When the Arnold Expedition Passed Through Skowhegan

by Tom Seymour

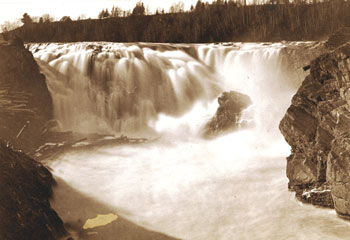

Perhaps the earliest known photo of Skowhegan Falls before the Weston Dam was built. Likely shot in the high waters of spring as evidenced by log drive remnants in water, left center, and on shore beyond. Arnold’s Expedition would have encountered lower water levels when it hauled their wooden boats, bateaux, over the ragged rock wall of the falls in October 1775 on their way to Quebec City. Photo collection Skowhegan History House. Courtesy Vintage Maine Images.

One day after the Battle of Bunker Hill (the battle actually took place on nearby Breed’s Hill but nonetheless became known as the Battle of Bunker Hill), the Continental Congress bestowed upon George Washington, of Virginia, command of the Continental Army then at Philadelphia.

It was Massachusetts militiamen who repelled two British assaults on Breed’s Hill. The third British assault was successful only because the Americans had run out of gunpowder.

Now, in July of 1775, with 16,000 mostly untrained soldiers (Congress soon after added another 3,000), General Washington, newly arrived in Cambridge Massachusetts, decided to take the battle to the enemy and in so doing, bring a swift and decisive end to the war.

The hastily-built white pine bateaux were leaky, heavy, essential and carrying them a part of what made the completion of the journey a near miracle.

Back in May, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold had captured Fort Ticonderoga from the British and in doing so, gave colonial troops control of a northerly route into America by the British in Canada. Now, in July, it seemed like a natural continuation of the course of events thus far to continue in a similar vein. To that end, Washington decided to send two armies through the howling wilderness of Maine and on to Quebec, to capture that British stronghold.

The two armies were led by Colonel Benedict Arnold, who was to travel through Maine in order to reach Quebec, and General Schuyler, and after Schuyler, General Richard Montgomery, who was to travel by way of Lake Champlain and on to Montreal and after taking that city proceed to Quebec to join with Arnold’s army. The two armies were to coordinate their attacks upon Quebec City and by storming the place at the same time, achieve a quick victory.

Washington felt that once under American control, the inhabitants would welcome American influence and even agree to become the “14th” colony, thus depriving Britain of a northerly route to America. The plan was sound, except for one thing. One of Washington’s armies, under command of Colonel Benedict Arnold, was to follow maps composed by British Chief Engineer John Montressor during a 1761 scouting expedition with Lord Percy to afford relief to British survivors of the Battle of Lexington.

Poling boats up shallow rivers, carrying boats overland to the next waterway, then over mountains with little or no food, dry, warm clothes and, for some without shoes, through uncharted wilderness for three months today seems impossible.

As he went, Montressor mapped the territory through which he marched, specifically the Lake Megantic-Dead River region. However, Montressor failed to include on his map Rush Lake and Spider Lake. He also omitted the various false mouths of 7-Mile Stream. And this was the map that Washington and Arnold used to plan the march to Quebec.

Montressor’s faulty and incomplete map made the journey look not only practicable, but easy. And so Arnold and his 1,100 men left Cambridge first by land and then by water to Gardinerston, which later was named Pittston. There, they took possession of 200 bateaux that were hastily constructed for their use. However, these bateaux were shoddily formed of green pine and proved a vexing problem for the length of the journey.

After this, the army stopped at Fort Western, which is now modern-day Augusta. There they tarried for several days, part of the army leaving Fort Western on September 25 and the rest leaving on September 29. From thence it was on to Skowhegan.

In Skowhegan

Following the Kennebec River up through Skowhegan, or “Sou Heagen,” as Colonel Arnold phrased it, was a lengthy process. Portions of the army, being spread out down river, variously camped in the river town of Canaan before making the next step in their upstream passage. Between Canaan and Skowhegan Falls, was a treacherous stretch of river called the Great Eddy. The Great Eddy is visible from Route 2 today and drivers familiar with the region’s history can reflect upon the difficulties Arnold’s men endured while battling their way up through whirlpools, whitewater and submerged ledges and rocks.

The ledges that presented such a terrible problem for men paddling and poling bateaux in October of 1775 have since been removed by blasting. But when Arnold’s men passed, the ledges at the beginning of the gorge formed what lumbermen would later term, “The Barn Door.”

In his 1761 journal, Colonel Montressor described the approach to the falls of Skowhegan this way: “It now makes a noble appearance, very broad and deeper than any we have yet met with. Its current is very gentle to the Nine Mile Falls; here it precipitates itself with great fury over high rocks, and being confined by high rocky banks, runs a quarter of a mile with vast rapidity, below which it forms a large basin, and then directs its course to the south.” The “basin” was the Barn Door and Nine Mile Falls later became Skowhegan Falls.

By now, the leaky bateaux were becoming a definite nuisance. Some supplies were already damaged, despite the fact that the army was not yet in the unspoiled wilderness that would mark the rest of their journey.

Motorists today driving to Skowhegan from the east on Route 2 drive parallel to the river at the same place where the Arnold Expedition passed in 1775. The oak trees along present-day Kennebec Banks have long been taken for their timber, but other oaks have sprung up in their place. And today, as it was back then, the countryside presented a stately scene. Arnold’s men remarked on the beauty of the trees lining the river. So except for being on a modern highway in a motor car, the view to the river is pretty much the same now as what Arnold’s men saw.

In speaking with a local, one of Arnold’s soldiers was told that the forest here, which in the past had been home to a healthy population of whitetailed deer, now held only few, if any, deer. The deer, according to the resident, were largely displaced by moose. Also, black bear were numerous and often visited riverside habitations. Atlantic salmon were present in the river at that time and could be seen ascending the rapids and falls.

Today, both deer and moose inhabit the forest around Skowhegan, but the Atlantic salmon are long gone.

The “Rips” below Skowhegan Falls drop 28 feet in a quarter mile. Shallow water in the fall barely covers the rough rock bottom visible along shore at right. Tom Seymour photo

The Falls

A group of Arnold’s men learned from their guide, Nehemiah Getchel, that a huge flint rock at the base of the falls was the vehicle that the Indians used to fashion flint tools and weapons.

Just downstream from the falls was a landing place that the Indians used when ascending this section of river in birchbark canoes. It was a small beach made up entirely of small stones. Here, Arnold’s men were obliged to haul their bateaux the approximately 30 feet up to the top.

Having gotten their bateaux up by sheer exertion and youthful manpower, the men were on the island and there, many of them camped. While buildings now dot the island, there were no structures there in 1775 save for a partly completed mill. However, the Indians had cleared some ground on some high ground and this was where Arnold’s men took respite from their labors.

Before even reaching present-day Skowhegan Arnold sent a scouting party under Lieutenant Steele to probe for the best course to reach Lake Megantic. While passing through Skowhegan, the men exchanged a quantity of pork for two fresh beaver tails. Beaver tail was considered a gourmet food item at that time.

Back in Skowhegan with the balance of the army, the weather turned cold. Captain Thayer wrote in his journal: “Last night our clothes being wet were frozen a pane of glass thick, which proved very disagreeable, being obliged to lie in them.”

Thayer went on to say: “The land is good, the timber large and of various kinds, such as pine, oak, hemlock and rock maple. The people are courteous, and breathe liberty. Their produce, (they sell at an exorbitant price) consists of salted moose and deer, dried up like fish. They have salmon in abundance.”

Captain Dearborn wrote of his group’s progress to Skowhegan Falls: “Proceeded up the river over very bad falls and shoals such as seemed almost impossible to cross, but after much fatigue and abundance of difficulty we arrived at Schouhegan Falls, where there is a carrying-place of sixty rods. Here we hauled up our bateaux and caulked them as well as we could, they being very leaky by being knocked about among the rocks, and not being well built at first. We carried across and loaded our bateaux and put across the river and encamped.”

Singular Incidents

Besides the soldiers, several volunteer officers accompanied the expedition, among whom was Aaron Burr. Additionally, two Penobscot Indians accompanied the expedition at least part way and other Indians helped in various ways, one of which included serving as messengers.

Local folklore maintains that Jacataqua, an Indian “huntress” was out with her dog when she met Aaron Burr and the two kindled a short-lived romance.

Another bit of Skowhegan tradition regarding the passage of the expedition says that while at camp, the men and their officers passed time in wrestling. One of the officers had a black servant and that servant was able to throw down each and every challenger. But then Captain Dearborn came to grips and landed the champion on his back.

Yet another local tradition holds that Arnold’s men raised a flagstaff and flag on the island. Locals Isaac Smith and Eli Weston helped in erecting the staff. It remains uncertain which flag the expedition carried, but whatever it was it was an American flag, the first one to be flown in Skowhegan.

The Arnold expedition finally made its way over the falls at Skowhegan and continued on to Quebec, where General Montgomery was killed at the outset of the attack and Colonel Arnold was wounded in the leg. These events resulted in the Americans losing their element of surprise and the attack failed.

But though it failed, it bought precious time for the rest of Washington’s army. Additional British troops, which were first destined to contend with the main army, were diverted to Quebec. It was a costly program, both in lives lost and fortune spent. And now it remains as a memory. But in Skowhegan, Maine, descendents of the settlers who met and aided Arnold’s men still speak of the trials and tribulations of that eventful time back in October, 1775.