Maine’s Covered Bridges

by Tom Seymour

Robyville covered bridge in Corinth, Maine. Tom Seymour photo

Covered bridges are always sure to evoke nostalgia in visitors. These relics of days past represent a form of architecture that was at once pleasing to the eye and also extremely practical. But why cover bridges at all?

The answer to that question is so prosaic that many people fail to discern it. Many might say covered bridges were built so that travelers could find respite from rain and snow. Others might suggest that covered bridges were places where people could meet and talk, people who otherwise might have gone on their way with nothing but a nod to those traveling in the opposite direction. These things developed as a result of covered bridges but were not the real reason for building covered bridges in the first place.

The simple truth of the matter lies in what water does to wood. It rots it. For an example of how we still, today, take steps to protect wooden edifices and structures, consider how modern builders use pressure-treated lumber when constructing decks and balconies. Pressure-treated wood thwarts the ravages of standing water, at least for a far longer time than plain, untreated wood. Even after building with pressure-treated wood, most people take the extra preventative step by applying some kind of water-resistant sealant.

For another example, consider pilings used in construction of piers. A close look will reveal that each piling has a coat of fiberglass-treated cloth on top. In days past, sheet lead was used for this purpose. But no matter the method of covering, one thing was certain. That was that an unprotected piling would soak up rainwater, which would cause it to deteriorate in just a short time.

So considering the frugality practiced by our early New England ancestors, it only makes sense that they would build bridges that would stand up to rot, bridges that would last for years without much upkeep.

Bridge Amenities

Covered bridges served a number of purposes not related to crossing a river or staying dry during a thundershower. Covered bridges were the ideal vehicle for advertising. Businesses in nearby towns tacked their posters to the bridges, both inside and out. And while those posted on the outside of bridges lasted little longer than a season or two, those attached to the inside, out of the weather, lingered for decades.

During the age of patent medicines, posters and signs for all manner of fantastic cures made it to the side of Maine’s various covered bridges. These included not only nostrums meant to cure human ills, but also those designed for horses.

Traveling circuses, too, always had an advance person, armed with colorful posters, to go out and place their ads on and in covered bridges. Likewise fairs. County fairs, town fairs and every other kind of fair were advertised through posters tacked to covered bridges.

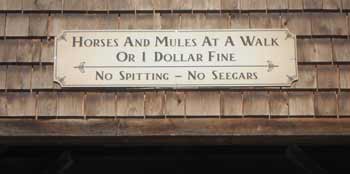

And always, placed over the front and back arch of each bridge, was a permanent wooden sign erected by the town. These usually indicated a fine for those traveling by horse or mule who drove their animals faster than a walk. The Robyville Bridge in Corinth had (and still does) signs at both entrances proclaiming, “Horses And Mules at a Walk or 1 Dollar Fine. No Spitting – no Seegars.”

But if any group in society benefitted from covered bridges it was children. Covered bridges held a certain charm for young people. The smell of pitch exuding from the wood on hot summer days, coupled with a sawdust scent mingled with horse manure was, if not entirely pleasant, at least distinctive. And once experienced it was never forgotten.

This can still be experienced at the covered bridge over Blackburn Stream at Leonard’s Mills in Bradley. Leonard’s Mills, a reconstructed 1790’s logging community, features Living History Days each spring and fall. These events include rides in a horse-drawn wagon and the route takes visitors over the reconstructed covered bridge there.

Back to children and covered bridges, most bridges spanned good-sized pools and here, children would while away summer afternoons with a cane pole in hand, angling for whatever kind of fish lived in the stream or river.

Once they became of age to go on dates, young people of yesteryear found covered bridges an ideal place for spooning. Many a young lad and lassie got their first kiss and hug under the protecting roof of a covered bridge.

Architectural Styles

Interior of the Robyville bridge with timber trusses sheathed on the exterior with vertical boards. Tom Seymour photo

Trusses, the heavy, lattice-shaped planks that made the side skeletons of covered bridges, differed from one another according to the style of the architect whose plans bridge builders followed. Unfortunately, few, if any, records exist of the names or anything else about the men who did the actual work. But the names of those who designed the various types of covered bridges are well known.

Prominent among these were Timothy Palmer 1751-1821, whose bridges were of the earliest variety. Palmer, a millwright and self taught carpenter and architect, used an arch in his construction, which meant that the bridge, depending upon its length, had one or several humps in the roadbed.

After Palmer, Theodore Burr used so-called “Palladian arches,” the same as Palmer, but Burr adapted his arches in a level manner, meaning that bridges built according to his plans had flat roadbeds.

But Palmer-style bridges incorporated massive timbers and these required considerable muscle to put together. The need for a covered bridge design that any small-town carpenters or mechanics could easily implement was clear. And so Ithiel Town came upon the scene, bent upon inventing a bridge design that any competent builders could construct. This style was called, “Town’s Lattice Mode,” and it incorporated any number of crisscrossed diagonals. In practice, these were overlapping triangles. As such, pressure on one triangle was spread throughout the bridge to all the triangles.

Town used wooden pins at every lattice intersection. The builders bored holes in the planks, reminiscent of post-and-beam houses and barns so common in the northeast. Town, like the others, profited by extracting $1 per foot royalties from the various towns that were about to build a new covered bridge.

Then sometime after 1840, all other forms of bridge design were eschewed in favor of the Howe truss, invented by William Howe. Howe replaced the upright posts used in bridge construction with iron rods. These had turnbuckles, which could be adjusted, loosened or tightened accordingly. Mostly they were probably tightened, though.

Existing Bridges

A good number of covered bridges remain in Maine, now mostly items of not only practical use but also historic significance. These are:

Lowes covered bridge in Sangerville, Maine was rebuilt in 2007 after being damaged by ice flows. Tom Seymour photo

• Babb’s Bridge, Windham/Gorham

• Bennett Bridge, Lincoln Plantation

• Hemlock Bridge, Fryeburg

• Lovejoy Bridge, Andover

• Lowes Bridge, Guilford-Sangerville

• Porter-Parsonfield, Porter

• Robyville Bridge, Corinth

• Sunday River Bridge, Newry

• Watson’s Settlement Bridge, Littleton

Bridge Miscellanea

Speed limit sign over the entrance to the Robyville covered bridge in Corinth, Maine. Tom Seymour photo

While the Maine Department of Transportation provided the official list of historic bridges shown above, a number of smaller, sometimes private, covered bridges dot the state. The covered bridge at Leonard’s Mills, although an authentic reproduction, is certainly a historical bridge. Many smaller bridges, built by private groups and individuals, lie scattered around Maine. Campgrounds, even golf courses, employ replica covered bridges as an added attraction.

Our Maine covered bridges are relics from our past and as such, are not only lovingly maintained (sometimes floods, even vandals, damage the old bridges) but stand as destination points for those wanting to feel and partake of a most interesting and useful bit of Americana. Artists as well as sightseers flock to these bridges. They are enduring symbols of Yankee ingenuity and will remain so for many generations hence.