good for 15 years or so, the program may well work out fine for the older fisherman who is just as happy to make some money off his permit. “But for the future of the fishing communities of Maine,” Alden said, “it’s tragic.”

Alden said the plan is coming at “a terrible, terrible time” because of current uncertainty as the New England Fisheries Management Council finalizes new measures – potentially including days-at-sea and area closure modifications, and sector allocations such as inshore gillnetting and offshore dragging – to control the industry, through Amendment 13 to the Northeast Multispecies Plan.

Alden suggested the program be put on hold until Amendment 13 comes through and people can see whether they have the right to fish at all. Ames suggested an alternative approach, to buy back permits at a fair price from people who want to sell them, but then place the permits, with reasonable restrictions, in a pool for the future use of Down East communities which traditionally groundfish.

“The bottom line is, if you remove the permits and dispose of them, you will have eliminated Maine’s fleet,” Ames said. Terrill said the broader discussion is outside the limits of the plan, which is required to go forward. The public comment period closed May 25; a final plan will be developed in the summer.

|