B A C K T H E N

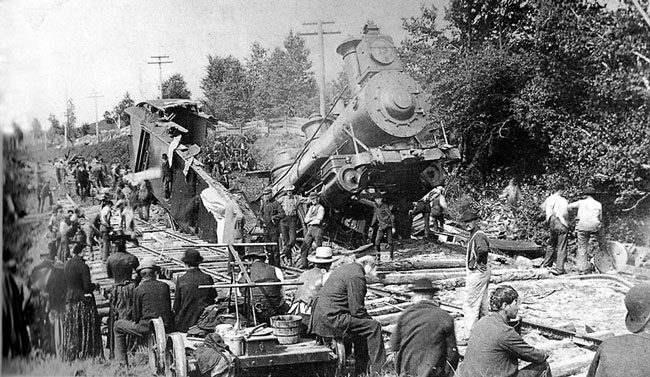

Maine Central Train No. 13

Maine Central train No. 13, pulled by engine 45, wrecked by a washout at Crowell’s Brook, west of Oakland. The accident happened at 4:00 p.m., June 10, 1889. This photo was evidently taken the following morning, after the cars had been hauled off. Newly laid track, crossing the brook on cribwork, bypasses the wreckage. The crash-worthiness of wooden rail cars is only too obvious.

Photo provided by William H. Bunting

Engineer William Underwood set the brakes but could not stop the train in time. Thrown from the demolished cab, he was floating away, insensible, when saved by the newsboy, Arthur Smith. Roscoe Stevens, express messenger in the splintered mail car, had both of his legs crushed. One had to be amputated above the knee, at the site, and it was reported that he bore the operation manfully. All three mail clerks and the fireman were badly injured, although the Kennebec Journal confidently declared that none would die.

Injury and destruction aside, there is a bucolic innocence to this scene, as the simple townsfolk gather to enjoy their train wreck. No police lines or officious walkie-talkie people intrude upon their pleasure. But whether their lives were really any simpler than our own is debatable; it certainly wasn’t for Roscoe Stevens. Fortunately, any doctor from a hive of industry like Oakland—which was alive with maiming belts and shafts, exploding grindstones, and mindless triphammers—was probably a quick and efficient “sawbones.” Hopefully he believed in microbes, washed his hands before he operated, and was determined to break the old habit of honing his scalpel on the sole of his shoe.

Certainly there was nothing simple about managing a rapidly growing railroad like the Maine Central. By 1889 the company operated on 650 miles of track, and also ran a steamboat line. Regular daily traffic included 85 passenger trains and 46 freights, powered by a stable of 119 locomotives. New general offices in Portland were located next door to the magnificent new Union Station, shared with the Boston and Maine, the Maine Central’s controlling owner.

Railroad workers were likened to disciplined soldiers, and certainly much of railroading was as tedious, if far more exacting, as life within the ranks. With 167 stations, the Maine Central’s ticket department dealt with 30,000 possible combinations for regular business, along with excursions, special rates, and so on. All tickets were returned to the central office to be compared with records submitted by the station managers. Many tickets involved travel over various lines, with each road to be credited proportionally.

Freight agents were responsible for tracking the movement of every car in the system, including those belonging to other railroads. (Monthly records were sent to a Boston clearing house, where 150 clerks figured out who owed what to whom.) The monthly movement of Maine Central freight cars totaled 1.5 million miles.

The making of timetables, and the running of trains—two especially critical tasks on a single-track road without automatic signaling—was the job of the train dispatcher’s office. Traffic was ordered and monitored by telegraph. No train could move without a written order, hundreds being issued every day.

Maintenance of way, concerning the upkeep of track, buildings, bridges and culverts, was the responsibility of the chief engineer. A great vault in his office held all the deeds of the railroad, and drawings of all its structures. Other departments were responsible for maintaining locomotives, maintaining cars, paying the 2,500 to 3,000 employees (after about 1898 employees along the lines received cash from a pay car) keeping the books, purchasing, and so on. For every hand that gripped the throttle, many more clasped the pen.

The lunch buckets of members of the wrecking crew sit on the hand car. Telegraph poles, and fence intended to keep livestock off the track, appear in the background. Maintaining fences, which were frequently burned by train-ignited fires, was a large item of expense in dry years.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Day’s Work, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860-1920, Part I. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, Gardiner, Maine, 800-582-1899