The King’s Broad Arrow. |

Before long Portsmouth would be the leading mast shipping point for the merchant marine and Royal Navy. The seemingly inexhaustible supply of great masts was soon found to be otherwise. After going inland, the solution for scarcity was in going further eastward. Robert Albion, in Forests and Sea Power wrote, “The quest for lumber settled Maine.” The first water powered sawmill in America was built in Maine at Berwick. Much of the lumber and masts shipped from Portsmouth came from the western part of Maine. Settlers in 1639 reached Cape Elizabeth and had shipped a cargo of lumber to England. Only Indian attacks and the French and Indian War in that century made settlement an on-again-off-again proposition in western Maine.

The single largest increase in demand for great masts was the result of technological advances in warship guns in the mid 1700s. The coking of coal made possible larger and more reliable castings for cannons. Larger guns meant larger ships to carry them. At a time when their naval force was expanding, the British had a dwindling and threatened supply of masts from the Baltic. But only New England had the great masts needed for the larger ships they wanted to build. In addition, the New England masts were lighter, remained more supple and lasted longer than those from Sweden and Denmark.

The volume of wood needed to build these ships helps outline the dimensions of the British appetite for shipbuilding wood. The workhorse ships of the Royal Navy were called third-raters. They had 74 guns, 168' gun decks, a beam of 48' and displaced 1600 tons. It took 2000 oak trees to build one. In a mature oak forest, that is all the timber growing on fifty acres of forested land. Beyond this, spars were needed and 30,000 trunnels, the wood pegs used like spikes to build ships.

The British were literally running out of wood at home. In England their survey of the six crown forests in 1608, which included Sherwood, contained 585,000 tons of timber of suitable quality for the Royal Navy. The survey of 1783, 175 years later, showed 125,000 tons. That year merchant and naval construction consumed 125,000 tons, all the standing timber. In 1791 alone merchant and naval construction totaled 960,000 tons of ship grade wood. Ruling the seas was expensive.

They needed a lot of wood, the colonies had plenty, so the Admiralty set out to lock it up for the Royal Navy.

Regulating the cutting of mast pine was formally instituted by law in 1691. Various legal and political maneuvers were used over the years until the Broad Arrow Act of 1729, which had the most teeth. Reserved trees were marked by three cuts with an ax. The large, prominent inverted “V” was the no trespassing sign of the time. Shaped more like the foot print of a crow, it was called the “king’s broad arrow.” It was a mark long in use on all property of the Royal Navy, including prisoners. The penalty for cutting or being in the possession of even part of one of these trees was a 100-pound fine; a hefty sum for most all but the king’s mast agents. One hundred pounds was what the crown paid for mast pine, but it would not buy all the boards that could be sawn out of that log. The fine was especially tough on the average wood cutter or farmer who profited little from the booming mast trade.

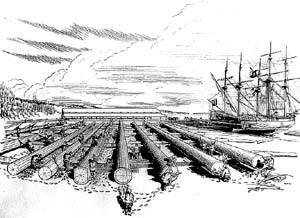

Hewing mast pine to sixteen sides in preparation for loading aboard waiting mast ships. Crews of hewers laid out to the maximum payable dimensions each of the pines brought into the mast depot. They then reduced them to that size with broadaxe and adze. Royal Navy ships would take them to England for final shaping. Copyright S.F. Manning 1977 |

Mast pines were those not on private land and at least 24" in diameter at 12" above the ground. Marked or not, they were not to be cut. For a mast pine to be selected for cutting there were other criteria. These trees had to be virgin growth, which gave them tighter ring spacing and greater strength. They had to be straight and clear of branch growth to a height in proportion to width. A 24" diameter tree would have to be clear to about 50' and a 54" diameter tree was clear to 110'. The largest on record varies some depending on the source – from the 54" tree above to 7' 8" across the butt. An overall height of 250' was recorded in a 1760 publication by William Douglass. They grew close together, competing for sunlight, for centuries – no metal cutting tools, no king’s cannon.

There were a lot of these trees, lots. The giant mast pine was the sequoia of the Northeast. They stood above the smaller, though none the less mast pine, that surrounded them in a dense thicket of old growth timber. In the years of the Broad Arrow laws, 1691 to the Revolution in 1776, less than 5,000 of these logs were delivered to the Royal Navy. The crown sought to control more than supply with the Broad Arrow policy; they also wanted to control price. Though the colonists were Englishmen at the time, they also knew of the huge timber resource they lived in. For many cutting wood was their livelihood.

Sam Manning, in his book on New England mast pine called the 17th century economy a “wooden economy.” He likened the importance of wood in the 17th century to the importance of oil in the 20th century. Almost everything was made of wood – buildings, ships, vehicles, containers, fuel, basic machinery and tools. The colonists had lived for years under relaxed English rule and had sawn lumber for many more. When masting profits rose and agent greed along with it, regulation was tightened. But with few of the king’s men in the field, getting around the law was not difficult.

The records of domestic American export of clear woodstock, boards, clapboards, staves, deals, etc., exceeds the Royal Navy deliveries by 1000 to 1. There were more markets and more profits. Skirting the regulation was not cheating, but just the way business was and had been done. There were lots of trees, woodcutters everywhere and few Royal foresters to protect the resource. The life and business of the New England colonies had become less connected to that of the Crown’s while England built its maritime based empire.

Samuel F. Manning, boat builder, illustrator, historian and mid-coast resident has written a good book on the New England mast pine. In addition to covering the history surrounding the subject, the book contains his illustrations of how masting was done, from marking with the broad arrow to loading the mast ships. The illustrations provide scale to an operation difficult to imagine with the pines known to contemporary New England.

Fishermen’s Voice would like to thank Sam Manning for the use of his book and his illustrations in the preparation of this article.

New England Masts and the King’s Broad Arrow, 1979. Thomas Murphy, publisher, Kennebunk, Maine 04043.

|