Urchin Biomass Decline Has Slowed

by Laurie Schreiber

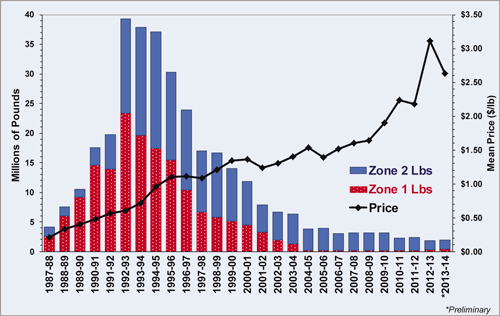

Maine sea urchin landings (millions of pounds, 1 million = 454 mt) by fishing season and zone,

and mean price ($ US) per pound, from dealer reports. Zone landings before 1994 are estimated

from county landings from NMFS port agent reports.

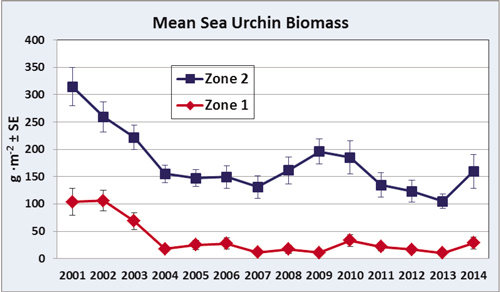

HALLOWELL—The rate of decline in the state’s sea urchin biomass slowed or stabilized after the fishing seasons were drastically shortened in 2004, according to “Monitoring Maine’s Sea Urchin Resource,” a new report by Department of Marine Resources marine resources scientist Margaret Hunter, published Aug. 1.

Biomass in all regions has declined since the survey began in 2001. The rate of decline was greatest between 2001 and 2004. Biomass is consistently lower in Zone 1, the western half of state waters, than Zone 2, according to the report.

“Declines between 2001 and 2014 seem to have occurred for all sizes of urchins, with no obvious long-term changes in size distribution for either zone,” the report says.

In 2014, the Cobscook Bay area had both the highest mean abundance for all sizes and the highest abundance of undersized, sub-legal urchins, at all depths. The Roque Island–Machiasport–Cutler–West Quoddy Head region had the highest density of legal-sized urchins. The Milbridge–Addison–Jonesport region had the highest density of oversized urchins.

“Although it is possible to estimate total and fishable (legal-sized) urchin biomass for each region and depth stratum by expanding the density estimates by the areas of likely urchin habitat, defining ‘exploitable’ biomass is not straightforward,” the report says. There are several factors that complicate that definition:

• Not all legal-sized urchins counted during a spring survey will have marketable roe the following winter. No attempt is made during this survey to evaluate roe content or quality. Harvesters simply inform the DMR about what they know of areas with “junk” urchins that they try to avoid.

• The selectivity of the survey divers is probably higher than that of a commercial diver. That is, they will count an urchin that an industry diver might not see or bother with.

• Many of the surveyed urchins are at low density—too low to support the efforts of a diver or dragger.

• There’s also no rigorous estimate of the threshold density of urchins required for harvest.

“Despite these problems, total and fishable biomass estimates could still be useful as long as they were clearly defined and used as indices,” the report says.

The report finds a decline in harvester licenses and landings that corresponded with the decline in biomass.

Mean sea urchin biomass (grams per square meter) from the spring dive survey

by zone and year with standard errors.

State licenses specific to sea urchin diving and dragging were introduced in 1992. Two years later, the number of licenses peaked at 2,725. Twenty years later, that figure is down to 317—156 divers, 139 draggers, 10 rakers, and 12 tribal (mostly draggers). Forty-seven divers, fourteen draggers, and one raker were licensed for Zone 1; the rest were Zone 2.

Landings grew steadily from 1987 to a high of 17,821 metric tons (39 million pounds) valued at $23.5 million during the 1992–93 season, then declined due to stock declines, management actions (including shorter seasons), and harvester attrition. Preliminary data put landings for the 2013–14 season at 872.6 mt (1.92 million pounds) valued at $5.1 million.

But the average price per pound has climbed steadily from 1987 to 2014, reaching a high of $3.11 per pound during 2012–13.

The three towns that had the highest urchin landings during 2013–14 were Lubec, Jonesport, and Tenants Harbor. In 2014, the Maine urchin fishery was the eighth highest in both weight landed and ex-vessel value.

According to the report, the price of urchins depends on many factors, including quality, worldwide supply and demand, which is impacted by seasonal holiday markets, and the Japanese yen–US dollar exchange rate.

“One measure of ‘quality’ is the roe index — the percent of body weight of the useable roe, which determines yield,” the report says. “Useable roe depends on roe color, texture, form, and taste, and the nature of the buyer’s market.”

Mean roe indices usually peak in February as the urchins approach the late winter spawning season. “In the 2013–14 season, an 8% urchin — considered poor quality but acceptable when demand is high or the buyer wishes to keep a loyal harvester — generally earned $1.35 to $2 per pound for the harvesters, while a 12% urchin earned about $2.30 to $2.80 per pound,” the report says. “Above about 16%, the relationship is less predictable, perhaps because some of the higher roe indices occur after December, when worldwide demand (and prices) often drop. Also, buyers sometimes place a cap on the maximum amount they can pay, regardless of quality.”

The number of active Zone 1 harvesters increased by 19% between 2011–12 and 2013–14, concurrent with a lengthening of the season from 10 days to 15 days in 2012–13. The number of Zone 2 harvesters declined about 21%.

There is reason to expect that Maine sea urchin harvesters, particularly divers, “will soon ‘age out’ of the fishery, since the mean age of Zone 1 divers was 50 and the mean age of Zone 2 divers was 46,” the report says.

According to the report, most Zone 1 fishing trips in 2013–14 were in the Tenants Harbor area near the eastern boundary of Zone 1. More than 90% of Zone 1 landings were caught east of Pemaquid Point. In Zone 2, about 86% of dragger landings and 38% of diver landings were caught east of Roque Island, off Jonesport, in Washington County; the rest were distributed fairly evenly across the rest of the zone.

Higher catch per unit of effort rates in Zone 1 during 2009–13 have been accompanied by a decline in roe content.

“Although changes in roe content could be attributed to climate change, a series of bad weather years, or other environmental factors, Zone 2 roe did not exhibit as steep a decline during the same time periods, suggesting that Zone 1 harvesters may have changed their fishing strategy, from targeting high quality urchins to targeting higher volume, poorer quality urchins,” the report says.

There may be minimum and maximum size limit compliance problems in the fishery, the report says. And the extent of discarding is not well documented, the report says.

“It has varied tremendously, even between divers on the same boat, from less than one bucketful per day for one diver to over half the catch of another diver,” The report says. “Dragger discard rates vary greatly depending on the underlying size structure of the population being fished.”

The report continues, “The fate of the (mostly small) urchins that are culled from catches is not known. There is evidence that green sea urchins exposed to extremes of air temperature or rough handling may not survive, depending on the length of exposure. Temperature extremes are common during this fishery’s season. Even if they survive exposure and handling, urchins that are culled from a dive vessel anchored in deeper water away from the urchin beds, where the bottom generally lacks feed, may be lost from the system. There is also evidence that dragged urchins can be mortally damaged (punctured, crushed, or de-spined) in the drag, especially in scallop drags, which are heavier than most urchin drags.

For the full report, visit maine.gov/dmr/rm/seaurchin/datareport2015.pdf.

Urchin harvest video at http://www.cnn.com/2015/01/21/living/maine-sea-urchin-diving-feat