|

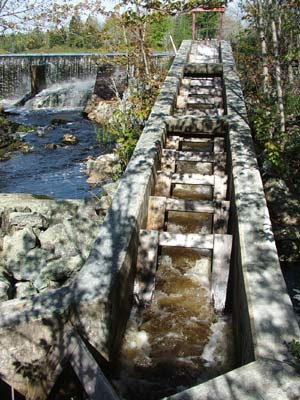

Fish ladders allow fish access around dams. However, if ladders are not maintained the fish cannot pass. Debris can blocking passage, and disintegrated wooden steps are two common ways they become useless as passages for fish. Other than lifting buckets of fish over the dam by hand or removing the dam there are not alternatives. Photo:Fishermen's Voice

|

Alewives have always poured into streams along the Maine coast headed for fresh water ponds to spawn. They come in from the ocean in early April, find their way to the ponds they were born in, spawn and leave. By mid July their small offspring will also head down stream to the ocean. In five years they, too, will return to that same stream and head for that same pond to spawn.

Native Americans caught them, and later Europeans. It was once, and not that long ago, a major seasonal fishery. The bottoms of streams were black, covered with the backs of alewives packed in, waiting to make their way around and over rocks and obstacles.

Today licensed alewife fishermen take considerably smaller numbers of alewives from select streams. Many things changed the once massive spring surge of alewives into Maine streams. Industrial era dams blocked their passage. Fish ways built to let the fish into the ponds above didn’t always work as planned, and many were not maintained. Beaver dams also block the passage of alewives.

Another impact on the alewife population recently has been increased predation by stripers. Some ponds have had pickerel introduced into them, and those feed heavily on young alewives.

Streams that were fished too heavily, leave too few to spawn and reduced returnees. The old regulations required a 24-hour period, weekly, to let the fish pass. Today they must be allowed to pass between 6pm Thursday and 6 pm Sunday.

The DMR recently changed the percentage of the stream that can be closed off to the passage of fish. The increased demand for alewives is almost certain with the pressure from trawlers on herring. Other herring markets like aquaculture feed, human consumption and “zoo food” are competing with the bait markets. The recent scientific recognition that the predator fish which survive on herring will need to be considered in the equation that measures total allowable catch will have an as yet undetermined impact.

Brad Parrot, a licensed fisherman from Sullivan, has restored a Sullivan stream to productivity. He recalled recently, that the same stream yielded truck loads of alewives just 30 years ago. On another alewife stream he said he has hauled more alewives over a dam to the pond than he has taken out. Parrat is one of a small number of fishermen working the alewife fishery today.

Chad Parrat of Sullivan, ME with a dip standing near the 10'x4'x5' enclosure used to trap alewives on the way upstream to Flanders pond. Parrat improved access to the spawning pond for the alewives over the last five years. A licensed fisherman, he contracts with the town to fishing alewives in the spring run. Photo:Fishermen's Voice

|

Lobstermen use the alewives for bait. The change of bait, they say, attracts more and larger lobster. It is also a tougher flesh and lasts longer in the bait bag. Before herring became the dominant lobster bait, alewives, river herring and redfish were also used.

Pollution in many rivers and streams was bad enough in the 1960’s that fish didn’t return. Industrial fishing ships continue to take alewives offshore, mixing them with their near relative the targeted herring. River herring, or bluebacks, are another anadromous fish and close relative. River herring come into rivers to spawn. They do not travel to ponds, but spawn in the rivers. River herring populations are down, and it is believed in part, from being taken offshore by industrial trawlers targeting herring. Processors think of it as protein and cut it up for aquaculture feed or zoo food and freeze it.

Parrot has been alewife fishing for five years. He has a contract with the town to harvest the alewives. This is the traditional practice. Towns contract with specific fishermen to harvest the alewives coming up the streams in their towns. Some towns have put moratoriums on alewife fishing. Some, like Blue Hill, for fifteen years in an effort to let their stocks rebuild.

The Sullivan stream that Parrot fishes required him to remove several beaver dams and provide easy access for the fish for several seasons before taking any. He believes that stewardship of the stream and letting enough fish pass to spawn will restore the productivity of the stream to what once was. He estimates four to six fish return to spawn for every one that makes it to the pond above.

Hauling alewives from enclosure. With a net across stream, alewives are sent imto pen and gates are then closed. Alewives must be allowed to pass from Thursday at 6 pm to Sunday at 6 pm. Parrat’s goal is to restore the stream to productivity levels of the 1970’s. Photo:Brad Parrat

|

Using nets in the stream to guide fish through an enclosure on their way upstream Parrot can close off that enclosure to harvest fish. On the way back down stream fish are guided around the enclosure by nets in the stream. Fishermen come to his fishing spots and buy directly from him.

This method of fishing with the focus on this specific fish, at a particular age and the ability to regulate how many pass, dramatically contrasts with the factory ships that indiscriminately sweep up all ages of fish and many different kinds in enormous tows.

Concerns about possible herring bait shortages has some people looking at other bait sources. Among the options is alewives. In response, the state has made changes in some of the alewife fishing regulations. They are also taking over the restocking of some ponds.

|