Hunting Seasons

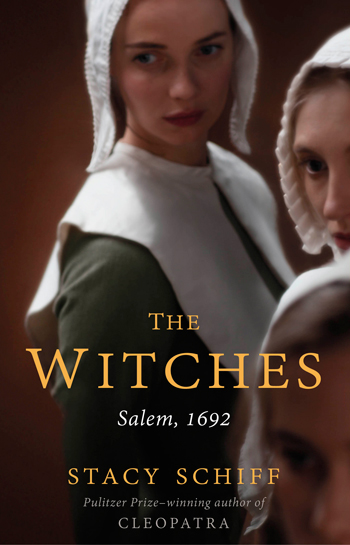

The Witches, Salem, 1692

Stacy Schiff

Little Brown Company

New York, NY 10104

498 pages; $32.00

It was this time of year in New England when one of the more bizarre periods of American history was unfolding. Not a uniquely disoriented period, but more patently bizarre. It was late spring when the first rumblings of terror would be unleashed over five months in and around Salem, Mass., in 1692.

Seemingly out of nowhere came accusations that would leave 185 area residents accused and 21 hanged by the end of September. In large part the accusers and the victims were women. Of the 185 accused, 14 women, 5 men and 2 dogs would be hanged by the neck until dead for practicing witchcraft. The carefully kept records of the Massachusetts court were not gender specific regarding canine offenders.

That this particular witch hunt involved accusations made by young women and involved coveted wealth and the vulnerability of class status, is among the well-known facts of the Salem witch trials. Making witches a tourist attraction in Salem 300 years later could be seen as further evidence of the self-induced amnesia that immediately followed the trials. Causes for the mass hysteria in Salem have been sought in period speculations. In the 1960s a theory was floated that grain stores had developed a mold that contained LSD, making the accusers and magistrates victims themselves. Some of the accusers had come to Salem from Maine where it was said the war with Native Americans had traumatized and made them vulnerable.

Salem had had earlier witch trials and hangings in the 1650s. Less well known on this side of the Atlantic are the 1675 witch hunts in Sweden, where 300 victims were beheaded and their bodies burned. Scotland at that time had its own witch hunts and hangings that also out numbered the Salem statistics—larger body counts without the LSD and PTSD.

Pulitzer Prize winner Stacy Schiff has published a well-researched and well-written history of the Salem witch trials. Schiff’s storytelling ability draws the reader through a fact-based, comprehensive, complex and unapologetic description of what went on in Salem in the summer of 1692. The book’s material is drawn from detailed records of the church and court system in Massachusetts and what seems like everything ever written about these trials and the participants. The source material is listed in 57 pages of reference notes and a 16-page bibliography at the back of The Witches, Salem, 1692. The picture that emerges is not the one to be found in most of what has been presented to date. Arthur Miller’s often-cited Salem witch trials play, The Crucible, addresses the human capacity for delusional assaults on the “other.” His play was motivated by the post World War II 1950s-era Congressional “witch hunts” for communist sympathizers. The 1996 film based on his play goes Hollywood at the end, centering the burden on a woman’s plotting over another’s husband.

Schiff looks at the victimization of “the female,” in this case, other witch hunts and contemporary society. The major players on the state and church side of the trials is a who’s who of early Massachusetts clergymen, politicians and merchants. Church and state were aligned in the British model of the day. Mather, Stoughton, Cheever, Parris, Hutchinson, and Walcott are a few of the names associated with these trials. They are also names that appear on many public buildings, monuments, street signs and in the histories of eastern Massachusetts. Many of the clergymen involved in the trials were Harvard College graduates. These were the same prominent men whose recorded statements would find elderly women guilty of making the 10-mile round-trip flight from Andover to Salem on a broomstick.

Some of these same men, born of financial, educational, social security and privilege, feared expressing their concerns, if not doubts, about the credibility of the accusations of witchcraft and the efficacy of the inevitable death sentences. So they didn’t. The frenzied accusations continued with pregnant women, the elderly and children chained in dank dungeons for months awaiting trial. It was one of their own, Thomas Brattle, a wealthy merchant who went to the leaders of the campaign to snuff out the witches they saw behind every bush, and asked them what the hell did they think they were doing. How could they be sentencing people to death for flying on broomsticks and turning dogs into witches?

Almost immediately, as though the courts had been awakened from a bad dream, the trials ended. Almost immediately, the cleansing effects of programmed amnesia set in to secure magisterial atonement.

Today, Salem’s tourism department characterizes the witch city’s past with cut-outs of black-clad women on broom sticks and inverted, pointy-hat slushy cones. The Salem witch hunt ended, but political use of the hunt of “the other” is sadly alive and well in the tool boxes of the world’s tyrants. The Witches, Salem, 1692 offers all you’ll ever need to know about the Salem witch trials and food for thought about the witch hunts—which, it seems, humans allow to pop anywhere.