|

Her father, who had regular health problems, occasionally waited on tables and later opened a barber shop. At twelve, Margaret also worked in the 5 & 10 cent store. In high school, she studied typing and shorthand with hopes of having skills to market. Organized and competitive, she joined the first Skowhegan High School girl’s basketball team as a freshmen, in 1912, and was the team’s captain when they won the state championship in her senior year. She maintained contact with much of the early network of friends and acquaintances she established in those years.

The First World War began in her last year of high school. News of the war and local fatalities were regularly in the news. After high school, Margaret did not have the money for the teacher’s college in Boston she had hoped to attend. Instead, she went to work for the local telephone company as an operator. It was there that she met Clyde Smith, in 1916. These two events, the war and meeting Clyde, affected both her decision to become a politician, and the kind of politician she later became.

Clyde Smith, a Skowhegan businessman, recently-divorced and twenty years her senior, struck up a relationship with Margaret. Of course, according to the social mores of 1916, establishing a “relationship” could be defined as a brief chat, a ride home from work in Clyde’s( then rare in Maine) automobile and maybe sitting on Chase’s front porch together. Smith was also a politician, an effective public speaker with a gregarious style, and an experienced Republican party officeholder. After trying a short stint as a school teacher, she decided it was not for her and returned to the telephone company. Two years later she had a job at the Skowhegan Independent-Reporter. She did about every job there, including business manager, in her eight years with the paper. The paper grew and Margaret was given credit for helping that to happen.

In the 1920’s, the American workplace was changing. Women had worked in factories since first being set up in the 1840’s, but there was a growing demand for clerical workers in the 20’s and women were taking these higher-paid positions. In the 1920’s, a variety of women’s clubs were established, some in response to what was seen as a new era of opportunity for women. Chase, long an organizer and active in group activities, was a member of various women’s groups, further developing her organizing and networking skills. The Business and Professional Women’s Clubs was a national organization established to promote self-help and women’s solidarity. Chase started one in Skowhegan. In 1923, as a committee chair, she represented the Maine delegation in Indiana at the national convention. As a candidate for the presidency of the state BPW, Margaret was considered politically neutral. Later in her career, she acknowledged the political education she got in the BPW. Among other things, she learned mediation, supervising, speaking, negotiation and leadership. She had awakened her own abilities.

Throughout the 1920’s, Clyde was on the fringes of what Chase was doing. Both were politically-active, and Chase was elected Maine State Republican Committee woman, in 1930. Clyde held other political offices in the 20’s before being elected to the Maine House, in the 1930’s.

Both were well-known, Chase as a highly-regarded woman and politician in her own right while Smith sought the governorship. Maine was virtually a one-party state at the time, but within it were the typical range of views. Clyde, a supporter of labor rights, was known by his party to have a “twinge of radicalism.” They married in May, 1930. Clyde and Margaret regularly campaigned together, and did so for the governorship, in 1936. But at the last minute, Clyde dropped out and ran for a house seat from the second district and won. With Margaret as one of two staff members, they left for Washington.

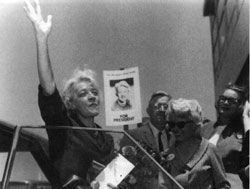

Presidential candidate Margaret Chase Smith arrives in San Francisco for the Republican National Convention, 12 July 1964. The first woman elected in her own right to the U.S.Senate and the first to be elected to both the House and the Senate, she ran for the republican presidential nomination, never for president. She came in 2nd after Barry Goldwater. Carrying here her trade mark roses, she was in office for 32 years. Photo courtesy Margaret Chase Smith Library. |

Clyde had a heart attack in 1938. Margaret ran the office, began travelling for him and doing speaking engagements. She was developing her own voice, supporting labor legislation, protection for women, and increased military preparedness.

Clyde ran again in 1938 and won. He planned to run again in 1940, but with his health condition critical, he urged Margaret to file papers for office in her name. Clyde died in Washington during the Maine convention. The day after the funeral, a special election was announced. Republican leaders, on Clyde’s request that his wife be considered for the office, acknowledged her candidacy. One candidate challenged Mrs. Smith, and there was a vote, which she won.

There is a precedent for widows finishing congressmen’s terms. At the state level, they can be appointed. U.S. Congressmen cannot be appointed, they have to be elected. The rumor persisted that Margaret Chase Smith was given her husband’s incomplete term and was characterized by opponents as getting a “free ride.” In reality, she not only had the experience, knowledge of her husband’s political business, and the necessary skills, she also won the election. She was probably better-qualified than her husband as a grassroots politician. Smith ran her campaigns on a budget considered tiny, even in the 1940’s. She relied on volunteers, and her funding remained this way until her last campaign, in 1972.

Getting elected to the House or Senate is only one part of the congressional equation. Having the skills to navigate and effectively function in the political maze of the congressional system is probably at least as important. Few who knew her would deny Margaret Chase Smith’s abilities in this area. Smith sought and got some of the most difficult to get and powerful committee assignments in congress, not the least of which was the Armed Services Committee. On these committees she took on tough and controversial issues.

To put this in perspective, the 1940’s were a time when Smith always arrived early for meetings, to avoid entering a room where the men would all stand, as was the custom, in recognition of a woman. She didn’t want to be recognized as a woman, with all the cultural baggage that went with it; rather, she wanted re-spect as a member of congress. She knew congressmen had said congress was no place for a woman.

In 1942, Smith was assigned to the House Committee on Naval Affairs. It was at this time that she met Bill Lewis, the most-influential person in her public life. Considered her biggest asset, he was Smith’s informal advisor and became official administrative assistant after her 1948 Senate seat win. Born in Oklahoma in 1912, with a law degree from the University of Oklahoma and an MBA from Harvard, he started out working as a prosecutor for the Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington, D.C. Lewis was working with the House Naval Affairs Committee in 1942, where he began an association with Smith.

Lewis’ expertise, legal education and encouragement soon became very important to Smith. His legal background gave Smith another perspective, but he was also an astute manager of Smith’s public image and a screen for what was thrown at her. For the rest of his life he would remain an assistant, advisor, confidant, friend and fellow traveler. During WWII, armed services work was the highest priority and Smith was a vital part of it. Her long-running support for military preparedness was in tune with the times and Maine’s depression-era shipbuilding capacity ready for congressional recognition. Military production and bases were brought home by Smith during and after the war. Always popular in Maine, it was the events which followed the war that brought her to national attention.

Russian aggression in Europe after the war, the 1949 Chinese revolution, from which another communist state emerged, and the communist North Korean invasion of South Korea all put communism in the news. The junior Republican senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, exploited the situation. In several speeches around the country he said, “I have in my hand a list of 205 Communist agents in the Truman administration.” He called it a “spy ring,” working and shaping policy in the State Department. He later changed it to 57 names, but many were basically Democratic party supporters.

McCarthy, by way of threats, falsehoods and personal attacks, had congress and the country on the run from a new Red Scare (the first was in the 1920’s). It so mimicked the Salem witch-hunt of 1691, where a minister offered up a list of names, that it, too, was called a “witch hunt.” People in government and business – Communist and unpatriotic alike – were considered the same. Being seen with a suspect person, or book, or heard making an unfavorable remark could end a person’s career.

Even the members of the U.S. Senate, “the most exclusive men’s club, among the most-educated and most-powerful men in the country,” were shaking in their boots. Afraid of confronting McCarthy’s falsehoods, the politicians instead gathered around lame legislation that looked anti-communist. While these blowhard ninnies cowered in the corner in fear of the bully McCarthy, on June 1, 1950, Margaret Chase Smith strode into the Senate, took the podium and declared that congress was no place for weenie boys.

Smith had prepared what she called a “Declaration of Conscience,” in response to the devastating effect that McCarthy’s duplicity and manipulation had on the nation. Addressing the general malaise in the country caused by “the confusion and the suspicions that are bred in the United States Senate,” Smith took them to task. In the approximately 1,800 word speech, she said the administration has “confused the American people by its daily contradictory grave warnings and optimistic assurances.” She also said that, “Those of us who shout the loudest about Americanism are all too frequently those who... ignore some of the basic principals of Americanism—

The right to criticize;

The right to hold unpopular beliefs;

The right to protest;

The right of independent thought.”

Only six other Republican senators publically concurred with the declaration.

Smith’s entire adult life was framed by war and politics. Her political life brought her closer to the realities of defense and waging war. Beginning with WWI in high school, to WWII, Korea and Vietnam, her committee work was divided between military committees and the social legislation of early days. Toward the end of her life, she was criticized for her military posture. She was a staunch “hawk,” during the time of unprecedented demonstrations against the Vietnam war. Her stance had been to “walk softly and carry a big stick.” Talking tough was the combat of the Cold War. Smith was not alone on the front-lines, but some of her verbal salvos were heard above those of others. |