B A C K T H E N

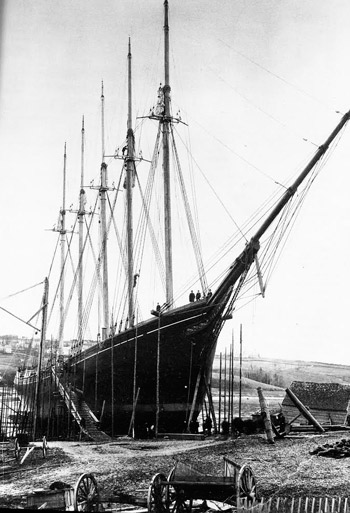

A Highly Steeved Lance

Waldoboro, November 1888. The five-masted schooner Gov. Ames, 1,778 tons, a centerboarder, and very heavily built, awaits her launching from Leavitt Storer’s shipyard. Note the great highly steeved lance of a jibboom. Note also the rigger at the mainmast head bending the main topsail—the topmast is 56 feet long, its truck 156 feet above the waterline. The Oregon pine foretopmast is 22 inches in diameter.

The Ames, built for the coastal coal trade, was initially intended by her Massachusetts owners to be a four-master, but it was realized in time that her sails would have been much too large.

As the first East Coast five-master, the Ames’s construction created a sensation. Pride goeth before falls, however. Caught on her maiden voyage by a “young hurricane” fifty miles southeast of Cape Cod, splices in the rigging pulled out, leading to the collapse of all five masts. Although two masts were salvaged and the rig cut down three feet so that the rigging could be reused with longer splices, the repair bill at Boston amounted to nearly one-third of her $90,000 cost.

The Ames’s near loss occurred soon after the loss by dismasting of the two-year-old Bath-built schooner T. A. Lambert, the first four-master to be lost. However, news that the two-year-old Camden-built four-master Pocahontas had netted her owners 42 percent of her cost in one year—this at a time when square-riggers were being sold wholesale to foreign flags or to be cut down for coal barges—confirmed the conviction that only big schooners could ensure the future of wood and sail, provided that their masts could be kept in them.

In the ensuing debate concerning sparring, one suggestion regarding the Ames, rumored to have been endorsed by the great Boston designer Edward Burgess, entailed lowering both the foremast and the spanker mast—the aftermost mast—by ten feet, so as to improve the staying angle of the shrouds at the hull’s narrower ends. (The Ames’s foremast was stepped ahead of the anchor windlass.) Another idea was to move the foremast aft, thus improving the shroud angle, reducing the effect of pitching on the topmast, and permitting the shortening of the seventy-six-foot-long spanker boom. Pilot Murdock of Bath proposed countersinking an iron band into each mast halfway to the top, with eyebolts for shrouds. Sails would run on a stout iron rod from cross trees to the deck.

A retired Ellsworth captain sagely observed: “There has been no successful invention or contrivance produced to make the heavy sails of the schooner any smaller or more easily managed. Whims and ways have been tried but always at the expense of the full propelling power of the canvas used .... Such sails [as a 1,150-pound spanker] are stiff in their disposition and it would be well to reef them snugly before the blizzard sets down on the wish.” The loss a year later of the splendid new four-master Millie G. Bowne by dismasting on her maiden voyage began the chorus anew.

The Gov. Ames, meanwhile, was putting her oceangoing capabilities to the test. First, she joined the great fleet taking lumber to the booming Argentine, loading 1,896,000 feet of spruce. Then, after a year in the coastal coal trade, falling rates sent her boldly off for San Francisco. She made a creditable passage of 141 days from Cape Henry to San Francisco, despite predictable difficulties off the Horn. Captain Davis wrote in the abstract log,

“This is hard usage for a coal-laden schooner of the Gov. Ames’s build, with long masts and heavy topmasts.” After a stint carrying coal from the Northwest to San Francisco, she took lumber to Australia, returning with coal from New South Wales to Honolulu. After two more voyages in the coal trade to San Francisco she returned to the Atlantic with lumber for Liverpool, and then rejoined the Atlantic and Gulf coasting business.

Her master for her final eight years was Captain Albert M. King, a genial Nova Scotian. William Gill, who signed on as mate for a trip carrying coal from Newport News to Bangor, suffered severe rope burns to his palms due to a sailor’s incompetence handling a halyard on a winch. He recalled: “Captain King took charge. This normally quiet, peaceful man turned into a hellion. He did not give those Portuguese a chance. He was right after them. I went down to the cabin, and Mrs. King poured some Friar’s Balsam over the palm of my hand. That made me jump. The cure was worse than the disease. She tied them up with gauze, but they were very painful.

I went back on deck. I couldn’t do much, but those Portuguese sailors stepped around as they never had before.”

In December 1909 the Ames went aground in a gale on Wimble Shoal, twenty-five miles north of Cape Hatteras. Mrs. King, wrapped in blankets and lashed in the rigging, was crushed by the falling mainmast when the hull broke in two. All hands but one, including Captain King, were lost.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Days Work, Part 1, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860–1920, Part II. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, 12 Starr St., Thomaston, Maine. 800-582-1899.