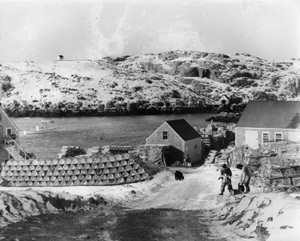

Monhegan, 1978. Not only a tight knit community as fishermen, but residents of a small island. The combination illustrates the capacity for self-regulation and oversight of the resource they protect with a winter lobster season. Photo: Cathleen Carreirot |

Lobster prices dipped just before Christmas, and that was unwelcome, he said. Thirteen boats are fishing for lobster this winter, and the trap limit is 600 each. Cundy said, “we’re crowded on the edges” by bigger, faster lobster boats from the mainland.

But he acknowledged the 1998 legislative act establishing Monhegan’s territorial fishing area was a good thing, giving islanders more than they had before. The zone was created after friction with Friendship lobstermen who were said to be invading Monhegan’s traditional fishing grounds.

The law spelled out an unwritten understanding, setting a two-mile limit around the island.

When the island’s warm-weather population swells into the hundreds with day-trippers, hotel guests, artists and seasonal residents, lobstermen find other things to do. “Everyone can find work in the summer. They go carpentering and seining and tuna fishing; some of them work for bed and breakfasts.”

Cundy worked for decades with wooden traps, which had to be mended or replaced in the off-season. “I just got so I could build a good one, and the wire traps came along,” he quipped.

He hasn’t yielded to fiberglass boats. He still favors a wooden boat, and these days he operates a 36-footer. Lisa Brackett from New Harbor is his sternman, and she does a fine job, he said.

Cundy started fishing in 1953, practically living on seiners in the days when fish were plentiful. He fished with Captain Manville Davis for pogies, mackerel and herring.

Monhegan, 1978. One of, and possibly “the” earliest settlement by Europeans, Monhegan remains unique in many ways. The fishing community has roots to the very early European fishing stations in North America and the American Indians before them. It’s lobster resource management is both unique and senior among Maine plans. Photo: Cathleen Carreirot |

He remembers when “you could row down the harbor, drop a line over the side and catch a cod.”

“If I was a young man, I don’t know as I’d want to go fishing. You look out on the water…except for the lobstering, it’s dead.”

An 1886 Maine gazetteer says 1,000-acre Monhegan Island was a fishing port for Europeans since the early 1600s, and was used by Native Americans before that. The population in 1870 was about 165; by 1883 it had fallen to 133.

The 1886 record says, “Potatoes are the chief crop, and fishing the principal occupation of the islanders.” Today, tourism is probably the chief enterprise, while lobstering still supports many of the year-rounders.

The bigger lodges are the Island Inn, Monhegan House and Trailing Yew. Outside of the small village, which includes early 19th century homes, most of the island is permanently protected by Monhegan Associates, a group set up 53 years ago by summer resident Ted Edison to preserve the natural beauty and “simple, friendly way of life.” Seventeen miles of trails circle and crisscross the island.

For years Monhegan was over-grazed by deer. Then in 1997, with the threat of deer ticks, a sharpshooter was hired to kill off the herd. Another threat, according to a University of Maine report, is proliferation of barberry, a prickly invasive species.

Because the deer didn’t eat it, the barberry was free to overtake native vegetation.

Over the years, islanders have banded together in good times and bad, and figured out how to deal with their problems. Those who choose to live on Monhegan, even for part of the year, tend to be fiercely loyal to this rocky outcropping in the sea.

Cundy’s wife Barbara lives in Boothbay Harbor, avoiding the family’s drafty house on Monhegan during the colder months. She has worked for years at the Fishermen’s Wharf Inn at Boothbay Harbor. Daughter Donna is a Monhegan islander, working as an artist and a teacher’s aide in the one-room school.

“Island life is rugged work,” Don Cundy said. “You’re always lugging something.”

|