The scale of the problem include impacts such as increased pavement runoff, agricultural fertilizers and chemicals, phosphates, lawn chemicals, sewage treatment plant effluent, pesticide spraying programs for insects, etc. Unknown, are the affect of all these components mixed together, combined with rising water temperatures from global warming.

Pat White, recently retired President of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association said, “The water quality problem makes fisheries management problems look easy.”

Grand Manan lobsterman Lawrence Cook said, “We are extremely concerned with water quality.” He referred to ciber methrin, a chemical formerly used in salmon farms to kill sea lice, and which is also lethal to lobsters. Canada’s large, farmed salmon industry and its management are a focus of concern for lobstermen in Canada.

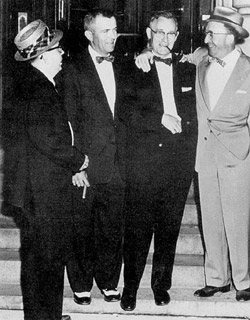

Low prices paid for lobster in the 1950s resulted in legal action against both buyers and fishermen. Basically, both sides lost the case in court in what is known as the “lobster war”. But, the fishermen had learned to get together and organize for their industry. They thereby won in the long run. Left to right: John Knight, Rodney Cushing, Leslie Dyer (Maine Lobstermen’s Association President), and Alan Grossman, the group’s lawyer at the federal courthouse in Portland. Photo: Courtesy of Barry Faber. The Great Lobster War by Ron Formisano, University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA |

“Dana Rice, a Gouldsboro lobster dealer and active participant in fisheries issues said, “There is not a lot of scientific data on it (water quality in the Gulf of Maine), but the fishermen are worried because they are out there and they see the changes. They see that species are not around where they once saw them—near shore and in the rivers.”

“Fishermen see these developments along the shoreline, “ Rice said. They know how the use of lawn chemicals and increased square yards of pavement increases toxic runoff. It was pointed out that the same pesticides used on various insects, for things like the West Nile virus, also kill lobster.

Harpswell was mentioned as having an effective set back for spraying chemicals for the brown moth that effect chitin production in lobster shell. Frustrated by the lack of significant movement on the issue, Bar Harbor lobsterman John Carter said, “We started talking about it two years ago and we are still talking about it. We are not managing it, but it is managing us.”

Bonny Spinazzola responded by saying, “Since we are talking about triggers [lobster mortality, etc.] why can’t we have triggers that bring in other elements such as pollution, dogfish, etcetera?”

Kittery Point lobsterman, Dave Kaslowski said the state of New Hampshire plans to run a large sewer line down the middle of the Piscataquis River and out to the bay islands. After referencing the problems in Long Island Sound, New York, he asked the group, “How are you going to stop the pollution?”

Jim Bartlett of Beverly, MA, said, “We have the pipe and there’s no more fishing. As soon as Kittery gets the pipe, you’re done. Big business is involved and you can’t fight.”

More than any single comment made, the fact that a unified position on water quality was presented by fishermen from St. John’s, Newfoundland to Hell’s Gate, led Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association executive director Bill Adler to observe that it is a “major shift for lobstermen to say that external forces can impact the fishery.” Adler also mentioned the major difficulties in organizing (fishermen) in order to help them better address problems in their industry.

Reporting

While water quality was a concern, mandatory reporting of landings was a heated “issue.” Mandatory reporting was a topic that raised many negative comments. However, the demands for better data to describe the condition of the fishery, from both scientists and fishermen, may drive the likelihood of some form of landings recording in Maine.

In outlining the position of Downeast fishermen, John Carter said, “They don’t want reporting. People (Downeast) are scared to death of scientists and scared to death of managers because of the threat to their way of life.”

“In Maine, most lobstermen don’t know this meeting is on. They get up in the morning and if there’s no wind, they go out. If it’s windy, they go to their shop,” Carter said.

Regarding reporting as giving up pieces of control over fishing, Carter referred to Canadian Ashton Spinney, who told him to “be careful when you give something up, because it doesn’t come back.” But concerns about revealing traditionally guarded catch information, taxation issues and the extra work recording landings also surfaced as reasons to object. Part of the problem for some, said Dana Rice, “is that they have been beat down by the government in the past.”

An example of this mistrust fishermen have for management is the old model used for the stock assessment. That model, the so-called Leary model, had been developed for predicting agricultural crop production. The use of that model for the fisheries assessment predicted a lobster stock collapse. The fishermen said it was “wrong and nuts” but they could not convince management.

More recently, Yeng Chen, a scientist at the University of Maine at Orono, developed a new model that takes into account more data. That new model was used in the 2005 lobster stock assessment, which has shown the GOM lobster stock to be in good shape.

However far apart the two sides are on reporting they are much closer to agreeing on the need for more data, though positions on the data varied.

Casco Bay fisherman Steve Trane said, “What management does with the data is what scares me. Fishermen fear the data will come back to bite them.”

Lawrence Cook of Grand Manan said, “How much weight can be put on it [the stock assessment] since the amount studied is so tiny?” Cook said, “If data suggested something were wrong with the resource, and the assessment indicated it, the lobstermen would suffer the consequences. However, if that problem with the resource were external impacts, such as chemical contamination, lobstermen would be wrongly accused.” The observation was met with applause.

There was general agreement that a correct assessment needs more data, but at the same time, some division over what sources and what means assessors should use. However, both fishermen and managers agreed that more and better data could serve everyone. Bonny Spinazzola of the Atlantic Offshore Lobstermen’s Association said, “We want to know what’s wrong with the resource, because we want to fix it, because we depend on it.”

The demand for data appears to be driving the demand for mandatory reporting. Maine, the last state without it, is likely to have some form of mandatory reporting voted in on May 10, at the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Committee spring meeting in VA, according to Terry Stockwell at the Maine DMR. Pressure from the other states with mandatory reporting are influencing the decision making process.

Rights

There are those who see mandatory reporting as a loss of rights that may lead to a stronger resource. But others see the inability to catch fish that are eating young lobster and other recovering fish stocks as loss of rights resulting from a flawed management plan.

“If or when the lobsters are gone, will we be allowed to catch cod?” one fisherman asked.

Most objections on this issue focused on dogfish. Several fishermen said some areas off Massachusetts are thick with dogfish. They eat cod, lobster and strippers, and they are protected. Fishermen reported more and more cod coming up in their traps, but they cannot keep them. These predators on lobster stocks are being seen as an immediate threat to what the recent lobster stock assessment described as healthy.

Several fishermen said that a broader view of what impacts the lobster fishery is needed; a position that is seen, if indirectly, as supporting data collection.

At the end of the day, attendees discussed adequate and responsive funding systems for scientific research. In response to fishermen who said there was a need for more research in some areas, Carl Wilson, a Maine DMR scientist said, “Maine has a $300 million dollar fishing industry, yet we [scientists] have to go out all the time to find money for a couple of sea samples.”

Dana Rice thought Maine has made some progress in this area. But, added, “with a fee of $50 or $75 on a license paid to dedicated funds for science” a source of funding would be available.

The federal system of funding is complicated and slow. Reserves, however, could fund research that fishermen think needs to be done in a timely fashion. There is some money available now from motor vehicle license plate fees, etc., but a dedicated fund for research would offer flexibility and a more rapid response that is seen to be lacking in the current system.

Brad Young of St. Johns, Newfoundland said, “We need to form large groups, get away from individuals looking for more fish in Washington, etcetera.”

This sentiment was reflected by Kenny Drake of Prince Edward Island who said, “The Canadian Federal Department of Fisheries failed in all species. When they told us we were getting regulations whether we want them or not, we got our own research, looked at past data, looked at provincial fisheries and got help analyzing fisheries.”

Dana Rice said, “These meetings were intended to demonstrate the collective power we do have.”

Ted Hoskins of the Maine Seacoast Mission and moderator of the event responded by asking, “How do we marshal the power to implement it?”

|