Understanding Life Around

Eastern Maine Coastal Current Topic

of Machias Conference

by Sarah Craighead Dedmon

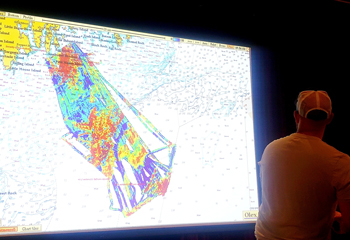

Steuben fisherman Mike Sargent spoke to the assembly showing them how he utilizes technology like this Olex mapping system to make more efficient use of his traps and time. “From the water temperatures to the current flow, it all has a story to tell if we know how to read it,” he said. Photo by Sarah Craighead Dedmon.

What do softshell clams, Washington County census data and sturgeon have in common?

On the surface, not much. But for participants in a new fisheries management initiative, each one plays a vital part in the story of life surrounding the Eastern Maine Coastal Current, a nutrient-rich current that descends out of Canada and runs the length of Downeast Maine.

The Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries (MCCF) is leading the Eastern Maine Coastal Current Collaborative, or EM3C for short, a partnership with the Maine Department of Marine Resources and NOAA Fisheries. Together with dozens of partners, the EM3C hopes to create science that will one day support Maine’s largest ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) effort yet.

Though conference attendees acknowledged Maine has been using elements of EBFM for years in various fisheries, this new initiative differs in its magnitude. EM3C’s study area stretches from the St. Croix River on the Canadian border, down to the Penobscot River, encompassing all aspects of life in and alongside the current.

“The ecological and

productivity potential

of the St. Croix River

is the highest on

the east coast.”

– Ed Bassett,

Passamaquoddy Tribe’s

Environmental Department

“We aren’t just focused on the salty pieces, we’re also thinking about how the rivers and lakes and streams are connecting to the coastal and offshore habitats,” said Dr. Heather Leslie, Director of the Darling Marine Center

Leslie gave the opening keynote address at the two-day State of the Science conference which drew more than 150 people to Machias June 17-18, where they heard from experts in diverse fields ranging from marine biology and oceanography to economic development and lobster fishing. “You can’t do ecosystem-based management without thinking about a place,” she said.

The conference schedule was divided to spend time on each of the current’s four major ecosystems: watersheds, intertidal, nearshore and offshore. In every segment, both human and ecological elements of the current’s ecosystem were addressed.

Ed Bassett spoke representing the Passamaquoddy Tribe’s Environmental Department, where his work makes him an expert on the St. Croix watershed. Bassett said the ecological and productivity potential of the St. Croix River is the highest on the east coast, yet its fishery went from “pristine abundance” in 1763 to total collapse in 1825—only 61 years.

“The fishery was so abundant, it ‘could never be destroyed,’ they said, and in 1825 it collapsed because of one dam,” said Bassett. Other threats, such as pollution, came in after the dam, extending the collapse.

“We’re still dealing with it,” said Bassett. Today the tribe insists on fishery co-management, he said, because others entrusted with that duty have not done well.

“Is there fertile ground for meaningful, inclusive co-management today? I think there is,” said Bassett. “It’s time to get the dust off the treaties, look at them and engage each other in this respectful cooperation.

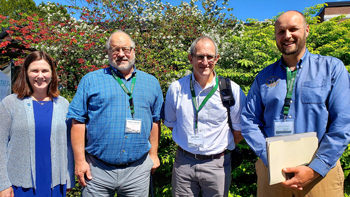

The Eastern Maine Coastal Current Collaborative is a partnership led by the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, together with the Maine DMR and NOAA Fisheries. Dr. Heather Leslie, left, opened with a keynote address sharing what her team learned about ecosystem-based fisheries management in their studies of the Baja California Sur region of Mexico, a fishing region with many similarities to Downeast Maine. From left to right: Dr. Heather Leslie, U Maine, Paul Anderson, Director Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, Jon Hare, Science and Research Director, NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center, and Carl Wilson, DMR Director, Bureau of Marine Science. Photo by Sarah Craighead Dedmon.

Sunrise County Economic Council Executive Director Charles Rudelitch spoke on the economic drivers along the coast of Hancock and Washington County, a region still primarily driven by a natural-resource based economy. Rudelitch said the total value of the region’s economy is roughly $3.5 billion, of which the lobster fishery contributes at least 10 percent.

“From an economic standpoint, we are essentially a one-trick pony,” said Rudelitch.

Speaker after speaker pointed to climate change as a factor the EM3C science must reckon with in order to be effective. In his presentation Tom Huntington of the U.S. Geological Survey said the waters in the Gulf of Maine are rising by 1.1 degrees fahrenheit per decade.

Filling data gaps

DMR Commissioner Patrick Keliher was called to Augusta for much of the meetings, but attended the final afternoon and delivered his closing remarks.

“What’s important about this group and the need for it to continue is that we can actually define it in a much clearer way,” said Keliher. “We need to simplify it, we need to decipher it, we need to kind of boil it down. That’s critical.”

“And it’s those data gaps. When Robin Alden came to see me two years ago now, to start talking about this whole concept, it spun into the management,” said Keliher, referring to former MCCF Director Alden, widely credited for kicking off the initiative. “And as we talked about it...we said, ‘We’ve got so many data gaps, how do we tie this all together?’”

University of Maine at Machias (UMM) Associate Professor Tora Johnson helped coordinate the event and was part of the follow-up conversations that happened the day after the conference. Johnson said the group determined some next steps which they believe will build on the momentum of the conference, including addressing those data gaps.

“Most of those are mapping data gaps, but it’s not just seafloor mapping” said Johnson, who runs UMM’s GIS Lab. “It’s mapping of lots of different things, including population structures of little-studied species.”

We’re learning more about alewives, we know a lot about lobster, and we know a lot about scallops, said Johnson, but there are other species we need to know more about, like rockweed.

“We need to understand what rockweed’s role is in the ecosystem, it’s not really fully known.”

“There are a lot of different questions that came up around aquaculture of all sorts, around seaweed aquaculture, salmon aquaculture, both land based and sea based,” said Johnson. “Also, what sociologically and economically it can mean. For instance, how many jobs can we have coming out of the different kinds of aquaculture? How much of that money would stay in the state, and what types of jobs would those be?”

“There’s a whole range of questions, and they’re not just biological, which is the entire point,” said Johnson.

“There are a lot of different questions that came up

around aquaculture.”

– University of Maine at

Machias, Associate Professor

Tora Johnson

During a presentation by Steuben fisherman Mike Sargent, attendees saw firsthand the incredibly detailed maps of the ocean floor Sargent and his father created using a tool called Olex. Many lamented the lack of similar maps in the Maine scientific community.

“We only have that in patches, and so we want to expand that,” said Johnson. “It’s not only that we’ll have all the depths in Machias Bay, it’s that we’ll have them and we’re going to gather them together and we will build tools for using the data in the most effective way.”

The group will also seek funding to build capacity, especially in the form of staff to assist with their goals. Already they’ve identified several ongoing projects about to start where valuable, EM3C-relevant information can be collected. “Some initial projects, places where that might be applied would be looking at some of the alewife efforts that are going to be coming down the pike, some of the coastal resilience work, and some of the salmon work,” said Johnson, adding that list is not comprehensive.

Lastly the group agreed to plan another conference, but schedule it at a more convenient time of year. Johnson noted that June is a tough time of year for harvesters and also for many scientists, who rely on good weather for field work.

In his closing remarks, Northeast Fisheries Science Center Director Jon Hare referred to the Passamaquoddy word for “ecosystem,” learning to pronounce it with the help of Ed Bassett.

“The translation is, ‘Our relative’s place,’” said Hare. “So if we think about this not as an ecosystem, but as our relative’s place, what do you want to pass on to your relatives seven generations from now?”

“This is a long run. It’s not a five-year project,” said Hare. “It’s a career-long project. This is a commitment, a long run to change how we think about managing in these systems.”