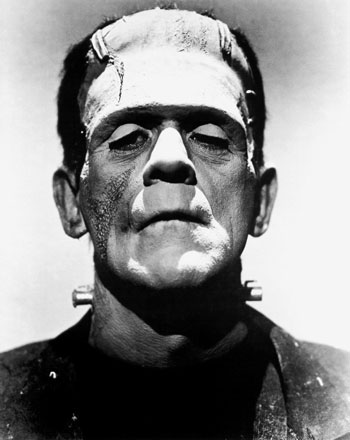

Frankenfish on the Way to Market

On 26 December the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) published notice in the Federal Register of its draft environmental assessment (EA) and preliminary “finding of no significant impact” (FONSI) on AquaBounty Technology’s “AquaAdvantage” genetically-engineered salmon, beginning a 60-day comment period.

This is one of the final steps in a 17-regulatory process for the introduction of the first genetically-modified animal for human consumption. Five day earlier, on the 21st (the pre-release document is at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2012-31118.pdf), the FDA broke the news on its website that it had found “no significant environmental impact” and that the fish would be safe for human consumption. However, in its 145-page report and an accompanying document the FDA said it assessed the environmental impact of the salmon in the United States, not in Canada (where the eggs would originate) or Panama (where the fish are to be reared).

AquaBounty is a Massachusetts-based biotech company. According to the Canadian Press, the company’s “AquaAdvantage” salmon, “developed at Memorial University and the University of Toronto consists of an Atlantic salmon egg that includes genes from chinook salmon and an eel-like fish called the salmon pout…. The genetically engineered salmon grow twice as fast as conventional fish, reducing the rearing period to about 18 months from three years.”

A 24 December Los Angeles Times story reported that “the proposal the company put before the FDA doesn’t involve farming the fish in net pens in the ocean. Instead, fertilized eggs would be created in inland tanks in Canada (on Prince Edward Island) and the eggs would be transported to an inland facility in Panama to reach maturity in tanks. The farmed fish would be 100% female and almost all triploid — meaning they carry three copies of every chromosome in each cell instead of the normal two. That makes them sterile. They would be processed in Panama, and salmon fillets and steaks would then be transported to the U.S.”

Neither the National Marine Fisheries Service (Department of Commerce), nor the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (Department of Interior) were involved in the approval process, although they did submit comments. USFWS “noted that approval would be only for the planned two facilities on Prince Edward Island and in Panama. And it wrote: “Concern for effects on listed Atlantic salmon would arise if there were a detectable probability that the transgenic salmon could interbreed or compete with or consume the listed fish. Given the nature of the facilities described, any of these outcomes appears to be extremely unlikely, and your ‘no effect’ determination seems well supported for approval,’” reported the Los Angeles Times. “But Service also noted that this was based on the farming scheme as currently laid out. If more facilities were planned, or facilities different in kind were planned, or facilities in the United States planned, AquaBounty would have to apply to the FDA each time and the FDA would review any major or moderate changes in plans. The FDA said in the draft environmental assessment that ocean-based pens were a nonstarter because farmed salmon escape from them.”

In 2010, the FDA made its food safety finding, concluding that these genetically-engineered (GE) fish are “as safe as food from conventional salmon, and there is reasonable certainty of no harm from consumption.” The flesh of the fish contain no more growth hormone than regular Atlantic salmon, for example, said the FDA -- a concern of opponents to the fish because of the manner in which they were genetically engineered.

Then, after more than a decade of behind-the-scenes work with AquaBounty, the FDA announced last fall that it intended to approve the biotech company’s application. In response, the public sent over 400,000 comments to the FDA opposing the “Frankenfish” and demanding mandatory labeling of any GE fish approved for sale to US consumers, according to a statement from Earthjustice. The EA finding, announced on the 21st, of “no significant impact,” was the final step for Federal Register publication, but Earthjustice, a conservation law firm, dismissed the EA, saying “concerns are significant enough to warrant a more through environmental impact statement, as required under the National Environmental Policy Act” (NEPA).

Given the gravity of the issue of bringing the first bio-engineered animal to market for human consumption, as well as environmental concerns with the production of these fish, why did the FDA choose to make its announcement during the Christmas holiday? According to Biopolitical Times, the agency was “trying to minimize publicity.” Friday is the best day to publish documents you’d rather not talk about, and the Friday before Christmas (in the midst of a noisy Washington stand-off over taxes) is about as good as it gets. The decision to proceed with an EA, rather than a full-blown Environmental Impact Statement, may, too, have come as a result of pressure put on the agency from an article published on 19 December in Slate.com by Jon Etine. Etine, Executive Director of the pro-genetic engineering NGO, The Center for Genetic Literacy, accused the Obama Administration of playing politics with the application and of scientific dishonesty.

The biotech industry may well have been worried about AquaBounty’s finances. AquaBounty’s salmon, after all, would be the “camel’s nose under the tent” -- the first GE animal approved for human consumption. If AquaBounty went bankrupt, as it was threatening throughout the year, according to various IntraFish articles, FDA approval of GE animals (e.g., the “EcoPig”) might be delayed for years. In May 2012, the New York Times reported that Russian biologist and oligarch, Kakha Bendukidze, invested in AquaBounty helping to keep it afloat, while waiting for federal approval. Through his company, Interexon, he controls 48 percent of AquaBounty. As a result of a bridge loan from Intrexon, AquaBounty CEO Ron Stotish told Intrafish on 19 December, the company was no longer facing bankruptcy in January. That same day Entine’s Slate piece was published and two days later the FDA announced its finding of “no significant impact.” Following the FDA announcement, AquaBounty was able to fend off a take-over bid by Interexon and Entine carried on his rant against the Obama Administration in a 26 December Forbes article, claiming science was on his side.

While much of the concern raised about AquaBounty’s engineered salmon coming to market has focused on possible escapes of these fish into the wild, that is probably more of a long-term fear if these fish gain wide acceptance among salmon farmers, many of whom oppose GE fish.

Although the FDA has found the AquaBounty salmon safe for human consumption, serious concerns remain about how safe these fish really are. Critics of the FDA action say the agency has relied on outdated science and substandard methods for assessing the new fish. “We are deeply concerned that the potential of these fish to cause allergic reactions has not been adequately researched,” Michael Hansen, a scientist at the Consumers Union, told the London Daily Telegraph. “FDA has allowed this fish to move forward based on tests of allergenicity of only six engineered fish, tests that actually did show an increase in allergy-causing potential.” Martha Rosenberg, meanwhile, in a 23 December article in Food Consumer, “More Worries Over Fast-Growning, Genetically Modified Salmon,” ripped the science used by the FDA to get to its conclusion the fish were safe to eat.

What makes matters worse is that the FDA is not requiring the labeling of these fish. Thus it will be impossible for consumers to differentiate in the marketplace between farmed salmon and GE salmon, when it is already hard enough to get labeling regulations enforced to differentiate between wild and farmed salmon. And, to date, no US state yet requires the labeling of genetically engineered foods, although California came close in 2012 with Proposition 37, where the big agricultural and biotech firms spent nearly $50 million to defeat that ballot initiative. A lack of labeling is likely to cause a consumer backlash against all salmon in the market place -- genetically engineered or not -- among the health conscious and those worried about GMOs.

If AquaBounty is successful in the marketplace, it is expected there will be a clamor to rear this fish nearer to their markets in North America and Europe where open-water net cages are the norm for salmon aquaculture. This would then open the door for escapes, and since the FDA does not have the inspection force to ensure that all the GE salmon will all be triploid sterile fish, there is every likelihood for escape and mixing with wild populations. According to the Center for Food Safety’s Andrew Kimbrell, “GE salmon has no socially redeeming value. It’s bad for the consumer, bad for the salmon industry and bad for the environment.”

The FDA is accepting comments on the AquAdvantage® Salmon, either electronic or written, until February 25, 2013. Comments, which should reference Docket No. FDA-2011-N-0899, can be posted via www.regulations.gov, or mailed to: Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305)

Food & Drug Administration

5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061

Rockville, MD 20852.

The Center for Food Safety has prepared the following draft letter template to assist those who will be making comments. That draft letter can be read and downloaded at fishermensvoice.com. See end of Frankenfish story on web version. –PCFFA

For press coverage of the issue, see the 19 December issue of Slate at: www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2012/12/

genetically_modified_salmon_aquadvantage_fda_assessment_is_delayed_possibly.html.