Rum Runners and the Age of Prohibition

by Tom Seymour

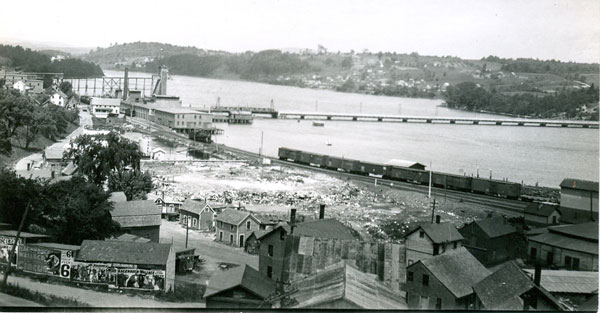

Belfast waterfront in the late 1800’s. The dump in the center of photograph was often picked for bottles to fill with home brew. The city was home to 54 breweries in 1878. Photo courtesy Belfast Historical Society

During the age of prohibition, Mid-Coast and Down East Maine were actively involved in the rum-running trade. Of course rum was only one of the various alcoholic beverages surreptitiously delivered to dozens of ports and harbors up and down the coast. In fact, much of what Mainer’s consumed was grain alcohol, brewed in places like Scotland, shipped to Canada, smuggled into Maine and later cut with water before final distribution.

And while 20th-century prohibition brings to mind visions of organized crime and notorious criminals such as Al Capone, Maine smugglers were not part of that scene. In general, Maine people brought in booze mostly for themselves and friends and neighbors. Many of these small-time rum runners were local heroes and their efforts were appreciated rather than condemned by the local communities.

Early Stirrings

The temperance movement, which was ultimately responsible for national prohibition, came to life in the early 19th- century. In 1813, the Massachusetts Society For The Suppression of Intemperance was formed and Maine, being part of Massachusetts, was part of it.

From that beginning and throughout the 19th- century, various groups took up the temperance banner and well-intended people made it their work to distribute tracts throughout the state. But an actual law prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages (excepting for medicinal or mechanical uses), was a long time coming. In fact, prohibition had several false starts and the years 1844 and 1845 saw the Maine Legislature refuse prohibition petitions.

But determination on the part of the temperance groups finally prevailed and in 1846, Maine officially banned the sale of alcoholic beverages. This was, according to A Brief History of Maine, George J. Varney, 1890, the first law of its kind in the entire nation.

Despite this ground-breaking legislation, the law had no teeth. Penalties were so light that no one took prohibition seriously and the market for booze flourished. Later, another, more effective law was passed. However, despite the large number of Mainers who favored temperance and total prohibition, a great number of people did not at all care for such government interference.

Belfast newspaper cartoon critical of alcohol consumption in the early 1800’s. Courtesy Belfast Historical Society.

In 1855, Neal Dow, Mayor of Portland, Maine and strong temperance man, established an agency for the official distribution of liquors for medicinal and mechanical applications. Dow began purchasing liquor for the new agency to distribute and this was stored in Portland City Hall, from which the agency was to operate from.

But the mayor didn’t have the authority to purchase liquor and a marshal was called to confiscate what by then was known as, “Mayor Dow’s Rum.” The marshal did as directed, and seized the entire stock. But a large crowd had gathered in Market Square, a crowd determined to take the intoxicating liquor for themselves.

The crowd grew and became increasingly more belligerent. Mayor Dow, along with a company of Rifle Guards came upon the scene and ordered the crowd to disperse. When they refused to quit, Dow ordered the guards to fire. That order, much to the credit of the Rifle Guards, was refused. The mayor left at that point, but the crowd by then had become greatly inflamed and rioting began.

An hour after the first confrontation, the mayor, along with a number of the Rifle Guards and also, Captain Roberts, returned to the scene and this time, opened fire upon the crowd, killing a sailor and wounding 10 or 12 others. At that point, the rioters retired. The mayor was later tried and acquitted for giving the order to fire and the “Liquor Agency Riot of Portland,” faded into history. Shortly after this, prohibition in Maine was ended and a liquor license law enacted in its place.

But the temperance movement kept its momentum and ultimately had its way. In 1858 another prohibition law was enacted and this time, it was not simply a political maneuver, but was submitted to popular vote prior to passage. And in 1884, a prohibition amendment was added to the Maine constitution. Maine’s prohibition law remained in place until the repeal of national prohibition in 1933.

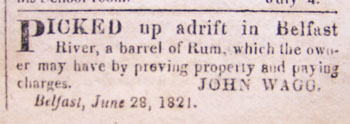

Belfast Republican Journal item from 1821. Courtesy Belfast Historical Society

Underground Distributors

Despite the state law prohibiting the sale of liquor, Mainers continued using alcoholic beverages. Throughout the prohibition years, and particularly during national prohibition (1919-1933), when it became impossible to illegally import alcohol from other states, Maine people became adept at devising ingenious methods of bringing “rum” (a literal and also a generic term for almost any alcoholic beverage) into the state. The Mid-Coast and Down East Regions were hotbeds of smuggling activity and people alive today can harken back to childhood days and recite lively and often humorous tales of the rum runners.

The late Ray Webb, a well-known Maine historian from Prospect, gave presentations on the rum-running days in Waldo and Hancock Counties. The Belfast Historical Society & Museum has footage of one of these sessions held in the mid-1990s. In addition to the speaker, members of the audience, many of them of an age to recall goings-on of the rum-running days themselves, chimed in and added their anecdotes.

According to Ray Webb, alcohol was brought from Newfoundland Canada in to Maine waters on fast (for the day) boats and from there, transferred to smaller vessels and taken ashore. The smaller boats that actually brought liquor to Maine shores had a far greater chance of getting apprehended by the authorities than did the larger boats. In fact, Webb described how these seagoing boats were fitted with airplane engines, making them capable of speeds in excess of 30 knots, far faster than anything that law enforcement had available. Webb said that this situation finally became more equitable when several of these super-fast private vessels were finally captured, putting authorities on equal standing with the rum runners.

Hiding Places

Liquor, often straight alcohol, was transported in wooden barrels and later transferred to metal 1- and 3-gallon metal containers. These resembled the metal cans that present-day solvents come in.

Once safely ashore, the barrels or cans were usually cached in some safe place. This could be anywhere, of course, but wharves and piers were favored. Here, containers were stored on specially-designed ledges beneath the structures. When the time was right, the person or persons who bought the liquor and who were to distribute it locally, had to go through the process of loading the stuff into some sort of wheeled conveyance. But during the interim period, much of the precious liquid disappeared, pilfered by rummaging locals.

When a stash of liquor was found in barrels, thieves would use pod augers, a type of hand drill on a 3- or 4-foot shaft, to drill into the barrel. From there, the liquor was easily drained into whatever containers were at hand. Often, the thieves would not even need to leave their boats in order to gain access to the liquor. Instead, they would just use the length of the pod auger to make a hole and insert a hose or other device in it in order to direct the flow to their cans and bottles.

Some alcohol was brought in in 5-gallon cans rather than barrels and this was a practice of Canadian rum runners. Once emptied, the cans were filled with water and sunk in the harbor and in the case of Belfast, in the Passagassawaukeag River. A Belfast resident, interviewed in 1977, recalled finding lots of these empty cans underwater, when the sun shone on them and made them gleam.

That same man, during the same interview, declined to mention names of anyone involved in rum running, since the families of those involved still lived in the area. That same tight-lipped attitude exists to this day.

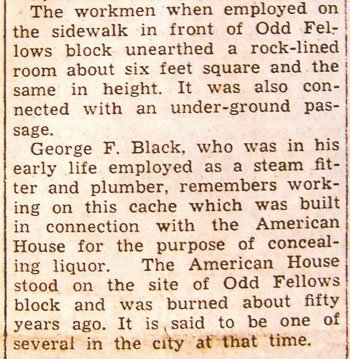

Newspaper clipping from the Belfast Republican Journal. Courtesy Belfast Historical Society

Other hiding places for illicit booze included stone fences, corncribs and even brushpiles. An attendee at one of Ray Webb’s talks mentioned the time that a local man built a huge pile of brush, with the idea of lighting it off at the proper time in order to signal to a liquor-laden boat out in the harbor that it was safe to come in. The man didn’t know that the rum runners had already come ashore with their wares and had hidden them in the brush pile.

In discussing the incident later, the man involved said that the fire burned awfully hot and if anyone were to have looked, they might have seen a grown man weep.

Ray Webb mentioned a humorous anecdote that occurred in a small town in Hancock County. A man had a shipment of liquor coming and worried that his neighbor’s outside light would illuminate his illicit activities. So he went across the street and told his neighbor that “…there will be some traffic tonight and would you mind leaving his light off.”

The neighbor, sensing the nature of the “traffic,” complied. As it turned out, the neighbor’s wife was a strict housekeeper and insisted that her husband leave his work boots outside on the open porch rather than wearing them inside and tracking up her clean floors. That night, the man left his boots outside and when he went to put them on the next morning, found a bottle of liquor in each boot.

Belfast Imbibes

Megan Pinette, of the Belfast Historical Society & Museum, helped this writer greatly in compiling data for this article. Megan scoured the archives, noting interesting and useful facts about Belfast’s liquor consumption in the early days. In one of her notes, Megan said, “One thing I noticed about the Independence Day celebrations is that a great deal of rum was imbibed by all the citizenry of Belfast. By 1802, rum was as plentiful as water and by 1825 there were 54 licensed sellers of liquors. During 1827 the local distillery made 60,150 gallons of rum!”

Megan continued: “During the Temperance movement of the 1830s and 40s the public celebrations were much quieter and tamer. All in all, the people of Belfast relished their freedom from the King of England and knew how to celebrate in fine style.”

While the sale of liquor was banned, Maine law permitted individuals to brew their own beer…providing that alcohol content remained under 3.2 percent. This, quite naturally, became a widespread practice and in Belfast, people picked over the town dump at “Puddledock,” a section of town near the waterfront, for bottles in which to keep their homebrewed product.

These bottles were used over and over, filled and re-filled.

Here is a favorite recipe for home brew, as used during prohibition in Belfast:

One gallon malt

Put in five gallon container (water)

5 pounds of sugar

3 yeast cakes

When you can read a paper through it, it was drinkable.

Local Producers

Not all liquor consumed during prohibition came from outside Maine. Some was locally produced and from an interview with a Belfast old-timer, we learn that, “…bootleggers were everywhere. A Man in Monroe had a still in the woods.”

Another man, a bootlegger, bragged that, “Any liquor you wanted, he could get it.”

Another Belfast man operated a garage. Liquor purchasers would go in and tell him they needed some money. He would tell them to come back later at a certain time. Then, he would sell them whatever they wanted for liquor. He had a large storage area beneath the garage where he stored his liquor.

That same garage owner would go to Bangor to buy his stuff and would load it up in two or three limousines, fitted for that purpose.

Oddly enough, rum runners rarely took their boats up the Penobscot River to Bangor, since Revenue Cutters could easily trap them there. So the product was off-loaded at the coast and driven up to Bangor by auto or truck.

The End

In 1935, two years after the end of prohibition, the first state liquor store opened in Belfast, Maine. A piece in the Republican Journal reported the event: “Liquor Store Open, Does Fair Business. – Belfast’s state liquor store, Number 17, opened as scheduled last Thursday.

…There was no rush of business on the opening day and no one had to wait in order to be waited on. Since then there has been no day with business that could not easily be handled.

“Chief of Police Francis X Pendleton reports no increase in drunkenness on the city streets since the local store opened. Saturday night was one of the most quiet in a long time, he told a Journal representative.”

Kind of makes you wonder what all the fuss was about in the first place, doesn’t it?