B A C K T H E N

Monson Maine Slate

Photo courtesy of Dept. of Speial Collections, Raymond H. Fogler Library, University of Maine

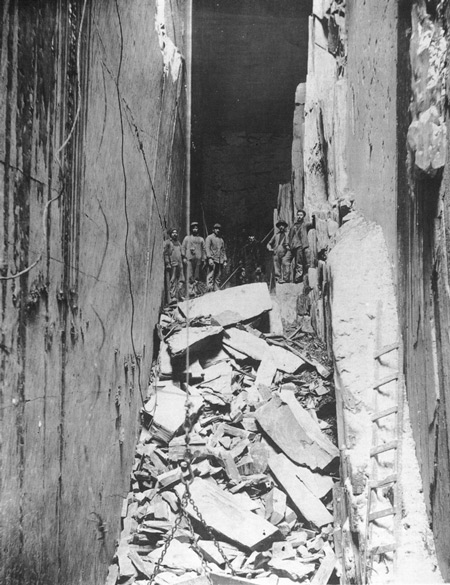

Early 1900s. A “pit” of the Monson Maine Slate Company, Monson.

The first quarry [in Monson] was bought for $75 and inside of three months was sold for $16,000…fortunes were made and lost, companies were formed, operated a while and failed, numerous lawsuits grew out of innumerable disputes and claims, till, about three years ago, the Monson Maine Slate Company was formed…. The company owns a strip of land two and one-half miles long and 250 feet wide…. Imagine a cavity in the earth three or four hundred feet long, sixty wide and a hundred and eighty feet deep. It makes one dizzy to stand near the edge and look down in this chasm….The [Bangor] Industrial Journal, May 10, 1889.

Slate, a “fossil” stone, is nothing more than pure, compressed clay, with the unique tendency to split indefinitely, and a hardness to preserve it from weathering. For a long time it was principally used for roofing, and came to this country mainly from Wales, usually arriving as ballast at nominal shipping rates. Slate industries, dependent on Welsh workers, were eventually developed in Vermont, Maine. Thanks to the “stimulating and strengthening influence of legislation,” i.e., tariffs, Welsh slate was eventually driven from the market.

Piscataquis County is home to Maine’s slate belt. In the early 1800s, settlers worked hearthstones out of slate outcroppings. The discovery in Brownville of slate suitable for roofing was made in the early 1840s by Welshmen who happened to move into the area to farm. Deacon Wilbur of Boston, the country’s largest importer of Welsh slate, recognized the high quality of Maine slate and played an important role in developing the industry at Brownville. Until about 1869, with the arrival of the Bangor and Piscataquis Railroad, all the product had to be teamed thirty-five miles to Bangor by horse and mule team. By 1882 the Monson quarries were producing 32,000 squares, or 800 carloads, annually. Teaming was finally ended with the construction of a five-mile-long connecting narrow-gauge railroad two years later.

The slate belt…stretches…a distance of about 80 miles…. The slate is in veins, set up on edge, between layers of flint, and vary in thickness from the fraction of an inch to 18 to 20 feet…. In opening a pit the sinking is done by blasting among the narrow veins so as to make a working face on the veins thick enough to make slate stock. After a sink is made the slate is removed from the face of the wall by blasting with very light charges of powder which loosens the rock without shattering it. It is then pried off with crowbars and hoisted to the surface by derricks…. The utilization of slate for other purposes than roofing was a matter of slow growth….One of the early articles…was…a butter board…. It was simply a large sheet of slate trimmed by hand and smoothed with a fore plane. They were made by the workmen and sold for a trifle to the farmers’ wives, and upon which they worked and salted their butter…now [specialties are] about as important as the making of roofing slate…. One of the leading specialties made from slate is switchboards for electrical plants, the Maine slate being…[free] from iron and other metallic substances. Probably not less than a thousand different varieties of useful articles are made of slate, among which may be mentioned table tops, laundry and kitchen tubs and sinks, tanks of all kinds, counter tops, urinal stalls, floor tiling, school blackboards, mantels, wainscoting, etc….

The clearing of overburden and hoisting out and disposing of rubbish created huge problems, including landslides. What with blasting, falling rock… and parted hoist ropes, working in the quarries was inherently hazardous. By 1893 the pits were 250 feet deep. As the quarries got deeper, hoisting signals were communicated by beating on a saw blade; when depths reached 400 feet the walls began to bulge inward. About 1915 deep tunneling began at Monson, ending the need to remove waste and the frustrations caused by snow and rain. By the 1930s shafts reached some 900 feet, with workers lowered and hoisted standing on small, unguarded platforms hung on a derrick cable.

Many workers in the finishing sheds, while safe from falling rocks, faced futures shortened or terribly impaired by the insidious effects of silicosis, caused by breathing stone dust.

Daily reports in 1915 from the plant manager at Monson to company president C.N. Fay in Boston were depressing enough to satisfy even a Welshman’s melancholia:

Aug. 4. In (pit) #2 we are taking out that bench of slate we told you wasn’t going to give us anything but rubbish….

Aug. 5. The slate from #1 has a great many joints that cut down on production….

Aug. 7. We are having a regular flood today and had to let the mill men go home….

Aug. 9. Saturday, Sunday, and today makes three days heavy rain, and it is holding up on work.

Aug. 10. Had the piston break on the pump in #1…. Shall have to use a barrel and bail the water till we can get pump repaired.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Days Work, Part 2, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860-1920 , Part II. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, Gardiner, Maine, 800-582-1899.