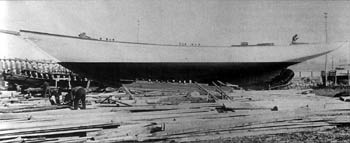

The James S. Steele at the Story shipyard in Essex Ma., end of 19th century. Considered the antithesis of the clipper schooner, the Tom McManus design reduced deadwood, added a deep rockered keel and overhanging ends. The result was a commercial hull that would come across the wind in seconds, faster than racing yachts and safer than clippers. Photo courtesy The Dana A. Story Collection, Essex Shipbuilding Museum, Essex, MA |

Stories of fishermen racing have been, for the most part, based on events of the late 1800s New England banks fishery. Fishing moved offshore to the banks, including the Grand Banks, in the 1830s. The longer trip meant longer-term preservation and the salt banker was the answer. Salt was brought out and the catch salted on board. Economic changes in the 1840s sent greater numbers of boats to the banks. When the country expanded west, the Erie Canal and railroads shipped goods, including salted, dried, pickled and smoked fish. Another change was the rapid switch from salt to ice for cargo preservation. A perishable cargo with a now-perishable preservative contributed to the demand for speed. That speed, however, was gained in boats unlike the deep, weatherly pinkies, long used in the Gulf of Maine. The boat of choice for the banks—narrow, shallow and burdensome—evolved from the sharpshooter. These clipper schooners were fast, but slow in tacking, leaving the shallow hulls open to being thrown on their beam ends. Also, to carry their large sail area, they had a long bowsprit, or “widow maker,” from where, on the icy winter banks, many a widow was made.

The measure of a captain returning from the banks was his willingness to put on a full press of sail for the race to market. Driving the boat, usually a two-masted schooner about 60 feet overall, was imperative, in all weather conditions. The run was usually from the Grand Banks or Georges Banks. The weather could be frustratingly calm, exhilarating or terrifyingly horrific.

James Connolly wrote stories of Gloucestermen in the early 1900’s. A mix of fact and fiction, one tale tells of a race between a Gloucester fishing schooner Captain Wesley Marrs on the Lucy Foster, and an English yachtsman on the Bounding Billow. They meet off Reykjavik, Iceland and agree to race to Gloucester. It opens with a poem:

‘Twas sou’ sou’ west

Then west sou’ west

From Rik-ie-vik to Gloucester;

‘Twas strainin’ sails

An buried rails

Aboard the Lucy Foster.

Her planks did creak

From post to peak

Her topm’sts bent like willows!

“I’ll bust her spars”

Says Wesley Marrs

“But I’ll beat the Bounding Billow.”

Connolly and others like Joe Garland, Rudyard Kipling and Wesley Pierce romanticized the captains and blamed the owners for the notoriously high losses of fishermen and boats in the quest for speed. Between 1860 and 1899, 600 schooners and 3,500 fishermen in the Grand Banks fleet were lost. Annually there were about 300 boats in the Grand Banks fleet in those years.

Most who stood to make a profit might be considered complicit. Owners, architects and builders focused on speed. Fishermen, dependent on their share of the gross profits, worshipped it. Adding to the difficult-to-handle boats, was the fact that crews were primarily fishermen and learned to sail fast out of necessity. They had not had the training a merchant sailor typically would have. They were also sailing with equipment that did not get the maintenance and upgrades that merchant ships often got.

As for the designers, ignorance may have been added to complicity. It was not until the McManuses of Boston began designing boats with deeper draft, more drag and reduced weight aloft, that casualities began to fall in the 1880s. The design changes the McManuses made became common on the banks. Tom McManus, like his father, the sailmaking patriarch John H., sailed aboard fishing schooners and knew first hand the realities. Since his teen years, Tom was concerned with the unseaworthy characteristics of the fishermen. He spent years trying to design the widow maker out of existence and finally did with his Indian Head schooner. Its bow was projected out to where the bowsprit would have been.

The safety qualities of fishing vessels was an issue well publicized. Captain J.W.Collins of the U.S. Fish Commission led the crusade for safety in the fleet. He criticized the shallow clippers for being unstable, unresponsive and uncontrollable in rough conditions. Using a pen name, he published his opinions drawing experts under their own pen names into the debate. Advocating for deep draft cutters, he convinced the U.S. Fish Commission to lead the battle. They invited competitive designs and sponsored the construction of a very different schooner, Grampus 1886, designed by Dennison Lawlor of Boston.

Meanwhile the McManuses had produced the John H. McManus (1885), which was the fastest and most able of her day, winning the first of the great fishermen’s races on May 1, 1886. These fishing boats were faster through stays than the racing yachts of the era. Tom’s brother Charley also developed a method of weaving sail canvas that retained equal amounts of stretch and shrinkage. This was a major advance in sail technology and marked the beginning of the McManuses’ work with Edward Burgess, designer of three consecutive America’s Cup winners of the era.

The America’s Cup race began in the 1851, when England was at commercial heights with the U.S., shipping enormous quantities of cotton from the south to its mills in England. A challenge was made by its former colony. The challenge was logically to be at sea.

The business interests in England were merchants and mill owners fattened by the cotton trade. The Americans were merchants with less experience in the yachting world. The New York merchants engaged a boat builder/designer and hired a pilot boat captain to sail the challenger. Pilot boats sailed out from ports to large vessels unfamiliar with the port they were to enter.

They raced to be the first to reach the inbound vessel and put a pilot aboard who could guide the ship in. These small-vessel skills made them likely candidates for captains in the challenge, which became the America’s Cup. America won, but the Civil War intervened and the next race was not until 1870. The English challengers with “professional” crews and gobs of money were not up to defeating the crews of American defenders, captained and crewed by fishermen and coaster men, many of whom were from Maine. The cup race was promoted and funded by a group, or syndicate, of New York merchants and businessmen. The reputation of Maine fishermen and coasters brought the syndicate to Maine to recruit crewmen.

Many crewmen were from Deer Isle and by 1895, the entire crew of the defender was from Deer Isle. The boats they crewed on were descendents of the banks schooners from Tom McManus’s drawing board. The Cup race, which the syndicate considered exciting, was one August afternoon, a few miles around a course, in one set of weather conditions. Pretty lightweight stuff for crewmen who had sailed three days in a January hurricane, aboard an ice encrusted schooner, taking green water over the rail, racing home from the Grand Banks with a hull full of cod.

|