B A C K T H E N

Androscoggin Railroad

Photo courtesy of Maine Historic Preservation Commission

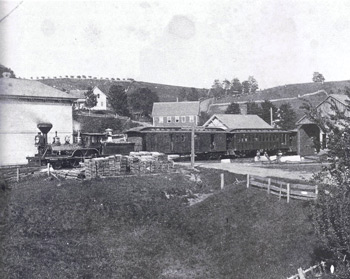

The Androscoggin Railroad’s locomotive Leeds, taking on water at the Depot Street station. Livermore Falls, probably in 1872. Built at Manchester, New Hampshire, in 1852. the Leeds became half of the road’s motive power when the Dr. Garcelon was repossessed. Running boards provided for the fireman’s trips forward to close the cylinder petcocks and pour tallow lubricant into the cups. The white building housed the water tank, no doubt filled by hand-pumping.

The charms of this scene, with its glinting brass, lazying boys, hilltop apple orchard, and bundles of sweet-smelling shingles, would have been lost on grieving former stockholders. Chartered in 1848, the road was supposed to have thrived by tapping a region filled to bursting with firewood, ship timber, fat cattle, and luxuriant sheep. The route presented no great difficulties, the stock was said to be a certain sellout. In fact, following the standard scenario, costs were underestimated and income overestimated. Meandering slowly northward from its connection at Leeds with the broad-gauged Androscoggin and Kennebec, the road finally reached Farmington in 1859.

The railroad lacked a great deal. For want of a snow “plough,” marooned passengers begged farmers for food. For want of pay, employees were impoverished – the 1860 annual report explained that “the mental condition of the former Treasurer...had rendered him unable to prepare a Report, or to leave the books and papers of the office in so desirable a state as he otherwise would have done.” For want of a sand dome, a locomotive stalled in the middle of old Aunt Fabyan’s farm. The railroad owed Aunt Fabyan for runover sheep, and after an engineer squirted hot water at her, she larded the tracks. The engineer raved, smoke billowed, sparks flew, and the driving wheels spun like “a paring machine gone berserk.”

In general, the road’s relationship with farmers on its right of way was not good. The ruling establishing railroads’ responsibility for fencing livestock out– the general law required fencing livestock in – came at the road’s expense. Engineers were annoyed by having to stop for farmers’ barways; J.C. Stinchfield was riding a construction train when engineer Littlefield drove briskly through a barway of farmer Solomon Lothrup. A flying bar landed amongst the men riding on a platform car being pushed ahead, causing much excitement, “which pleased Mr. Littlefield very much.” C. W. Willis recalled an engineer in the ’60s who, one night, having drunk some whiskey, announced to his crew that he would personally attend to taking down all the barways. This he did, as fast as he could, leaving a trail of spark-ignited stump fences, and bar-strewn pastures from Farmington to Leeds.

This was the era of trial-and-error railroading; engineer John Kaufer was fearfully and fatally scalded when he thawed a frozen petcock by blowing in it.

In 1860 Bath investors took control and built a standard-gauge link from the Portland and Kennebec at Brunswick. To beat an injunction sought by the Androscoggin and Kennebec, the Androscoggin narrowed itself on a Sunday, but remained hopelessly in debt, operating seized trains over seized track.

In 1871 the Maine Central took control, gaining a road so full of “humps” and “cellars” that the top of the locomotive’s stack was often lost sight of from the caboose monitor. Engineers went into cellars with the throttle open, while conductors braked their caboose to keep the cards from bunching up and then breaking apart on the way out.

Turned loose on the main line, Androscoggin engineers became terrors. Bearded Cy Hall was confined to the little Sandy River for slatting off steam domes. Jovial Al Kilgore, his locomotive customarily bedecked with feathers, wool, and blood, once killed fifty-nine out of sixty tie-counting sheep. Dashing handlebarred Hartland Foss was tapped to pull the private car of General Manager Payson Tucker, and when word was telegraphed that Tucker and Foss were inspecting track, no section boss dared put a handcar on the rails until the Livermore went thundering by.

A disaster to investors, the Androscoggin was a practical success, and was key to developing the great water powers of Livermore Falls. Promoter Captain Ezekiel Treat lost a fortune in railroad stock, but gained a far greater one selling real estate. Regrettably, the loss of his father, a retired sea captain killed by a locomotive when the mare he was driving stopped to look back at her colt, could not be recouped.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Day’s Work, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860-1920, Part I. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, Gardiner, Maine, 800-582-1899