|

Why?

The DMR points to over-fishing. The fishermen are blaming the scientists and regulators for not protecting the resource. The livelihood of 742 of Maine’s fishermen is on the line, and many of those men and women have just one word on their lips, “Why?”

Speaking at the beginning of the forum meeting, Dr. Rick Wahle a DMR scientist and expert on urchin biomass, told the crowd that the Maine urchin population may be on the verge of irretrievable collapse, particularly in Zone 1. His presentation compared results from six marine protected areas (where no fishing has been allowed) to six control areas, during a three-year study. Wahle concluded that urchin populations can withstand landings or depletion down to a certain “threshold,” at which point they can not replenish themselves.

“Where exactly this threshold is, is subject to debate,” Wahle said. “But it’s pretty clear the threshold exists and we’ve exceeded it in many areas.”

Dr. Larry Harris is a zoology professor from the University of New Hampshire. He’s also an expert on urchins and has been active with the Maine Sea Urchin Zone Council. Harris said that from his personal experience, he has no doubt that the urchin stocks are as bad as the DMR stock assessments claim they are. But he’s much more optimistic that both Zones 2 and 1 could sustain at least limited fisheries next season.

“You don’t want to close the fishery down totally, because you want to keep the infrastructure in place,” Harris said. “It’s much easier to struggle along at an anorexic level for awhile and maintain at least some people in the industry, so that when it does start to come back, it can grow slowly.”

There were a lot of questions asked and some heated debate during the Urchin seminar at the Fishermen’s Forum March 4-6 at the Samoset in Rockland. |

Harris suggests drastically cutting back Zone 1, at least for a year, to try and see if some aspect of the industry infrastructure can remain in place and at least some people can try to make some money. “I think that there probably are some pockets of urchins in Zone 1,” Harris said. “I don’t think that they’re all gone. There is some recruitment, they are settling on the bottom and trying to grow. If we can sort of help them in some areas, that would be worth a try. We should try some of the ideas that some of the people have. I think that we have time on our side, that some areas are just naturally going to recover because the numbers of crabs is decreasing and the numbers of ground fish are so much lower that they are not going to have a detrimental effect, like they might have.”

Harris thinks that Zone 2 could also benefit from efforts to help the recruitment, like reseeding, and feels that there are enough areas where the numbers of existing urchins in Zone 2 could support either reseeding or recurrent enhancement efforts, as well as some level of continued fishing.

“I’m not sure what he’s basing that on,” Hunter said. “I don’t think he’s been in the water in Zone 1 for a while. He hasn’t had access to our survey data. If that’s his conclusion, that’s okay.” Then Hunter added, “You know, you probably could have an extremely limited fishery if you let 20 people go, or you only let them go for 10 or 20 days. But, how do you do that fairly? How do you do that safely? And, how do you keep it from becoming a gold rush — get all you can because it will be the last chance that we’ll ever have in the fishery. That’s what George (Lapointe) is struggling with.”

“We’re not running out of urchins!” Albion Goodwin, state representative from Pembroke, which is in urchin Zone 2 said. “There’s plenty of urchins out there. Just ask the urchin fishermen!” Goodwin disregards the research of the DMR scientists, like Hunter and Wahle. “What do we need scientists for to tell us about the fisheries?” Goodwin asked. “The fishermen can tell us about what’s happening in the fisheries. They’ve been doing it for 200 years. It all depends on who wants to fish.”

Steve Brown wants to fish. He’s a diver out of Jonesport. “Last year I would have said yes to a closure,” Brown said. “But this year I’ve seen a lot of urchins and I really did good this season. If the DMR was to shut it right off, boy, a lot of people would be in trouble in Washington County.” Brown has been leading the state’s divers for the last two years on the annual summer surveys conducted in Zone 2. Last year, Brown said that the state divers found more legal-sized urchins during the surveys in his zone then the previous year. “I know that there’s urchins in areas of Zone 2,” Brown said. “In Jonesport there were six trucks, every day, loading to the doors.” The DMR told divers like Brown that it was just a lot of effort in one area. But Brown said that he hadn’t seen the high concentrations of boats. It’s his feeling that the effort, at least in the Jonesport areas, was spread out.

Hindsight is 20/20

“The problem in the 80’s was how do we get rid of these damn things?” Harris said, regarding the proliferation of urchins that were wrecking havoc on the inshore vegetation up and down the coast. “For some reason, probably a decrease in ground-fish, the numbers of urchins started to increase and had a profound effect on the existence of kelp and other plants, to the point where huge areas of the bottom where turned into urchin barrens. After the urchins had been removed, the algae flourished, the red sort of crusty stuff, which is a perfect environment for baby mussels. With all the salmon pens and all of the aquaculture of mussels and everything, there has been a whole lot more mussel larvae in the water, than there used to be in the old days. And all of the new algae-rich habitat provided a perfect environment for baby mussels. In huge areas of the coast, the mussels proliferated and turned the bottom black. That provided a perfect feeding ground for the sea stars and the crabs and they’ve had a glorious time, particularly cancer borealis (Jonah crabs).

“Since there were already urchin fisheries on the Pacific West Coast, it was decided by the DMR that the thing to do would be to promote an urchin fishery in Maine for the Japanese market. Everything sort of fell into place around 1987 and it became a gold rush, sort of rape and pillage, strip the bottom and take everything, just bag it up and take it to the processing plants and let them get rid of what they didn’t want. Which meant that it would be dead before it could be thrown back.”

“We certainly participated in encouraging the start-up of the fishery,” Hunter said. “But, we didn’t have the authority to control it, or the knowledge or the will. We didn’t have the will to come forward and say that we needed controls. There were no controls for seven years, except that, starting in 1992, you had to buy a $89 license.”

“By 1990, I was already getting phone calls from fishermen in the Casco Bay region,” Harris said, “asking questions like, how fast do urchin’s grow and how fast will they come back?” The fishermen could see the potential problem, but the DMR had no regulations, no season. Finally a committee of processors, fishermen, and such, put together a set of tentative regulations and pushed a bill through the legislature.”

“For a long time we didn’t know who was running the fishery,” Hunter admits, “the Urchin Council or the DMR. We sort of

let the Urchin Council call the shots and it took a while before we realized that that’s not really co-management.”

“My view of the DMR is that it’s trying,” Harris said. “But, it’s also politically expedient in many cases to not try too hard, because they are so tied to the legislature for funding that it’s really very hard. I used to commiserate with Maggie Hunter’s predecessor. There were things that we agreed needed to be done, but if he had done them, he would have been assigned the job of checking lateens or something like that.”

Harris believes that the DMR should have been more proactive back in 1985, “But there was no incentive,” Harris said.

Hunter agrees that the DMR could have done some things better. “The last few years of the 90s, when we really should have been making some pretty heavy-handed cut-backs, we didn’t,” Hunter said. “We were using catch ‘per unit effort’ as an indicator of abundance, and that was a big mistake, I think. Because the numbers leveled off in 1998 and we thought, ‘Great, the fishery is stabilizing,’ but it really wasn’t. We saw this artificially inflated statistic because we were looking at only the most successful, hardest-working fishermen. I would say that that’s a mistake that the scientists made — relying too heavily on that indicator.”

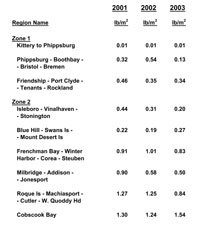

Biomass of sea urchins of all sizes at depths less than 50 ft., untransformed stratified averages in pounds of urchins per square meter.

Biomass of sea urchins of all sizes at depths less than 50 ft., untransformed stratified averages in pounds of urchins per square meter.

|

Solutions

While the DMR, in general, is pessimistic, many, including; Harris, Brown, Murray, Urchin Council Chairman William “Killer” Smith and urchin hatchery owner Bob Peacock, are optimistic that reduced pressure and new reseeding programs can turn the fishery around.

“I think that if we had hatcheries down the coast,” Brown said, “we could make a difference and the fishermen could be responsible for putting something back into the fishery.” Brown thinks that seeding way up high, away from most of the predators, way up into the kelp, would allow the urchins to grow very fast, “Especially if they’re up into the good feed,” Brown said. “Within a year, they’d be an inch. Two years, they’d be harvestable, I know they would be, and I think that that’s the way to go.”

But, many suggest that any reseeding efforts will fail, as did the reseeding projects attempted by the DMR, near Cape Elizabeth. “That was one attempt that may have failed,” Harris said, “It might also have failed because at that time it was in sync with the highest populations of Jonah crabs. That spot might not have been the spot that I would have picked, anyway.”

“In general, hatchery replenishment of wild fish stocks has not been successful in other fisheries, in other parts of the world,” Hunter said. Although, she does point out that there have been some exceptions. “In Japan, they have had some success in reseeding with dime-sized urchins.”

Bob Peacock is anxious to give it a try. His urchin hatchery, located in Lubec, is ready to produce 40 million urchins per year for reseeding in the Cobscook Bay or other areas. Peacock estimated that the reseeding of the bay would cost $200,000.

“To me, that was the first positive thing I’ve heard in a long time,” Murray said. “This gives the fishermen a chance to put something back. To me, it’s the hope of the industry.”

Harris admits that adding high concentrations of young urchins to areas of the Maine coast might be a little like playing God. But, he believes that the timing is right for reseeding efforts. According to Harris, the pendulum is about to swing back, the Jonahs are decreasing, the kelp is already growing back and the urchins will slowly increase because of the kelp. Re-seeding will only accelerate that process.

“The problem with reseeding is where do you put the urchins, and who owns them?” Hunter asked. “That’s where the scallop spat project has also gotten bottlenecked. Who has the right to fish those?”

Hunter favors a local management concept. “What we need to be able to do is access and manage more locally,” Hunter has been saying for several years. “More like clam management. For one thing, urchin fishermen move about a great deal within the fishery, and I don’t think that has been good. It doesn’t foster stewardship. It means that they have traveling and hotel expenses that they have to recover from the fishery, so it brings added pressure. A local management scheme would probably have people fishing locally and only during the months when their urchins where at the best quality. It would mean much shorter seasons.”

Hunter suggests that once that local infrastructure is in place, “You could try reseeding projects and possibly mandatory participation in reseeding.” The problem that Hunter foresees is trying to develop that infrastructure while the fishery is at 10 percent of it’s original size. “Until you have local control over an area, as you do with clam flats, these reseeding projects are going to favor private development. It’s easier for somebody to get an aquaculture lease and put their own urchin spat on their lease site. That’s the only way to insure ownership within the infrastructure we have now.”

Goodwin said that the situation won’t get critical for the fishermen until Lapointe issues his decision. “There’s no urgency right now,” Goodwin said. “The urgency will come long about September, if he puts the word out for the fishermen not to gear up. Then we’ll know that we’ve got a fight.”

“We have to have the fishermen up front,” Harris said, “directly participating. We need to rely on their wisdom, rather than the ‘Expert,’” Harris said. “This has to be a real collaboration with the pros that are out there making a living at it. Because they are really insightful and bright and observant naturalists, these fishermen. It’s stupid to think that someone who sits behind a desk, just because they have a degree and a lot of extra schooling, that they know more about what’s going on down on the bottom than the people who make their living there. It has to be a real collaboration, where you’re working together with the fishermen, and not telling them what they should be doing.”

Hunter hopes that the participation at the urchin summit will be high. “I’m not sure what to tell the guys from Zone 1,” Hunter confessed. “They may still be hoping for a season and are coming to the summit to try to convince George to create a short season. I think the summit will be the place for them to put their plan out there. But, I’d hate to get people’s hopes up. We’ve been sort of debating, here, how to handle that at the summit. We’re just not completely sure what to say.”

|

Problems from page 1 April 2004

Problems from page 1 April 2004