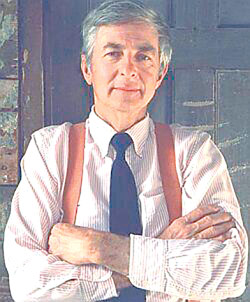

The Humble Farmer, Robert Skoglund, produced a weekly MPBN evening radio show for 28 years. Asked if he is a St. George native he said,“I live less than a mile from where my great great great grandfather Samuel Gilchrest, who was one of the Insurgents fighting alongside of George Washington, is buried.” Photo courtesy of Robert Skoglund The Humble Farmer, Robert Skoglund, produced a weekly MPBN evening radio show for 28 years. Asked if he is a St. George native he said,“I live less than a mile from where my great great great grandfather Samuel Gilchrest, who was one of the Insurgents fighting alongside of George Washington, is buried.” Photo courtesy of Robert Skoglund

|

Mock Maine products and concepts seem to breed like insects. There appears to be no end to the marketing plans “Maine” can be attached to. The 1980s TV program “Murder She Wrote,” set in Maine but built in a Hollywood basement, was apparently Maine, in the minds of some mid-westerners. Towns like Boothbay Harbor have been transformed, and now look like these manufactured TV images. Architects have plopped down hundreds of second homes along the coast. The owners apparently think these look like “Maine homes.”

The Humble Farmer, on the other hand, is possibly the most genuine article “Maine” in the public arena. For 28 years St. George native and resident Robert Skoglund produced The Humble Farmer, a weekly evening radio show on the Maine Public Radio Network.

The show has been humor, dry New England wit, jazz music from the 1920s through the 1940s, history, letters from far flung fans, odd snippets of news, obtuse observations, politics, philosophy, and wonderings. All this combined in a way that felt casual, as casual as a conversation with an old friend toward the end of the day. One thing segued into another, with links apparent and otherwise, and humor the framework for every broadcast.

Skoglund’s political insight, directness, and wit are in the tradition of Thomas Paine, Ben Franklin, Will Rogers and Jon Stewart.

Humble, as he is known on the air, and off to some, uses story-based humor. Long the standard before late night television established the one liner. The following is an example of a Humble joke. Skoglund borrowed it from the late Maine writer and humorist John Gould.

“When the minister came over to Winky’s farm, he did what clergy always do: He tried to say something good about everything. “Nice looking cow you have there.”

“Thank you, sir. Thank you.” “Nice looking chickens.” “Thank you, sir.” “That’s a nice looking ass you have over there.” And Winky turned all red, and hid his face in his hands. The minister looked surprised and said, “What’s the matter with you? Have you not read the scripture? Did not our savior ride into town on the back of an ass? There is nothing wrong with that word, and don’t you blush when you hear someone use it. And I don’t want you to refrain from using it.”

Winky took all this to heart. The next time the minister came to call, the animal had died, and Winky was out in the field with a shovel in his hands burying it. The minister walked up to Winky and said, “Hi, what are you digging there, a post hole?”

Kennebunk English teacher Olga Skorapa, said, “I liked the hokey, down-home Maine quality of the show, but at the same time it was intellectual. It is a unique part of Maine, and he (Skoglund) represents us. I listened to the show for 30 years, and emailed many letters, some of which he read on the air.”

Skoglund was asked recently to write an obituary for Andrew Wyeth, the artist who lived near the Maine coastal town where Skoglund grew up. The form was not what might be expected in an obituary. It was in the form of a story with anecdotes and several characters, describing the internationally known Wyeth’s life among the people of the community. Skoglund said he did not know Wyeth, but had met him. He did know many of the people who knew Wyeth, including those non-relatives who called him Uncle Andy.

Toward the end of the obituary he wrote, “I'm sorry, but I can’t stop until I tell you something else Andy did for me. One day he was talking with Carol in the post office. He had a magazine called Art and Antiques in his hand and right there on the cover was a picture he had painted of one of our neighbors. Of course, by then I knew who Andy was. When I was 15 and first ran into him down on the river he was quite surprised that I had never heard of him. Anyway, he gave me the magazine and when I got home I saw a picture in there of Bruce Stanley, another neighbor who lived down the road. Back then you always saw Bruce Stanley dressed in the most wretched clothes imaginable. He had long, stringy hair and mutton chops, and of course you couldn't walk around town like that for too long before Andy'd ask if he could paint you.”

“That was back when we were trying to enact a seatbelt law in Maine and I had been asked to make a television commercial promoting the use of seat belts. So I hired Smith and Atwood, who were the top camera guys in Portland, and got Bruce to sit on a lobster crate down on that dock Sonny used to own in Tenants Harbor. Bruce just sat on that lobster crate, looking just like he did in that painting of Andy’s and didn’t move – while I said, “This is Bruce Stanley who lives here in Tenants Harbor. Last year a terrible thing happened to Bruce. Andy Wyeth painted a picture of him. Of course that means that Bruce is famous. Everyone in the United States recognizes him. But it also means that for the rest of his life Bruce is going to have to wear that skuzzy hat with the fish scales on it. He’s going to have to wear the same shirt and the same pants. If he gets a haircut or changes anything, the tourists won’t recognize him. Which is why Bruce always wears his seatbelt. If his car should stop suddenly, he wants this face to stay just the way it was when Andy painted it. And then Bruce moves for the first time and looks toward the camera with a forced grin. That commercial beat 650 entries in 42 categories of advertising to take Best of Show at the 1988 Brodison Awards in Portland. Years later that 60-second video turned up at an art exhibition at a Maine college.

In 2006 Humble outlined a route to war by one of history’s better known trouble makers. It concluded with a reference that identified the subject as Hitler. Many thought the pressure from management was a reaction to this broadcast. Photo courtesy of Robert Skoglund In 2006 Humble outlined a route to war by one of history’s better known trouble makers. It concluded with a reference that identified the subject as Hitler. Many thought the pressure from management was a reaction to this broadcast. Photo courtesy of Robert Skoglund

|

Since making that commercial I've been able to call myself an award-winning humorist and, of course, I owe it all to Uncle Andy.”

Skoglund is a consummate story teller, not only in the Maine tradition, but in the longer history of the language. Asked if he was a St. George native he responded, “I live seven houses from where I was born and brought up. I live less than a mile from where my great-great-great-grandfather Samuel Gilchrest, who was one of the Insurgents fighting alongside of George Washington, is buried. I live five miles from where my ggggg grandfather, Moses Robinson, lived in 1734.”

His social and political observations and comments are very much in the Maine tradition. Community radio station WERU airs brief two-minute clips of Humble. They said a lot of people want them to have Humble do a show.

Skoglund does public speaking where he tells humorous stories – a version of the radio show without the music. In another example, a joke which Humble says in 30 years only a few anthropologists will be able to understand. The story is about Mr. Cobb, the rich Boston merchant, who made a fishing trip to Rangely every fall. One year Mr. Cobb arrived at the Rangely Hotel to find that his guide was sick, so he asked the hotelkeeper what to do. No problem. the best guide in Maine, Mr. Hoar, lived in Rangely, and he would be glad to take Mr. Cobb out on the lake. No one who saw the first meeting between these two great men will ever forget it. Mr. Cobb swaggered up to Mr. Hoar, held out his hand, and smirked. “Mr. Hoar, hah? I suppose you know what we do with Hoars in Boston.” And Mr. Hoar said, “No, I don’t, but I know what we do with Cobbs in Rangely.”

That Skoglund’s show was dropped by MPBN is not news to his many fans. Many loyal listeners and supporters made their feelings known to MPBN. Sara Hotchkiss, of Waldoboro, said, “I really miss the show. His music selections were 100 percent wonderful. The commentary was sometimes funny, sometimes thought provoking, and sometimes confusing, but I always came away with something to think about.”

His radio show was to many of its listeners, the most intelligent and entertaining program on public radio. John McKee of Brunswick described it as, “one of the best locally produced programs they ever had.” So why was he bumped? Two thought provoking items amid many others were particularly troublesome to MPBN.

One was Humble’s self described “rant” on war. In 2006 Humble outlined a route to war by one of history’s better known trouble makers. It concluded with a reference that identified the subject as Hitler. This first transgression was a series of events every high school freshmen has been taught. What listeners want to do with it from there is up to them, it would seem. The MPBN management feared they might not be the only ones drawing a parallel with the Bush administration’s evolution and Humble’s war rant. It was 2006, the Iraq war was expanding, opposition growing, and Iran was entering into the sights. Many thought the pressure from management was a reaction to this broadcast.

Regarding this broadcast and the reaction to it, Hotchkiss said, “If something is said in a way that is vague, or not totally finished, then people can put something they want into it. They can transform the meaning or the intent of comments left open ended in that way. MPBN wants listeners to be entertained or informed, but they don’t want them to think.”

The second incident, in a later program, was a letter he read from a Maryland fan who had written about taxes and education. The fan, a physicist from Virginia, noted that tax cuts often first come from the programs that serve the people who most need them.

Skoglund is a consummate story teller, not only in the Maine tradition, but in the longer history of the language. Photo courtesy of Robert Skoglund Skoglund is a consummate story teller, not only in the Maine tradition, but in the longer history of the language. Photo courtesy of Robert Skoglund

|

Humble titled the letter “Rant #8”:

“Dear Humble, We live near DC and ‘tax cut’ never means better control of pork barrel spending or programs that benefit corporations at the expense of everyman. It always means that the cuts will be in social services, humanitarian efforts, environmental issues, and all those ‘useless’ programs that generally benefit the poor and middle class and not the wealthy. A tax ‘ceiling’ was implemented on spending in nearby Prince George’s County. The result – PG County is now one of the worst counties in the nation in terms of student achievement, even though it has had a huge influx of higher paid residents. The folks who can afford it, even the minority residents, are sending their kids to private schools. Teachers have to buy their own supplies, books arrive three weeks after school starts because the school system’s expenditures are slow. Fiscal responsibility is one thing. Tax cuts designed to ‘red tape’ needy programs to death while expediting tax cuts to the wealthy (described as ‘beneficial to the economy’) are another.”

But, said Skoglund, “This letter was cut from the program by manager, Rich Tosier, before it aired.” Phew!! That was close, to think there might have been children listening.

Disappointed, long-time Kenne- bunk fan Skorapa said, “I don’t think MPBN has the right to censor artists. MPBN complained he made political statements during entertainment night. That was a contrived effort to get at him. If it’s public radio, then its part of what we want to hear.”

But Skoglund says he’s not about the politics, he’s about the humor. That is not to say that politics can’t be humorous, and at least as often, ridiculous. Humble’s humor is the kind of stuff that can make you laugh an hour after you hear it. On the program, the interconnectedness of his humor, comments on diverse topics, the music played, and his timing are what made his show so interesting. It’s a thinking person’s program, without saying or implying so. It was common sense, not something aloof.

Skoglund was asked a while back to write something for the Alumni Review at the University of Rochester, in Rochester, N.Y., from which he earned a graduate degree in 1970 in linguistics, the study of human communication. The following is an excerpt from what he published in the Alunmi Review.

“Should you take the time to sit before a mike for one hour every week and carry on a thoughtful one-sided conversation with a good friend, yours would be a welcome, appreciated voice. Do remember – your friend is in a car, in bed, working in a shop, or enjoying a meal. This is an intimate one-on-one conversation between you and your one close friend who is listening.”

If The Humble Farmer radio show can be categorized it would have to be as art/linguistics. What Garrison Keillor is to the Midwest and the nation, Robert Skoglund is to Maine and New England. To comparisons with the political comments of Prarie Home Companion’s Garrison Keillor, which is aired by MPBN, Skorapa said Keillor was not as sophisticated as Skoglund. While Keillor was doing the same simple thing over and over, Skoglund was always new, more complex and interesting.

Whatever the reasons MPBN managers went to the lengths they did to get Humble’s commentary off the air, it was definitely not the budget-busting price paid for the The Humble Farmer program. Skoglund was a volunteer who did the show for practically nothing for 28 years. Public service, with laughs.

Requests for an interview with MPBN manager Charles Beck for this article were referred to his assistant, Dave Morris. Morris said Skoglund had in the past signed an agreement that all volunteers sign regarding what their program will be. He was asked to sign a second revised statement more recently in which he would agree to do only what the show was designated as, in this case, play music. No commentary, etc. He did not sign.

Reviving the adage, “You can’t keep a good man down,” Skoglund is now producing a television show on community television in Maine. He also does a Humble Farmer radio show during the winter in Florida.

The circumstances surrounding the ouster of such a popular program producer has many people to question the goals, politics, and agenda of the management at Maine Public Radio Network. Maine Public Broadcast- ing is not the same as National Public Radio or the Public Broadcasting Service. Questions such as who is the “Public” in public broadcasting. How did the board members become board members? In what ways is public broadcasting serving the private sector? Questions The Humble Farmer would probably like to roll into one of his shows.

|