Made in Maine

by Mike Crowe

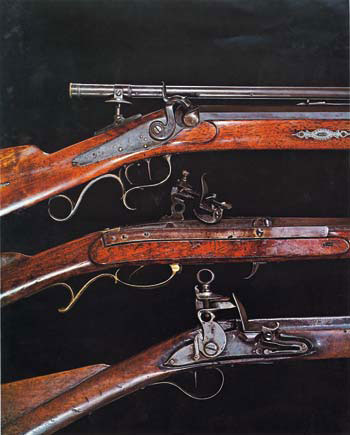

The earliest recorded gunsmith in Maine got started in 1639. Some gunsmiths were also gunmakers and both were needed at a time when it was required that every man own and maintain a firearm. The Maine frontier needed gunsmiths, gunmakers and innovators. Some finely crafted the stock and metal parts, others focused on improving the accuracy. Photo courtesy Paul S. Plumer and the Maine State Museum.

Although Maine has never had a significant gun manufacturing industry like Massachusetts and Connecticut, during the Civil War, Bangor gun maker C.V. Ramsdell produced some of the best rifles used by Union sharpshooters. Master gunmakers like Bill Morrison of Bradford, who built a few precision rifles for competition shooting, was more typical of Maine’s gun making past than the few mass producers in the state.

Maine’s gunsmithing roots can be traced back to the 1600’s when Maine was the colonial frontier. Settlements, English and Indian, were most often established where rivers met the coast. Maine was originally a province of Massachusetts, a state which very early ordered every man to own and maintain a firearm. The constitutional right to bear arms, in fact, has deeper roots with the requirement to bear arms in pre-revolutionary colonial America.

These early colonial flintlocks were relatively simple, but few people had the skills and tools to repair them. Powder and a ball were rammed down the muzzle. The powder was ignited by flint attached to a spring-loaded hammer that created a spark when released by the trigger. It was these metal moving parts that usually needed service. Generally, gunsmiths repaired guns and gunmakers manufactured them, but some did both. Metal-workers, such as blacksmiths and clockmakers, were often gunsmiths as well.

Englishman James Phips arrived in Pemaquid, Maine in 1639 and immediately started a blacksmith and gunsmith business on Phips Pt., just west of Westport Island. Phips is one of the earliest recorded Maine gunsmiths. Although not much is known about his productivity, after he died in 1654 his wife remarried and before she died was known to have given birth to 26 children with her two husbands.

As more fur trading posts were established and more settlers arrived, the demand for gunsmiths grew. Not just among settlers, but among the Indians as well. In the spring of 1751, Benjamin Franklinurged passage of a proposal encouraging a number of sober discreet smiths to reside among the Indians. In 1726, a Penobscot chief lobbied governor Dummer for the establishment of a trading post with a gunsmith at the mouth of the St. Georges River.

British colonial policy regarding firearms and Indian affairs was contradictory, at best. The colonies needed the revenue from the Indian fur trade, so they supported the use of guns by the Indians. At the same time, they restricted the sale of guns to the Indians and in periods of conflict, they confiscated their guns. Teaching Indians to repair their own guns was prohibited, but gunsmiths were sent to trading posts specifically to maintain the Indian’s guns. The French had few restrictions on the sale of guns, and as a result, by the 1650’s northeast Indians were well armed, in fact, by then, dependent on firearms.

The Massachusetts Bay General Court, in 1700, ordered a smith be stationed at the new fort at Falmouth, Maine, to mend the hatchets and firearms of the Indians at a reasonable price. The old fort had been burned by the Indians in 1690.

Hiram Leonard of Bangor, Maine, in hunting garb holding an over and under rifle (probably a Four shooter) and carrying a knife at his chest and an axe in his belt. Photo taken in the 1860’s. Photo courtesy Merritt Hawes.

Compared to the Native American’s bow and arrow, firearms were the weapons of mass destruction of their day. A small breech-loaded swivel cannon of the early 1600’s, on Richmond Island, Casco Bay, in 1632 was commonly referred to as the murderer. Leveling the playing field some, was the Indian skill in military strategy. Colonists learned this from them and used it to great advantage against the British regular army during the American revolution.

John Hall, a Falmouth cooper, became Maine’s first gun manufacturer, after receiving a patent on March 16, 1811. Without previous experience, he dove into the business. His interest in guns had developed while he was a member of the Portland Light Militia, where the focus was marksmanship. The then 30 year old Hall would eventually establish, what was at the time, a major gun making business. One of his significant achievements was to transform the muzzle-loaded gun, (loaded from the end of the barrel) into a breech-loaded gun (loaded near the trigger). Another of his contributions was to the development of interchangeable manufactured parts. For decades he was on a financial tightrope, soliciting government contracts, mortgaging personal properties and hoping a war would create the sales he needed to stay in business.

In December, 1868, fifty years after Hall’s patent, Warren Evans, a Thomaston dentist, received a patent for magazine guns. The Evans Rifle Manufacturing Company became one of the largest gun makers in Maine’s history. Started by brothers, one of them a dentist, the other a skilled mechanic, the company the only mass producer of firearms in 19th century Maine. Like many gun makers, they started with an improvement that they patented. And like other manufacturers, they aimed to sell to state, federal and foreign governments. Their patent for an Improvement in Magazine-Guns was the first of many gun and mechanical patents they received.

Their improvement was a cartridge-advancing screw inside the gun stock. Using the principle of the archimedean screw, in which the threads of a turning screw can be used to move objects along its axis, this advancement moved cartridges to the firing position. The resultant repeating rifle, with a 34-cartridge capacity, was the foundation of their business. They set up shop in Mechanic Falls, near their hometown of Norway, Maine. After finding investors and building the factory, it was on the road to sell the guns. The first Evans rifle is believed to have been made in 1871. However, with the Civil War having recently ended and the U.S. government choosing the Springfield rifle over the Evans proposal in 1873, it was a slow beginning.

Finding enough sales volume was the continuous problem of mass-production manufacturers of firearms. Samuel Colt, of Colt Firearms, in Hartford, Connecticut was always on the road as a super salesman. He came to Maine when it looked like the Aroostook War might develop into armed conflict, in 1839. New Brunswick citizens (with lumber interests) were reported trespassing in Maine. The state was alarmed and allowed a force be sent to the Little Madawaska River, in northern Aroostook. Some of that force was captured and taken to a jail in Fredrickton, New Brunswick, Canada. The Maine governor got congressional authority and support for a militia to defend the border. Colt and gun patent-holder, Mighill Nutting of Portland thought this might be a market for their wares. Colt was actively engaged in politicking, patent claims and legal posturing for a position on what he thought would be a battlefront. It wasn’t, cooler heads prevailed in about a month and Colt was off to the next big thing.

The fact that the Evans guns could fire so many rounds so quickly, had broad appeal. The brothers got General Joshua Chamberlain, Civil War hero and Bowdoin College President, to act as director and company president. The credibility and publicity this gained was furthered by a testimonial from Kit Carson.

While there were domestic sales to sportsmen, a war would make sales boom. With no war at home, sales were made to Turkey and France. The Russians were interested enough to sail a 300-foot rented steamship, manned by the Imperial Russian Navy, into Southwest Harbor in April of 1878 to meet with the Evans. Tensions between Turkey, Russia and Great Britain had the Russians looking for Evans arms. But they did not buy. There were financial troubles at the company that publicity stunts like Kit Carson Jr. shooting a potato off the head of a local doctor in Belfast could not make go away. By the end of 1879, amid positive press, sales were diving, debt rising and the company went under.

More numerous were the inventive small producers like the Peavey brothers of South Montville, Me. One of their patents was for a pocketknife pistol, patented in 1865. With a folding blade, it looked like a knife, but could fire a .22 caliber short round. They also made a pocket sized .22 caliber revolver they called, Little All Right‚ with an 1876 patent.

Guns from the Wild, Wild East

For most of the 1800’s Portland, Maine’s largest city, had many gunsmiths, but Bangor had more gun makers. Gunsmiths had set up shop there in the 1770’s with the establishment of a trading post at Treats Falls. Bangor in the 1830’s and 1840’s was known everywhere as the lumber capitol of the world. It was a rough, bustling river town renowned for its bars, and brothels. Millions of board feet of lumber poured down the Penobscot every spring to waiting lumber ships. There were a lot of hunters and trappers in the woods north of Bangor. But it was the commercial surge created by the lumber business that was something to write home about. Woodcutters and river-drivers, after a winter in the woods roared into Bangor to spend their earnings, as fast and madly as possible. Bangor was the wild, wild east at mid-century.

This boom-town, awash in the cash woodsmen poured into it’s streets, bars and hotels filled with sailors from around the world, became a niche market for a single-shot pistol. The saw-handle, underhammer, percussion boot pistols were a Bangor design. Rivermen liked them because they could be slipped into their boots. William Neal’s style of saw-handle grip was used on many of these simple, inexpensive guns. There was also a demand for a range of guns from ornate presentation pieces to sharpshooters, which were made by several gunmakers.

Twin brothers Andrew and Thomas Jefferson Peavey’s 1866 patent drawing for their .22 caliber short pocket knife pistol didn’t explain exactly how it operated. It has a blade as well as a hammer released by a trigger that extends downward from the handle. The South Montville brothers produced these and later Andrew made a pocket pistol revolver he called the Little All Right. Photo Courtesy Roger Peterson.

If there is a character in the history of Maine gunmaking whose story stood above the high quality of his work, it would have to be Hiram L. Leonard. Born in Sebec, Maine in 1831, he was known as a skilled hunter at an early age. He was soon a famed big-game hunter who supplied lumber camps with moose. Leonard’s exploits as a hunter, a great shot, a man of legendary strength and endurance, and a hunter’s hunter to the Indians might have been reputation enough.

But Leonard was also a highly-regarded gunmaker and inventor. He apprenticed with one of Bangor’s best gunmakers, C.V. Ramsdell, making some unique and good-looking guns. Added to this, his other interests and activities included trapping, dagguerotype, salmon hatchery operation, and taxidermy. Apart from all this, he was in fact, best known and most remembered for, the extraordinary split bamboo fly-fishing rods he made, ultimately with several employees.

Henry Thoreau, on one of his three trips to the Maine woods in the mid 1800’s happened to share a stage coach with Leonard between Bangor and Monson. In his book The Maine Woods Thoreau describes Leonard in the coach crowded with hunters as, “of good height, but not apparently robust, of gentlemanly address and faultless toilet as you might meet on Broadway.

He had a fair complexion, as if he had always lived in the shade, and with his quiet manners might have passed for a divinity student. I was surprised to find out he was probably the chief white hunter in Maine.” The encounter occurred when Leonard was on his way to a commercial hunting trip north of Monson. One of the many anecdotes about Leonard, not a very large man, has him carrying a quarter of moose meat, weighing 135 pounds, between two lakes, a distance of seven miles.

Leonard’s involvement in gunsmithing is more the norm in Maine gunmaking history than the big manufacturing operations. There have been many gunsmiths who repaired firearms, and a few who made relatively small numbers of them.

Currently, Saco Defense Inc. is a mass producer of military arms, which began as a cotton mill machine manufacturer in 1826. In the 1940’s, it started mass military production and, after changing ownership a few times, now produces machine guns and parts for them. Its introduction of quick-change machine gun barrels may be their single most visible improvement. The ability to secure government contracts in a way the Evans brothers were not, at least in part, explains why they are here 125 years after the Evans Rifle Company threw in its hand.

Another mass production machine gun company in Maine is Ordnance Technology, Inc., in Stetson, Maine. Mack Guinn started this company after leaving a company he operated in the 1970’s which developed and produced the Bushmaster rifle. Combining features of the AK-47 and the M-16, this automatic weapon poured out rounds, firing 600 rounds a minute.

The days of firing a musket and reloading by cleaning hot embers out of the barrel with a ramrod, pouring in powder, wad and ball, ramming each down the barrel with a ramrod, to be ready to fire round two are long gone from the battlefield. The company has introduced a magazine for a light-weight machine gun, plastic frames, and in the field, quick change machine gun barrels to deal with overheating.

The number of gunsmiths making and working on flintlock and percussion firearms is on the rise in Maine. Mass producers are making money, but it appears there may be more individual gunmakers hand producing guns in Maine. Black powder shoots and re-enactments are the biggest market for handmade muzzle-loaded firearms. The market cannot compare to the military market, of course, but if the Aroostook War flares up again and they decide to fight it with period weapons, it could be the next big thing.

These photographs appear in Dwight B Demeritt’s book Maine Made Guns and Their Makers 1973 and 1997, published by the Maine State Museum and available at Tilbury House Publishers, Gardiner, Maine. The book is a well researched and written history of gun making in Maine. It is the bible on Maine made guns with 500 illustrations and photographs and a thick bibliography.