Maine in the Civil War

by Tom Seymour

Blaikie Hines, a civil war re-enactor. The Black Hat Brigade, which many Maine men were in, wore black hats and black uniforms. The rifle is an original Sharps carbine meant for cavalry use. Belfast Historical Society Photo

Maine and Mainers played a prominent role in the American Civil War. From the war’s inception in 1861 to its end in 1865, Maine soldiers and sailors answered the call to duty, with 73,000 Mainers serving in the army and navy. This was the highest number of people serving in the war in proportion to population, of any state in the union.

But this degree of pride and patriotism took its toll on the home front. Prices of durable goods soared, as did unemployment. Ship building, a major industry for coastal Maine towns plummeted, never to return to pre-war levels of productivity. And, of course, Maine suffered a great loss of life among her men who went to war.

Beginning this year, 2013, Maine libraries, historical societies, museums, regimental societies and other non-profit entities are participating in The Maine Civil War Trail, a statewide program designed to teach, enlighten and bring history alive. Each participating site will feature relics, artifacts and interpretive programs describing how the war touched upon that particular location. This is part of a four-year, sesquicentennial observance of the Civil War, which began in 2011 and will run through 2015. Also note that 2013 is the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, where Mainers played such a prominent role.

Two Towns

While locations up and down the coast of Maine offer presentations and programs, this article will describe the effects of war on two coastal towns, Belfast and Thomaston.

The Belfast Historical Society & Museum’s contribution to the Maine Civil War Trail is their exhibit, The Homefront in Belfast. In addition to displaying a Civil War flag quilt made by the ladies of Belfast in 1864, the exhibit will feature guest speakers, as well as a number of artifacts and displays featuring original letters, documents and newspaper clippings describing local opinion regarding the war.

The pistol, an 1860 .36-caliber Colt Army revolver, appears to be a replica rather than an original. A bayonet lies behind the belt, the copper container is a gun powder container for muzzle loaders and a leather pouch with US emblem. Belfast Historical Society Photo

Belfast

Belfast, like other towns, suffered its share of losses. Out of the 858 Belfast men who went to war, 100 died as a result. This, from a town with a population of 5,065. These were by-and-large, young men. Many of them, anxious to enlist, lied about their age. The youngest of these who paid the ultimate price was Michael Rariden, an Irish boy of 15.

While the overall majority of those who served in the war were single, one-fourth of those who died from Belfast were married and most of these had at least one child.

Belfast men fought in many of the war’s major battles, fighting and often dying, in places like Gettysburg, Bull Run, The Wilderness, Fredericksburg, Irish Bend, Port Hudson and Petersburg. Also, many Belfast men served in the navy. One out of 11 Belfast men who died served in the navy.

Nor did men from Belfast escape the horrors of being captured by the enemy and sent to prison. In fact, six Belfast men died while being held in the infamous confederate military prison at Andersonville, Georgia.

The Homefront

Back home, those who remained had to contend with greatly-inflated prices on common, necessary items such a food and dry goods. For instance, corn, when it could be obtained, cost $37.50 per bushel. Lard sold for between $7.50 and $8.50 per pound, molasses went for $50 to $60 per gallon, coffee was $12.50 per pound, apples cost between $150 and $200 per bushel and a keg of nails cost between $110 and $130 per keg.

Coin currency nearly went out of circulation, since it was so hard to come by and went so quickly when obtained. As a consequence, many Belfast residents began bartering for goods, a system that helped them cope with their difficult situation.

Although numbers of ships built in Maine boatyards generally decreased because of the war, in 1861, the C.P. Carter Shipyard in Belfast built the gunboat “Penobscot” according to government specifications, in only 90 days, a record time.

The Civil war marked the first time that the news media participated in war reporting in a major way. Belfast home folks were kept up-to-date on war news by daily public readings from telegraph dispatches. Also, the town’s two newspapers, The Republican Journal and The Progressive Age, printed regular news from the front and each week’s issue was greatly anticipated.

The Ladies Aid Society did their part for those going off to war, by making shirts, pants, bandages, quilts and sanitary kits.

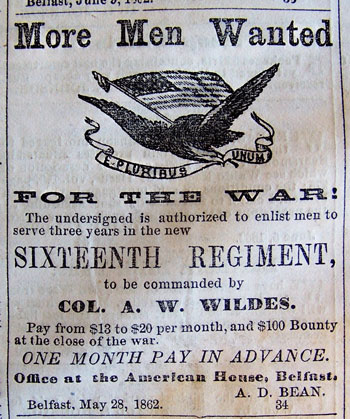

Recruitment posters were commonly seen in cities and small towns during the civil war. The pay and bounty do not seem like much today and were not that much in the 1860’s. For many, going off to war for a few dollars seemed a great adventure. For many it would soon prove otherwise. Belfast Historical Society Photo

Local Excitement

In June, 1864, Isaac Grant, a deserter from a Massachusetts regiment, along with Charles Knowles, who had deserted from the 7th Maine regiment, wounded Belfast police chief Charles O. McKenney in a confrontation. Grant and Knowles had stolen two horses and wagons and this was reported to McKenney. News of his wounding infuriated Belfast people and also, frightened many.

Eventually, Grant and Knowles got into a shootout with the posse that was formed to apprehend them. Grant was hit with a pistol bullet, but fought on until killed with a club. Knowles suffered a fractured skull and died the next day.

The end result of this was that many Belfast residents became frightened to the point where they began carrying guns for self protection. This is reflected in a letter from Frank W. Dickerson to his father. The letter, dated Dec. 5, 1864 and sent from Baltimore, Maryland, read: “I think this war must have fearfully demoralized Belfast from all accounts, at least when peaceable citizens are obliged to keep revolvers for self-protection, a thing unheard of in my day at home. I think your revolver is the first warlike weapon ever introduced by you into the house. I trust you never have occasion to use it.”

Thomaston

The Civil War hit Thomaston hard, especially in the pocketbook. Thomaston experienced its “golden age” in the years from 1800 to 1855. This was a direct result of shipping, shipbuilding and also, a flourishing lime industry. Shipbuilders, ship owners, sea captains and industry chieftains, all depended upon free trade for the maritime industry. Without it, the future would quickly become grim.

From 1840 through 1849, 120 vessels were built at Thomaston. Then, in the five-year period from 1850 to 1859, only about 60 ships were built. The industry took its biggest hit during the 1860-1864 period, with only 18 ships built. After the war, figures rose, but never to anywhere near those historical highs seen during the golden age.

To fully understand the situation, we must inspect the political climate leading up to the war years. The Democrat party was sympathetic to maintaining free maritime trade, thus Thomaston, at the time, was mostly Democrat. This, despite surrounding areas, particularly inland, being staunchly Republican.

Thomaston’s shipping trade depended in a large part, on southern cargos. Many ship owners and ship captains not only knew southern plantation owners, they were friends with them. So it was hard for people from Thomaston to accept or even believe that these same plantation owners were treating their slaves badly.

Just before the war, as tensions escalated between north and south, Confederate privateers hunted United States merchant vessels. When capturing a vessel, the privateers would seize the cargo and burn or scuttle the vessel. Or, perhaps, they would re-purpose it to Confederate use.

And of course, it was unsafe for Union vessels to enter southern ports. But even so, vessels from Thomaston routinely entered southern ports, mostly because of the friendly relations that had always existed up to that point.

But things changed abruptly when, in 1860, the William Singer was overtaken by Confederate port officials in New Orleans and bound over for three months. The captain demanded an explanation and he got it: “We investigated and ascertained that one of the owners of this ship, the person for whom it was named, is a Republican.” Thus Thomaston sustained its first dose of reality regarding the vicissitudes of war.

Then in 1861, Confederates seized three Thomaston vessels. One of these, the General Knox, was refitted to Confederate use; set up with cannons and flying a Confederate flag.

In another incident, the ship Glen Avon was captured with its load of iron on its way back from Glasgow, Scotland. The owner’s wife later related watching the ship burning as she escaped with the crew in a small boat.

In 1863, the Bethia Thayer, another Thomaston ship, was captured by Confederates. But it was released, because its cargo of guano belonged to the Peruvian government. Peru was a neutral nation, so the Bethia Thayer was released.

Attitudes towards the Southern Confederacy changed among Thomaston’s citizens. Unemployment became rampant, with the dramatic downturn of the shipbuilding industry and shipping interests. The people of Thomaston suffered greatly because of the war.

Thomaston, like Belfast and the other towns up and down the coast, experienced a surge of patriotism. A total of 329 men joined the military, both army and navy. This represented 23 percent of the town’s male population given for the year 1860.

Of those who served, 18 died of wounds, 12 from disease and four from being held in Confederate prisons. With the young men just being gone, let alone getting killed, meant that families back home would feel a great burden. Accordingly, Thomaston citizens raised $1,300 for support of families of men gone to war.

Also, Thomaston voted to direct the selectmen to provide basic necessities for the families of volunteers. Doctor Moses Ludwig offered free medical help for these families. The doctor also awarded $100 each to the families of the first 10 volunteers killed in battle.

Naval Surrender

It seems fitting that On May 10, 1865, the Confederate Naval Forces in the waters of Alabama surrendered to Admiral Henry Knox Thatcher. Admiral Thatcher was the grandson of Major General Henry Knox, General George Washington’s chief of artillery during the Revolutionary War. Admiral Knox hailed from Thomaston, the place that hoped, in the beginning, to avoid war and that in the end, gave of so much of its life’s blood and goods.

The Trail

For more information on Belfast, Thomaston and other coastal Maine towns during the Civil War, visit their exhibits and displays. For Belfast, contact the Belfast Historical Society and Museum at 10 Market Street, Belfast, ME 04915, call them at (207) 338-9229 or email them at info@belfastmuseum.org. Or visit their website at www.belfastmuseum.org. Summer hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. and after Labor Day through Columbus Day, Friday and Saturday only, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.

For Thomaston information, contact Thomaston Public Library, 60 Main St., Thomaston, ME 04861, or call (207) 354-4121, for Susan Devlin, coordinator. Contact the library at (207) 354-2453 or email the library at: sdevlin@theartemisgroup.com. Visit their website at: www.thomastonhistorical society.com.

And to learn about activities statewide, contact www.mainecivilwartrail.org.

Hours are 11a.m. to 7 p.m. Monday and Friday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturday.

Many thanks to Susan Devlin of Thomaston and Megan Pinette of Belfast for their kind help in providing data for use in this article.